India has long been known as a country where milk and curd flow unbridled. Though it continues to hold a numero uno position in milk production, changing economic and social paradigms are forcing people to shift towards meat. No wonder then that India, where eating beef is a sensitive issue, has become the biggest beef exporter in the world. The country has traditionally been a mixed farming economy with agriculture and livestock playing complementary roles. It has been acknowledged that livestock sector makes important contribution to food security and poverty reduction.

Animals are not only used for ploughing and draught, but their dung goes back to fields as manure or is used for cooking. Similarly, agricultural waste is the biggest food source for animals. Livestock are also the essential safety net during times of crisis, acting as asset or collateral for credit. A major social role of livestock is as gender equaliser since the sector generates maximum earning opportunities for women.

However, challenges to sector increasingly been seen with changing socio-economic conditions. While Operation Flood and cooperative dairy movement focussed on small producers and took livestock sector to dizzying heights, rise in meat consumption and development of export markets are now shifting focus to larger set ups. This not only widens the social divide and leads to scarcity of natural resources but also lead to increase in outbreak of animal-related human diseases like swine flu.

Shortage of feed and fodder, loss of traditional cattle breeds, inadequate infrastructure and contribution to global warming are some of the concerns facing livestock sector.

Livestock of India

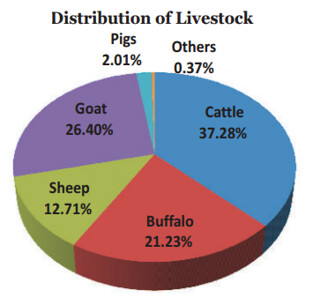

At the global level, livestock contributes 15 per cent of total food energy and 25 per cent dietary protein (2009 FAO report). With only 2.29 per cent of the land area of the world, India is maintaining about 10.71 per cent of the world’s livestock.

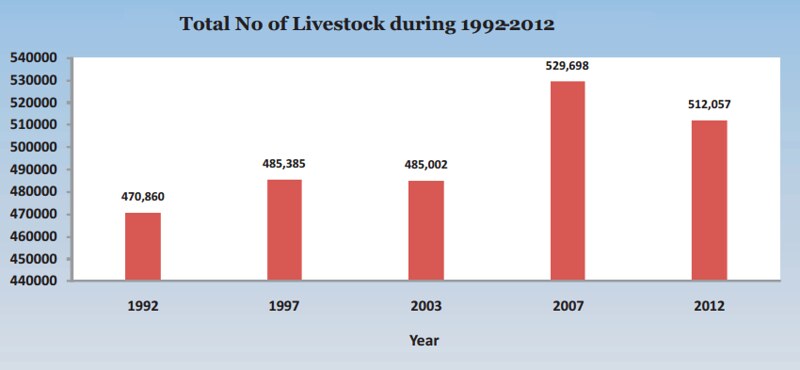

The livestock sector contributed 4.11 per cent to the national GDP during 2012-13. According to latest livestock census, the total animal population was 512.05 million numbers

in 2012 which means, there is a cattle and a donkey for every second human being in India. However, this is a drop of around 3.33 per cent over the previous census done in 2007. Fortunately, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Assam, Punjab, Bihar, Sikkim, Meghalaya, and Chhattisgarh have shown an increase in their total livestock population.

The number of milch animals, cows and buffaloes, increased from 111.09 million to 118.59 million, an increase of 6.75 per cent. On the other hand, population of sheep, goat and pigs registered a decline. The total poultry population saw an increase of 12.39 per cent.

Livestock production models

Data released by FAO shows that in a sample of 14 countries, 60 per cent of the rural households keep livestock. There are three kinds of livestock production systems in the world. Grazing system occupies 26 per cent of the earth's ice-free land surface and involves grazing on communal or open access areas in a mobile fashion. Mixed farming system has cropping and livestock rearing complimenting each other. In this over 10 per cent of the dry matter fed to animals comes from crop byproducts and residue.

Industrial system, generally described as modern, is characterised by large scale operations with intensive use of inputs, technology, capital and increased specialisation of production units. These systems are also described as "landless" because the animals are physically separated from the land that supports them. In India, the modern industrial system is gradually replacing the mixed farming system. So the livestock sector is changing from being multi-functional to commodity specific. There is a decline in the importance of traditionally important livestock functions such as provision of draught power and manure.

