The global crisis due to Covid-19 has hit India after coursing through western Europe. India’s response to curtail the spread of the disease was quite decisive. It announced a Janata curfew on March 22, followed by a complete national lockdown from the midnight of March 24. This, however, exposed the fault lines in our system: thousands of migrant workers got stuck at various places, especially in metro cities, as they could not get enough time to plan their return. Providing them basic support like ration and shelter became a herculean task for the establishment.

The migrant workers in different locations in Delhi, Mumbai, Surat and other cities are expressing their desire to return to their native places. Along with the disease itself, the migrant workers’ plight remains a national concern. A recent submission made to the Supreme Court of India by the central government reveals that there are about 41.4 million migrant workers in the country during the lockdown and more than 2.5 million are living in relief camps and shelters. In terms of sheer numbers, the size of the migrant workers is equivalent to the population of Spain, one of the worst affected countries under Covid-19.

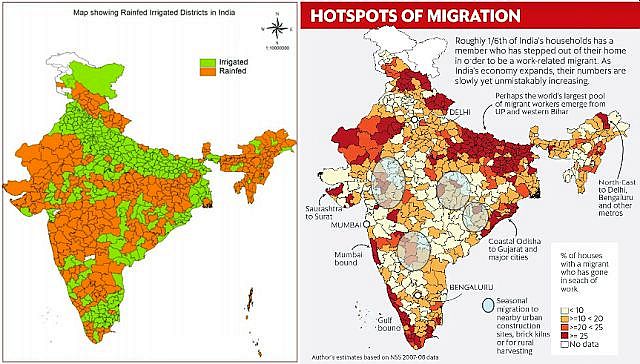

A close look at the source of these migrant workers suggests that majority of them go in search of jobs from regions where agriculture is mainly practiced under rainfed conditions. A district having less than 40 percent of its total cropped area under irrigation is defined as rainfed.

These pockets incidentally are also the poverty zones of India inhabited by huge number of farming communities who own very small landholdings, generally scattered in different patches.

We try to analyse the options small and marginal farmers and policy makers hold in the immediate and short term future.

Click here and here for source

Rainfed, small holding and migration nexus

About 56 percent of India’s workforce works in agriculture and allied activities, even though its contribution to India’s gross domestic product (GDP) is only about 13 percent. Further, in rural India, 70 percent of the population is dependent on agriculture and allied activities as the main source of income.

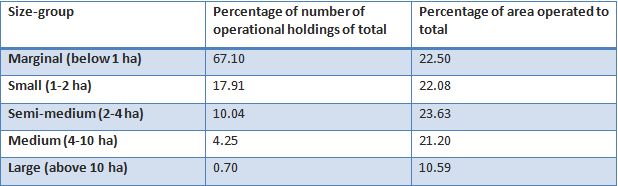

Analysis of farmers’ landholding pattern suggests that small and marginal farmers constitute 85 percent of the farming community (owning less than 2 hectares of land) but own only 44.58 percent of the farm operated area.

The rainfed region of India typically faces the challenges of imperfect markets for inputs, which results in product leading to smaller value on return to farming; absence of easy access to credit leading to suboptimal investment decisions and input applications; poor human resource base; limited access to suitable extension services restricting suitable technological know-how; poor access to ‘public goods’ such as public irrigation, command area development, electricity grids etc. All these factors contribute towards large number of people from the region migrating to cities for alternative income.

More person power available but more people to feed

Assuming that about 75 percent of the 41 million migrant workers stuck in different places will return to about 300 rainfed districts, in an average each district will witness approximately 100,000 people returning before the kharif season. This will mean the households will have more helping hands in agricultural fields (not necessarily skilled one) but also more people to feed.

