Sixty eight percent of India's population lives in rural areas but when it comes to facilities -- including the availability of safe drinking water -- cities and towns corner most of them. Investments to rural India increased from Rs 31,356 crore (2002-07) to Rs 89,150 crore (2007-12) but this hasn't helped bridge the gap. While geographical and logistic difficulties remain major hindrances in reaching out to the nation's growing population, policy and institutional efficiency also leave much to be desired.

Even the norms set to supply domestic water underscore the preferential treatment meted out to urban areas. A daily supply of 40 litres per capita (lpcd) is considered the minimum requirement of people in rural areas, but the urban equivalent is 135 lpcd. The Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-17) has now set a goal of providing at least 50 percent of rural population with 55 lpcd.

Outsourced water

The difference seems more ironic since most of the water supply to cities comes from rural areas. Delhi, though located on the banks of the Yamuna, gets most of its water from the Bhakra Dam in Himachal Pradesh and Ramganga Dam in Uttarakhand. It could soon also get water from the Renuka lake, which is around 300 km away in Himachal Pradesh. Mumbai is almost completely dependent on a series of dams such as the Vaitarana, Tansa and Bhatsa in rural areas of Maharashtra.

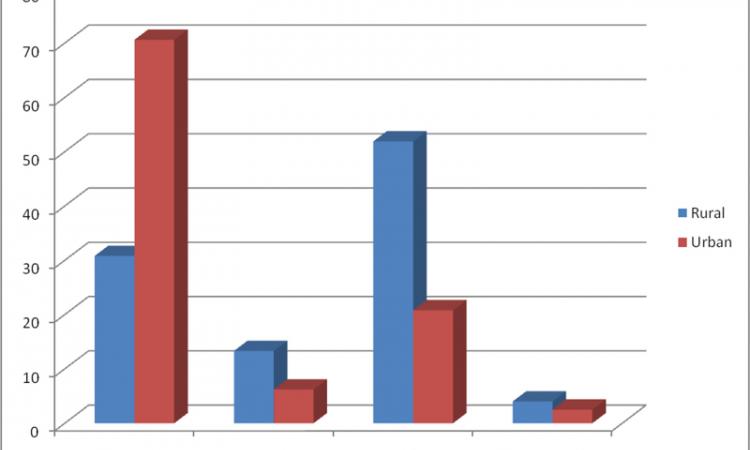

(Within the premises: Source was located within the premises of the household. Near the premises: Source was located within a range of 100 metres from the premises in urban areas and within a distance of 500 metres in rural areas. Away from the premises: Source was located beyond 100 metres from the premises in urban areas and beyond 500 metres in rural areas.)

Urbanised states score better

Urbanisation is termed as the percentage of state population living in cities and towns. States that are more urbanised than others have better drinking water facilities. In 2011, 22.1% of rural households got their drinking water from distant sources when compared to only 8.1% of urban households. There has been a sharp decline in the use of wells in the villages for two reasons:

- the usage of tap water and hand pumps have increased, and

- groundwater levels have decreased.

Also, only 1.5 percent of wells in rural India have covers on them. Uncovered wells make up 11.8 percent as compared to only 4.5 pecent in urban areas.

Exceptions to the rule: Kerala and Himachal Pradesh

The top eight urbanised states score above the national average of treated tap water supply except Kerala, which falls short. This is likely because of 4 reasons:

- most of its urban households are directly dependent on groundwater and have independent water connections from bore wells,

- the state government has taken fewer efforts in increasing the coverage of treated water in urban and rural Kerala,

- the state has been unable to use river water sources, and

- Kerala Water Authority (KWA) schemes are poorly planned particularly in the areas of source sustainability, technology choice and design optimisation resulting in source and system failures.

Conversely, the bottom eight urbanised states have lower coverage in treated tap water supply with Himachal Pradesh as the exception. In fact, Himachal Pradesh has the best coverage in treated tap water supply in all 28 states in 2011 probably because it is not only a hydrologically rich state but also has a better social setup and grant-based Central support for its plans.

High contamination and poor access to water testing

There are various examples of contamination from industry affecting rural water -- the Coca Cola bottling plant case in Plachimada (Kerala), the Raymond factory in Yavatmal, mining around Korba in Chhattisgarh and near Jharsuguda in Odisha. In addition, the last two decades have seen an increase in natural water contamination related to fluoride, arsenic, iron, nitrate, etc. The situation is more worrisome in rural India due to the lack of alternatives to this water -- almost 78,508 rural habitations are affected by fluoride and arsenic contamination.

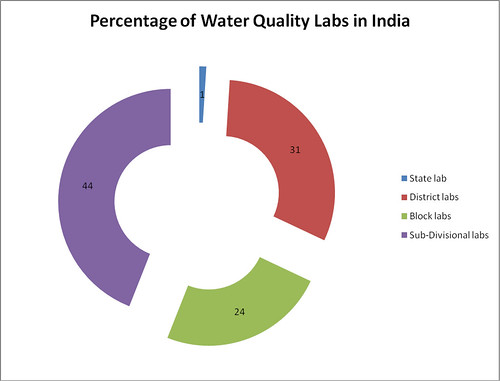

In 2010, an evaluation study of the Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission done in five states showed that 71 percent gram panchayats had no field testing kids at all. Also, 79 percent respondents said that their water sources had never been tested by technical personnel.

Current investments in rural water supply do not seem to be enough to address all the water problems that are being faced. In-village water supply schemes could possibly ensure better management and operations by the panchayats and the local communities.