How big is big

In India, milk and dairy products are predominant culturally acceptable animal protein source. Although meat consumption is increasing, especially among younger, more cosmopolitan Indians, millions still remain vegetarian. According to National Sample Survey Organisation data, milk and its products rank second to cereals in the consumption of food items in both rural and urban areas.

India became the world's largest milk producer by increasing production from cattle and buffalo by four times between 1963 and 2003. Production was 132.4 million tonnes during 2012-13 as compared to 55.7 million tonnes in 1991-92.

India became the world's largest milk producer by increasing production from cattle and buffalo by four times between 1963 and 2003. Production was 132.4 million tonnes during 2012-13 as compared to 55.7 million tonnes in 1991-92.

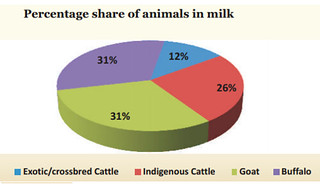

Buffalo, the heftier, darker counter to a cow, has largely been responsible for the phenomenal growth of country’s dairy sector. They are well-adapted to tropical climes unlike high-yielding cows. Across the country, more than half of all milk produced is through buffaloes. Cross bred cattle numbers are increasing but still account for just 22 per cent of the total cattle population.

The sector has received significant financial and political support for over 50 years. Though it was a priority sector in the very first five year plan, Operation Flood launched in 1970 made the real big contribution to India’s dairy sector. What spurred Operation Flood was a cooperative movement that went on to become world's largest milk producer.

Amul and Operation Flood

The Anand Milk Federation Union Limited, popularly known as AMUL, was formed in 1946, and is jointly owned by 3 million milk producers of Gujarat. It was response of marginal milk producers against exploitative trade practices of a big dairy firm and its agents who paid them low prices. Several cooperatives were set up at village levels which helped decentralise milk collection. The structure of Amul is such that village-level cooperatives are affiliated to a milk union at the district level which in turn is part of a state-level milk federation. Milk collection done at the village level is procurement and processed by district union and marketed by the state federation. Operation Flood of the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) replicated this structure all over the country.

The programme was designed to make use of the dairy aid offered by the European Economic Community and thus invited strident criticism initially from several quarters. The main contention was that the liberal foreign monetary assistance would cause milk prices to crash, dis-incentivise production and ultimately make India permanently dependent on other countries for its needs of dairy products.

However, the programme turned out to be a tremendous success. The market supplies were unaffected, farmers got the right prices, and necessary infrastructure was established and streamlined to match the growing urban demand. It was proved that an investment of Rs 20 billion over 20 years can increase milk production by 40 million metric tonnes. The success of this model also made dairy sector largest self-sustainable rural employment generator.

With better economic conditions, the demand for milk has also risen which is why the entire production is consumed within the country. The amount of milk produced in the country easily met the demand till 2006-07. A 4 per cent growth rate in milk production, double the growth rate of the world was good enough because the demand was almost as much as the supply.

However, now shortage of milk is increasingly being felt as even a meagre shift of milk to butter and cheese is creating difficulty. One of the reasons for shortage is large scale export of caesin or milk protein to US. Used for confectionary products, casein production leads to wastage of a vast quantity of milk. According to estimates of NDDB, the demand of milk may go upto 210 million tonne in 2021-22. To meet this requirement, production needs to increase by 6 million tonne every year.

Livestock cross breeding

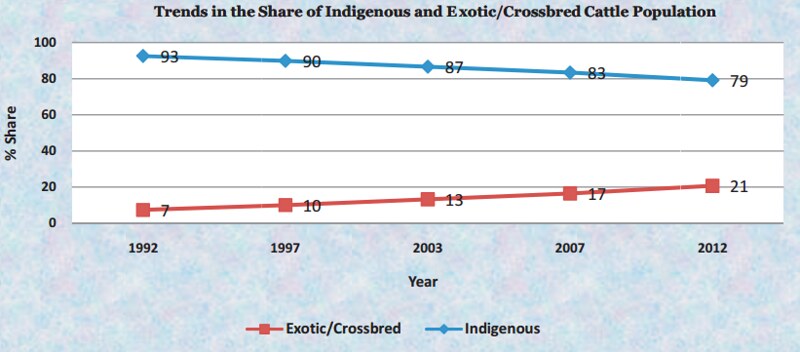

Improvement of cattle breed was one of the focus areas of Operation Flood. While benefits of this initiative were for everyone to see, the consequences remained underreported. As per FAO, 56 per cent of the dairy production growth in India can be accounted for by the increased number of milking animals and 37 per cent by the higher productivity of the crossbred animals. In 1982, fewer than 5 per cent animals in the Indian dairy were crossbred. By 2012, the share rose to 21 per cent.