Back to the basics: Ensure household level food and nutritional security first

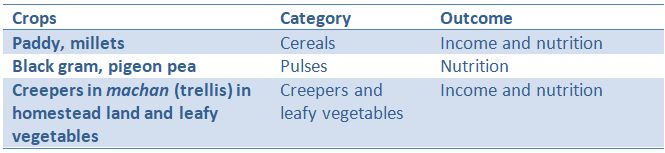

With some sort of local level lockdown continuing and many people not ready to move out yet for job outside again, an average farming family needs to revise its strategy around food security. With local markets and nearby agriculture produce market (APM) still unsettled, it will be advisable that the small and marginal farmers opt for crops which will ensure food and nutrition security during this kharif season. A possible package of practice could be:

Seeds and manures can be given to all small and marginal framers as one-time grant or seed capital, especially for food crops and directly consumable cash crops.

Diversify the livelihoods basket

Typically, a farming household’s livelihood depends on agriculture and allied activities, supplemented by some non-farm interventions. The farmers should try to diversify the livelihoods basket by engaging in income generating activities around non timber forest produce (NTFP), especially in tribal areas. Some state governments like Maharashtra have already brought NTFPs under essential commodity list.

The local self-help groups (SHGs) may collect NTFPs like mahua and tendu leaves and these can be connected with the central government’s Van Dhan Scheme for forward market linkages. The people who return with some cash but lack in farming skill can go for rearing livestock and fisheries.

Big push for MGNREGS

Many migrant workers will return to villages and may not have the skills in farming. They need to be engaged meaningfully to create local level assets around natural resources. To mitigate the lack of cash for existing farmers as well as the returnees, a bigger push to Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) will be very helpful.

Many migrant workers will return to villages and may not have the skills in farming. They need to be engaged meaningfully to create local level assets around natural resources. To mitigate the lack of cash for existing farmers as well as the returnees, a bigger push to Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) will be very helpful.

The central government has increased the wage rate recently under MGNREGA, but more number of people needs to be brought under this. It’s high time to increase the number of persondays from 100 to ensure sustained income in the rural areas.

Working Capital/Vulnerability Reduction Fund/ Community Investment Support Fund

It is imperative that during this kharif season the farmers will need working capital. For this, credit has to be arranged in manner wherein the farmers will have confidence for going for crop planning. Currently there is provision of parking funds at the community institution level under National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM). This provision can further be enhanced and expanded to all the villages through appropriate local mechanism so that the community collectively can cope with any emergent situation.

Skills enhancement

This pandemic has undoubtedly demonstrated the value of technology in an unprecedented manner. This happened in villagers getting messages on Covid-19 from various agencies and other measures. In a few rare cases, the migrant workers even tagged their local political representatives about their plights and locations.

This pandemic has undoubtedly demonstrated the value of technology in an unprecedented manner. This happened in villagers getting messages on Covid-19 from various agencies and other measures. In a few rare cases, the migrant workers even tagged their local political representatives about their plights and locations.

It’s important that farmers now master the digital world for good and soon. It will do a world of good if the farmers and potential migrants learn how to access services and information; how to use internet banking etc., through digital technology along with enhancing professional knowhow on their skill verticals like plumbing, construction, carpentry, etc.

Local institutions coming together

In rural areas, the farming community is intertwined with various institutions. There are Gram Panchayat (equivalent body in scheduled areas), primary agricultural credit society (PACS), self-help groups (SHGs), SHG federations, farmers’ producer company (FPO), farmers’ club, and the district administration. This crisis gives ample opportunity for all these institutions to come together and formulate a revival plan for each district starting from the village level.

Conclusion

During the last decade, there have been ambitious policy declarations in regards to Indian agriculture, especially related to rainfed regions. Two such big ticket ideas are ‘Bringing Second Green Revolution’ in the largely unrealized rainfed region and the other is ‘Doubling Farmers’ Income’. With basic institutional structure (market, credit, insurance, research, extension service, etc.) not in place, all these announcements unfortunately remain unrealized, nicely placed policy documents.

When all over the globe, we are now talking about restarting life in view of Covid-19 pandemic, its high time we pause and rethink realistically about how to revitalize agriculture sustainably in this hinterland of India. Because it’s most apt now to say "Everything else can wait, but not agriculture".

Biswanath Sinha is with the Tata Trusts, Mumbai. Kuntal Mukherjee is with Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN), Raipur. Views expressed here are personal and all images belong to the authors.