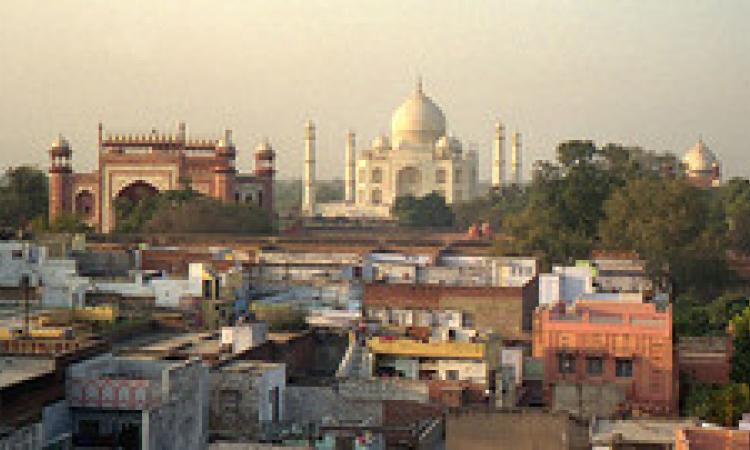

The Tajganj boasts a heritage walk taking sightseers back in time to the excellence of the Mughal era. History-loving eyes examine this threshold to the mausoleum for its remains from the urban landscape of the Mughal lay. What meets the tourist, and rather tragically, is the stench from the natural drain (now open sewage), narrow crowded lanes with houses encroaching upon any available inch of a space and broken roads with loose hanging electrical wires threaten the lives on the walkway everyday.

Tajganj has become an oxymoron to the wondrous beauty, architectural excellence, exceptional design and idyllic stature of the mausoleum it encircles. A slum no different from other city slums, it is a far cry from what it once was. Everyday problems of water, health and sanitation cloud its skies grey. Lack of infrastructure and administration, along with problems of urbanisation, population explosion and city-ward migration further thin the air it breathes.

A long time ago, the Tajganj proudly stood as an extension of the Taj Mahal itself. It shared the planned and detailed architecture and infrastructure that was symbolic of the Mughal era that included water supply and management at its core. It led to the creation of one of the world’s wonders, a riverfront garden, as a module of the riverfront city. It contained a Char Bagh with the main building on the terrace overlooking the river and water heritage in the form of well towers with Persian wheel system, aqueducts, water channels and cascades.

As part of culture, aesthetics, and recreation as well as climatic moderators, the Mughals had planned these water-oriented cosmoses integral to meaningful design and management. The city’s rich drew water from the riverine core along the riverfront, while the rest depended on groundwater. The water systems had a planned network of wells that were supported with drainage and ground water recharging systems. Tanks, wells, baolis (step-wells) and ponds ensured that the river or groundwater was never over-burdened.

The Tajganj, which came into establishment to house the artisans involved in construction of Taj Mahal, was lined with more than 70 wells that were either used for drinking or irrigation purposes. A natural drain, now called the ‘Taj East Drain”, carried the storm water and overflows directly in the Yamuna. The wells, tanks and baolis were built either by the Mughals or by the communities, but were managed by the communities in both cases. This cemented a thorough understanding of the available resources, nurtured life and culture, and facilitated agrarian development, trade and commerce.

The new ‘improvements’ in living with the infrastructure development by the state have largely been responsible for the ‘Sarkar Sab Karegi’ (State is responsible for all) attitude, taking away onus from the community and shifting it on to an ominous third party neither directly affected nor in contact with the situation. This has cost the Tajganj its water, hygiene, sanitation and health.

Fewer than 20 wells out of its original 70 wells are visible today. Most of them are dead, defunct, or filled and built upon. Potable drinking water means water from water tanks, borewells and a few functioning hand pumps in the community. With little laid infrastructure, sewage seeps into the underground water worsening the quality of available groundwater. Seeking out clean water has become a time and money consuming activity that few people can afford.

Frugal financial resources heavily strain the life in the slum with presumed ownership of water constantly threatening peaceful co-existence. Today, livelihoods of people here is in jeopardy. Most of the people are involved in various traditional livelihoods like marble carving/inlay, leather shoe making (cutting and sewing of shoes), zardozi, etc. but make only enough money to survive. Once as a bazaar or market Tajganj was the main street of the city, contributing financially to the maintenance of the Taj Mahal.

The vanished reverence for tradition and old lifestyles has dismantled the base of social life here. Life is an ongoing struggle exacerbated with poor quality living conditions worsened with poor health of the people. Cases of malaria, typhoid and gastrointestinal diseases are routine. Families end up spending a quarter to a third of their incomes on medication.

Restoring the water systems

To restore the quality of life, Centre for Urban and Regional Excellence (CURE) – a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) has been working in Tajganj by attempting to restore the water systems that once existed. Resource efficiency and self-reliance are keystones in its development trajectory. Working with the city administration and Municipal Corporation, they have laid out a plan to treat water and improve sanitation. It is mapping the entire region to incorporate rainwater harvesting and recharge in all public spaces and reviving old wells. It is redesigning existing houses to improve their water and sanitation situation and developing about 300 new houses with rainwater harvesting, proper sanitation and recharge systems. However, this is still work in progress as working with communities takes time.

Tajganj was not always short of water. It had enough water from the river Yamuna, wells, tanks, ponds and baolis. Supporting the entire system was a vision, one, which aimed at ensuring water supply for several decades at least, if not a century. Excellence in architecture – discreetly stamped by Taj Mahal – went hand in hand with excellence in an urban system.

People continue to live in this broken-down system and continue to do business in this ‘eyesore’ (as it is commonly referred to). Weakening of traditional management practices, lack of upkeep of structures and disuse has led to its deterioration. These systems had stood the test of time but things changed and people changed.

Only time will tell if the change was for better or worse.