Springs are important, and so it is important to get the nature of springs clear at the outset. A spring-simply put- is that point or area at which water emerges from an aquifer located underneath the ground onto the surface.

Types of springs:This emergence can be due to several reasons like, change in slope, change or nature of local geology or geologic structure. Springs are classified into different types by the nature of their origin. Thus springs can be classified as per the following:

- Depression: Formed when water table reaches the surface due to topographic undulations.

- Contact: Formed at places where relatively permeable rocks overlie rocks of low permeability.

- Fracture: Occur due to existence of jointed or permeable fracture zones in low permeability rocks.

- Fault: An impermeable rock unit may be brought in contact with an unconfined aquifer due to faulting. Groundwater (at depth) under hydrostatic pressure (such as in confined aquifers) can move up along such faults.

- Karst: Large quantities of water move through the cavities, channels, conduits and other openings developed in limestones.

Geographical extent: It is usual to associate springs with the mountains. It is true that mountain topography is more conducive to the emergence of springs. The Himalayas, the Eastern, and Western Ghats have a rich treasure trove of springs which give birth to several rivers. The great Krishna and Godavari rivers, along with all the other perennial rivers of the Indian Peninsula owe their origin to springs. However, springs are to be found across all of India to varying extents, including in the vast flatness of the Gangetic plains. Naimis Aranya, in the watershed of the Gomti, owes its existence to thousands of bubbling springs that have given rise to a mythology of their own. Villages in the peninsular state of Andhra Pradesh also depend on springs.

Extent of use: While it is true that with more than a million pumps India is a vast pumping machine, this does not even begin to tell us of the extent of the groundwater use of the country. People in all mountain areas almost entirely dependent on springs. The reason for this is the topography. Mountain areas cannot boast of the extensive aquifers that are found in the Gangetic plains or in other relatively flat areas. Instead, they depend on local or what are ofter called as 'perched' aquifers-small and isolated pockets of water found where the geology forms a convenient receptacle for water. These are often fed by fissures and faults in the rocks that bring water from far away. The small size and the nature of these aquifers rules of the fact of making wells for extracting groundwater - not only that, blasting and drilling may well close the fissures that bring in water and possibly the spring itself. And so, mountain peoples have learnt to content themselves with the water that is issued naturally from the springs. This is used for drinking, washing and irrigation- infact, for every conceivable use.

Traditional knowledge/lore: With the importance of springs, it is not surprising that there is a substantial body of traditional knowledge around their use and management. Springs are often demarcated by temples and small stone sculptures such as the 'gomukh' to be found in the western ghats. These are stone spouts shaped like the head of a cow or some other animal and placed so that the water issues from the mouth of the sculpture. This is mainly found at the springs that form the source of a river. In the Himalayas, a structure like a miniature step-well (called a naula) is constructed which allows seepage while also providing a certain amount of storage and protection.

These structures and the many others like them are governed by strict rules to protect agains pollution. This includes a ban on washing and bathing at the naula, a ban on entering while wearing footwear etc. The flip side of course, is that these codes of conduct often also foster caste distinctions. In the Central Himalayas atleast, naulas are – besides marriage- the last bastions of casteism.

In Sikkim, traditional knowledge and beliefs provide a strong force towards the preservation of the springs. Springs are believed to come out where Goddess (Devithan) dwells and are important places of worship. These cultural beliefs also prevent polluting these sources and are instrumental in keeping biological contaminants away to a large extent.

Current status: While individual organizations are beginning to maintain a database of springs in the areas they are based, there is still no exhaustive census of the total number of springs in the country. However, there is some recurring anecdotal evidence across the country that dependence on springs as either the primary or the secondary source of water for domestic use is increasing while simultaneously, the yields of these springs are decreasing. Springs continue to be extensively used for domestic water supply. In most cases, the springs are untapped and nearby households collect water directly from the spring. Springs with a large discharge are harvested to supply piped water. Most villages, such as Indwalgaon, boast a hybrid system which uses a centralised water supply for the village in conjunction with smaller springs used by hamlets.

Crises: There is a decrease in both the quantity and quality of the water available from springs. This, coupled with increasing population- both resident and tourist- translates into water scarcity and much hardship for rural families.

Sinking of multiple borewells and extensive pumping is the single biggest threat to springs in the Eastern and Western Ghats, as well as elsewhere where springs are prevalent. Both drilling and pumping change the nature of the aquifers as well as the level of water in them. This causes a decrease in the time for which springs flow, the amount of water flowing in them, and also whether the springs continue to flow at all.

Catchment areas of the springs are being threatened by changes in land use, pollution and activities such as the construction of roads and dams. A spring is fed by the water that percolates down into the aquifer that it emerges from. The amount of water that percolates into a given area and for a certain amount of rainfall depends on the nature of the land. Land covered by broad leaved forest will always arrests rainfall runoff and help water to percolate than if the land was paved over with concrete. Deforestation and construction are severely impacting the amount of water that percolates into the ground.

It is also essential that the conduits through which the springs are fed -most notably in the case of fracture and fault springs- be kept open. These can be closed or shifted by movement in the rocks which may occur due to an earthquake or due to blasting. The blasting of rocks for construction of dams and roads has led to several springs drying up in the mountain areas of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Sikkim.

Climate change has its own role to play in the decline of spring discharge. At present, anthropogenic changes predominantly impact groundwater . However, erratic rainfall directly impacts the recharge that is available to springs. Other indirect impacts are due to changes in cropping patterns and increase in extreme events.

Springs being extensively used for drinking, water quality concerns need to be taken seriously. Studies carried out in the Himalayas indicate that all springs in the vicinity of villages- those that are most used for drinking- are contaminated with faecal coliforms. This needs to be treated at source, by protecting the spring recharge areas and a program of awareness generation

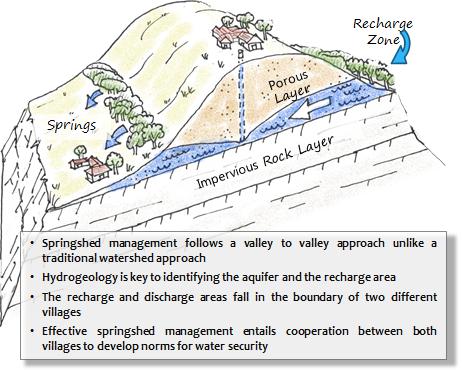

Work being done: The discrete nature of these springs means that they are intensely local. It follows that conservation and management of these springs also needs to be local. Recognising this, there is now a new movement to enable village communities to understand, protect and manage their own springs. Trials in this direction are being made in the Central Himalayas , the North Eastern Himalayas , and the Western Ghats among other regions. These pilots indicate the interest in learning about the invisible workings behind springs and the potential to develop a cadre of people who are conversant with their local geology and can develop informed strategies to manage their springs. The willingness of communities to set aside their differences and cooperate over the management of their water has also been demonstrated. The experiences so far have also contributed to the creation of a protocol for the management of springs at the local level .

It remains now to further the work already begun by empowering communities to manage their springs using both science and negotiation.

| Content developed with the support of: Dr. Jared Buono, a hydrogeologist working on springs,and Kaustubh Mahamuni, a hydrogeologist working with ACWADAM on springs |