Water consumption varies based on many factors – how much water is available, where one lives, one’s personal habits, the weather, the seasons and so on and so forth. Each of these contributes to varying usage patterns. A simplistic method of averaging out consumption and calculating the demand based on it is an overoptimistic and narrow approach to planning a city's water supply. However, till date, this remains one of the cornerstones of urban planning in India.

Questions such as the ones noted below need a re-think.

- From where does the water reach the city?

- How far away is the source?

- How much does this journey from the source cost?

- Is the water distributed judiciously? If it isn't, where and how is it lost?

- In what form is it flushed out of the system?

Bangalore, one of the fastest growing cities in the country, has expanded and become more crowded. The population density has increased by more than 25% in the last 40 years, with more people living in the peripheral areas than in the centre. The wastewater treatment capacity of the city does not meet the demand, which invariably leads to wastewater being dumped unceremoniously into rivers and lakes, ultimately polluting groundwater too. Groundwater levels fluctuate in proportion to development; the more the growth, the more is the groundwater overdraft.

This research paper argues that urban water planning needs a complete overhaul to face future challenges. What is needed is an understanding of the economical and ecological cost in using the resource, and the fact that water production & consumption, can and will change constantly.

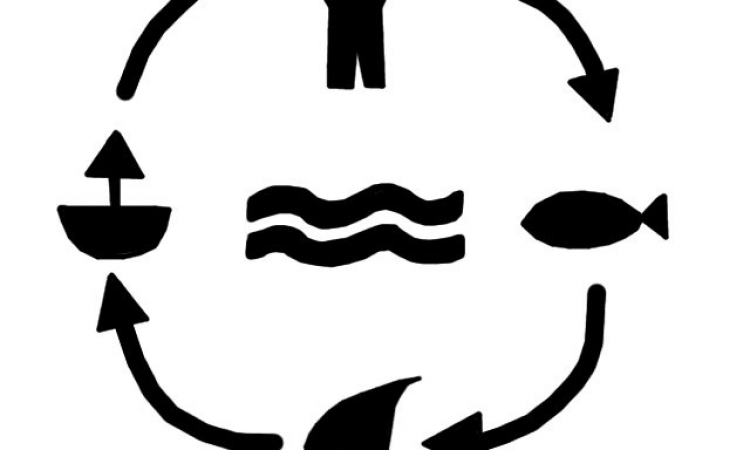

Thus, though there is a huge mismatch between high growth areas and available water, it is only when we link domestic water to society or the people it serves, can we get a fairer picture. For this what is proposed is a social metabolic framework - a reference plan that considers the social and environmental aspects of water, the water sources, wastewater disposal methods and how water usage is a variable.

To begin with, the water that flows into the city and the wastewater that is emptied out of it, must both be taken into account to calculate the water balance. Bangalore is already groundwater deficient, which means that more water has been withdrawn than can be replenished. An equation to calculate the water balance, which determines how much water has been used and how much is still left, has been explained in the paper. This will need further fine-tuning, which is possible by adding in data about the actual water demand as per ground conditions.

Other unknowns such as migration in the future, growth of the city as a global hub, etc. must also be added itno the model's variables. Spatial variation, which is how different areas across the city may have a different set of problems and related issues should also be taken into account. Water supply and sewerage must be tackled together, as part of a two-pronged approach to solving this problem.

Instead of simply concentrating on augmenting Bangalore’s increasing water needs, it is this social metabolic framework that can help planners work towards a more efficient and well-managed city.

This research paper ‘Social Ecology of Domestic Water Use in Bangalore’ published in the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), April 13, 2013 issue has been co authored by Vishal K Mehta and Eric Kemp-Benedict from the Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm; Rimi Goswami and Deepak Malghan from the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore and Sekhar Muddu who is with the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

The research underlying this paper was funded by the Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and is an integral part of the Bangalore Urban Metabolism Project (BUMP).

More information on it, you may view www.urbanmetabolism.in