Foreign breeds like Jersey and Fresian Holstein were introduced in India in 1970s. There was a blanket recommendation to cross-breed cows with foreign species which led to the Indian hardy species disappearing. However, there was no extension programme to advice which area they would do well in. Milk producers bought crossbred cows even in areas where resources were scarce and extreme climatic changes were observed. For instance, in Orissa, people took up cross-bred cows but the fodder of paddy straw was so less that it could not meet dietary requirements of cross-bred animals.

Indigenous breeds, known for withstanding harsh climates, smaller diet and lower incidence of diseases, were systematically destroyed. Hybridisation led to their characteristics disappearing. Fortunately, hybrid animals could not penetrate the whole of countryside. The National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) is now working on a breeding policy to explore cross-breeding within traditional breeds. A breed improvement programme on Rathi and Kankrej cows in Rajasthan and Gujarat is going on.

How’s the leg piece rising

When it comes to global meat supplies, China holds the dominating position. Around half of pork, which accounts for over 40 per cent of global meat supplies, comes from China. The country also dominates the poultry market, which makes up 26 per cent of the global meat supplies. Though India has doubled its meat production between 1980 and 2007, its overall output remains low in the global context.

Total meat production from cattle, buffalo, sheep, goat, pig and poultry at the all India level increased from 1.5 million tonnes in 2000-01 to an estimated 4.83 million tonnes in 2010-11. With growing urbanisation and increasing quality consciousness, the market for scientifically produced meat is expected to grow rapidly. The market is growing for ready-to-eat and semi-processed products because of a changing socio-economic scenario and an upsurge in exports, especially to the Middle East.

In 2012-13, India earned Rs 21,000 crore from meat exports to the US, Europe, Middle East and south-east Asian countries. It also became the biggest beef exporter in the world, beating Brazil. It exported 1.89 million tonnes of beef, a 50 per cent increase over five years ago. Indian poultry sector has been growing at around 8-10 per cent annually over the last decade with broiler meat volumes growing at more than 10 per cent, while table egg is growing at 5-6 per cent thanks to higher domestic consumption. Farmers in the country have moved from rearing country birds to hybrids thus increasing poultry meat production from less than one million tonne in 2000 to 3.4 million tonnes in 2012, says rating agency ICRA.

Poultry sector also provides an affordable alternative for meeting protein requirements as the prices of poultry meat has grown by 12 per cent over 2008-2013 as against 21 per cent for overall meat products basket. Growth in fishery sub-sector is next only to poultry. The policy for fishery development emphasises inland fisheries, particularly aquaculture in recent years, which has been instrumental in increasing production and enhancing exports. The total fish production during 2010-11 was at 8.29 million tonnes with a contribution of 5.07 million tonnes from the inland sector and 3.22 million tonnes from the marine sector. This was 5.54 per cent of the global fish production.

The challenges

The major challenges before us in livestock sector are genetic improvement in bovines, effective control of animal diseases, shortage of feed and fodder, inadequate infrastructure and inadequate dissemination of technology, skills and quality services to farmers.

Feed constitutes concentrates (wheat bran, oil-cakes etc), dry fodder and green fodder. Though we have a big dairy sector, the area dedicated to fodder cultivation has remained constant at 4.7 per cent of the total cultivable land since independence. Of this area, 10 per cent is in Punjab, which is also the major producer of dry fodder. However, now Punjab’s farmers are resorting to post harvest straw burning to save on labour cost. Farmers are also increasingly moving from cereals to cash crops which give less fodder resulting in higher fodder prices.

dairy sector, the area dedicated to fodder cultivation has remained constant at 4.7 per cent of the total cultivable land since independence. Of this area, 10 per cent is in Punjab, which is also the major producer of dry fodder. However, now Punjab’s farmers are resorting to post harvest straw burning to save on labour cost. Farmers are also increasingly moving from cereals to cash crops which give less fodder resulting in higher fodder prices.

