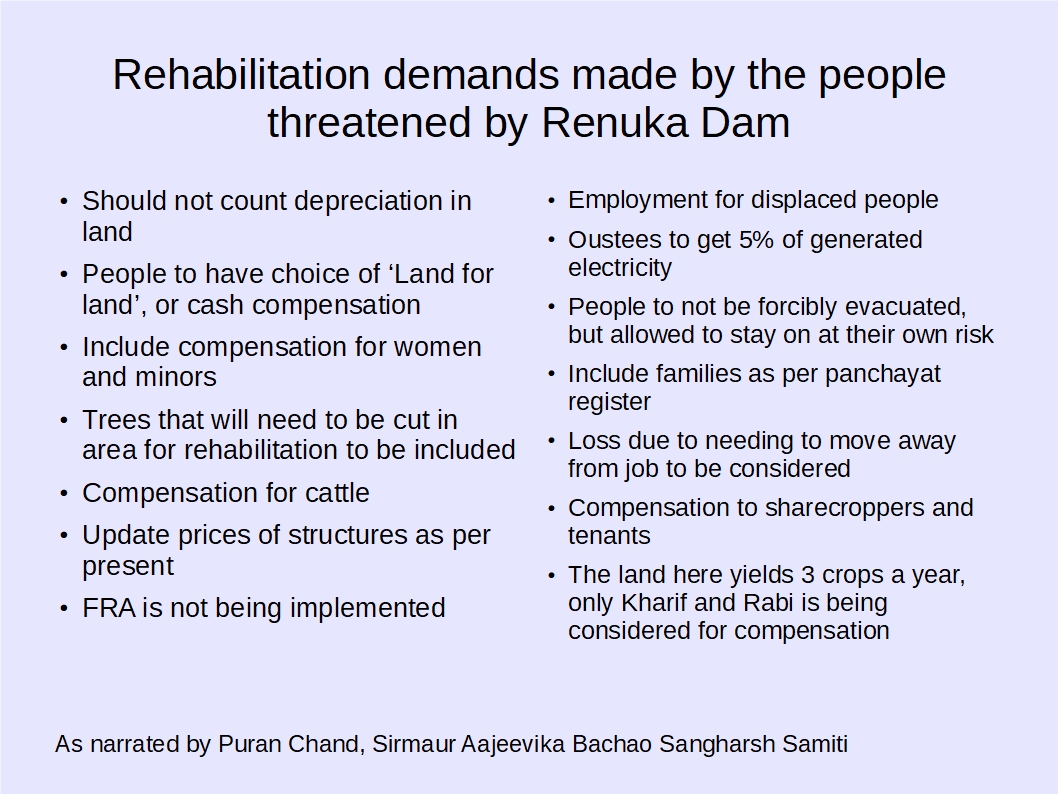

When I meet Puran Chand, an activist in the forefront of the anti-Renuka dam struggle, he dictates from the two much-thumbed pages of his notebook the several objections he has against the government’s plan for the rehabilitation of people displaced by the Renuka dam. Here is a man who has repeatedly raised his objections and perhaps tired of repeating it. And who can blame him?

The idea of a dam in the Renuka valley in the Sirmaur region in Himachal Pradesh started taking shape as early as the 1960s when it was proposed that the Giri river could be dammed to produce electricity. In order to make this project economically feasible, first, a flood-control component was tacked on and then the proposal to store water to be supplied in Delhi. In 1994, when the Memorandum of Understanding was signed, the project had taken on the form of a 148-m-high dam with a 24-kilometre-long reservoir. This dam has been contentious since then, with the affected villagers protesting the submergence of land, of its impact on wildlife, of the fragility of the site, and the lack of an options assessment.

People come together to oppose the move

Kuldeep Verma is the head of an organisation called People’s Action for People in Need (PAPN) that works on improving livelihoods in the Sirmaur district. In 2008, the organisation began working in a village called Mahthu which would be submerged by the proposed dam. It is there that Verma learned of the impact of this dam in his neighbourhood, especially of the loss of land and agriculture. Verma says, “At first sight, the money looks tempting. But once the land is sold and people have to move, then they are forced to enter the cash economy. At that point, the money runs out quickly. The people who move will not be assimilated into the community of the place they move to--they will never acquire traditional rights. This divides the community. Now the people who are the most vocal and powerful are those who want to sell, who never lived off the land and are not interested in making a quick profit.” In Verma’s experience, the rich and powerful people in the village have livelihood options that are not tied to the land, consequently, the idea of ready cash is more attractive than holding on to the land. On the other hand, the poor, due to a lack of education, do not have these options; loss of land is equated with loss of livelihood.

The organisation began to meet active leaders in the community and help mobilise the residents. They contacted Manshi Asher of Himdhara and organised an exposure visit to Tehri so that people could see the real impacts of a large dam instead of merely believing the government promises. Puran Chand has been at the forefront of this struggle with his colleagues since the 1990s. In the early years, they fought against the construction of the dam. But then the state invoked the “urgency” clause in the Land Acquisition Act, changing the stakes and forcing activists to focus on issues of rehabilitation.

What is the urgency clause?

The Section 17 of the original Land Acquisition Act of 1894, the urgency clause allows the government to immediately seize private land (and offer adequate compensation later) for any public work which is considered to be so urgent that even a little delay would cause damage. While the text of the law includes even educational institutions and affordable housing, the bulk of the text focuses on instances of floods and other natural disasters.

The spirit of this clause--that it needs to be invoked in emergencies--has been supported by the Supreme Court. In their ruling on a case in which the Delhi government had invoked the urgency clause to obtain land for an electric substation, the court says, “The degree of care required to be taken by the state is greater when the power of compulsory acquisition of private land is exercised by invoking the provisions like the one contained in Section 17 of the Act because that results in depriving the owner of his property without being afforded an opportunity of hearing.”

Sadly, that has not been the case here. Puran Chand has pointed out numerous discrepancies in the proceedings, alleging that the people who were taken to see the area proposed for rehabilitation were those with a strong pro-dam bias. In the meantime, the site of the dam, as well as its submergence area, has been marked out on the land.

Is it of national importance?

The Government of India has declared the project as of “national importance”. This proclamation influenced the National Green Tribunal’s decision to uphold the issued clearance while admitting that there were irregularities in the process. The reasons for this national importance are not clear. No assessment of alternatives has been done for the project despite options assessment being a crucial part of planning for a dam. This raises the question of whether Renuka dam is actually the only way by which Delhi can slake its thirst.

According to Kapil Mishra, the former water resource minister in Delhi, the city does not need water from the Renuka dam. Financial problems are also plaguing the project. A committee appointed by the National Green Tribunal recommended in 2016 that rehabilitation needs to be speedily implemented in view of the uncertainty the villagers are living with. This has not been done yet due to a shortage of funds. The rehabilitation process also does not take into account the rights of the sharecroppers and landless farmers. These rights are included in the people’s demands for proper rehabilitation.

Rather than waiting till the impasse is resolved, a few farmers have taken steps to ensure their livelihoods. Durga Ram, a resident of Mahthu, has taken up mushroom farming. “I wanted to find some farming that I could do without land,” he says as he surveys his ancestral farm slated to be submerged if the dam is constructed.