The present shortage of feed and fodder in the country is as much as 40 per cent. According to IGFRI’s estimates, by 2020, India will require 850 million tonne of green fodder, 520 million tonne of dry fodder (edible crop residue) and 90 million tonne concentrates. Weakening traditional institutions and increasing land pressure have also threatened the natural grazing lands. Traditional coping mechanisms tend to fail in these situations and pastoralists are abandoning livestock production, voluntarily or involuntarily, in increasing numbers.

Climate variations like increasing temperature and decreasing rainfall are reducing the yield of pastures leading to overgrazing and degradation. In addition, climate change appears to be making arid and semi-arid areas even drier and extreme weather events like drought and flood more common. Changing land use patterns, especially that of common and traditionally pasture lands, is diverting a significant amount of the grazing pressure to forests.

The National Forestry Action Programme (NFAP) estimates that around 60 per cent of the livestock (about 270 million) graze in forests while the carrying capacity is only 30 million. Not only the allocation for development of feed and fodder is low, fodder seeds are also given low priority as compared to food crops. In the 11th five year plan, Rs 4903 crores were allocated for Animal Husbandry Department. Out of this, only 2.88 per cent was allocated for feed and fodder. Most direct impact of fodder shortage has been on milk production. With increasing fodder prices, combined with 4-6 per cent incentive on the export of buffalo meat, there are speculations of livestock keepers moving from milk to meat.

High prevalence of various animal diseases like Foot & Mouth Disease (FMD), Pestedes Petits Ruminants (PPR), Brucellosis, Classical Swine Fever and Avian Influenza is a serious impediment to growth in the livestock sector. Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) alone leads to economic losses of more than Rs. 20,000 crore per annum (NCAP, Preliminary Report 2010). Growing international trade in livestock and livestock products and this increased concentration in close proximity to large human populations have increased the risk of animal disease outbreaks and the emergence of new animal related human-health threats like swine flu and bird flu. Most of these losses can be prevented through timely immunization. India has a total of 8,732 veterinary hospitals and polyclinics and 18,830 veterinary dispensaries against the requirement of about 67,000 institutions. Most of these have poor infrastructure and equipment.

Livestock production also comes at an environmental cost. Though the sector contributes less than 2 per cent of global GDP, it produces 18 per cent of the global greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, the increasing geographic concentration of livestock production means that the manure produced by animals often exceeds the absorption capacity of the local area resulting in pollution.

The Planning Commission also cites lack of credit for livestock farmers as a limiting factor for its growth. The main challenges facing the fisheries sector include shortage of quality fish seeds, lack of resource-specific fishing vessels, reliable data, inadequate awareness about nutritional and economic benefits of fish and absence of standardisation and branding of fish products.

The way forward

To address these challenges, the National Livestock Mission was launched during the 12th Plan with the main objective of achieving sustainable development and growth of livestock sector by providing greater flexibility to the states. The Centre has released Rs 45 crore to five states under the Accelerated Fodder Development Programme which aims at enhancing availability of green and dry fodder and also mitigating fodder shortage caused by natural calamities such as drought and floods.

The forest department can also play a major role in augmenting fodder production in the country. The degraded forest areas can be used for assisting growth of indigenous fodder varieties of grasses, legumes, and trees under the village-level joint forest management committees.

Vast tract of unused lands along roadsides and railway track may be given on lease for a specified period for fodder production. Forest fringes are another important source to augment feed basket. Small-scale farmers typically face higher transaction cost than large-scale enterprises. It is more difficult and costly for them to access higher quality inputs (especially feed), credit and technology. This high transaction cost can be reduced through collective action group lik e a cooperative. This way, smallholders can be incorporated into high value supply chains from which they would otherwise be excluded. The Central government has now started giving subsidy to entrepreneurs for fodder block making units to address the problem of transportation from surplus to deficit areas.

e a cooperative. This way, smallholders can be incorporated into high value supply chains from which they would otherwise be excluded. The Central government has now started giving subsidy to entrepreneurs for fodder block making units to address the problem of transportation from surplus to deficit areas.

The Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries has initiated National Programmes for prevention and control of FMD, PPR and Brucellosis. The FMD control programme has been expanded to 221 districts and will be expanded to cover the entire country in a phased manner. Similar programmes have been initiated to control PPR and Brucellosis.

For fisheries, schemes of integrated approach for enhancing production with forward and backward linkages right from production chain and input requirements like quality fish seeds and feeds besides value addition and marketing of fish are required. Cooperative sectors, village self-help groups and youths can be actively involved in intensive aquaculture activities.