The Mandovi river is picture perfect. She is the wide, placid river fringed by the coconut palms and dotted by the boats that we think of when we think of Goa. For the Goans, the Mandovi is a lifeline as she provides drinking water and fish. She also waters the rice crop that they live on and serves as transport--cargo ranging from iron ore to coconuts are carried down the river on boats of varying sizes.

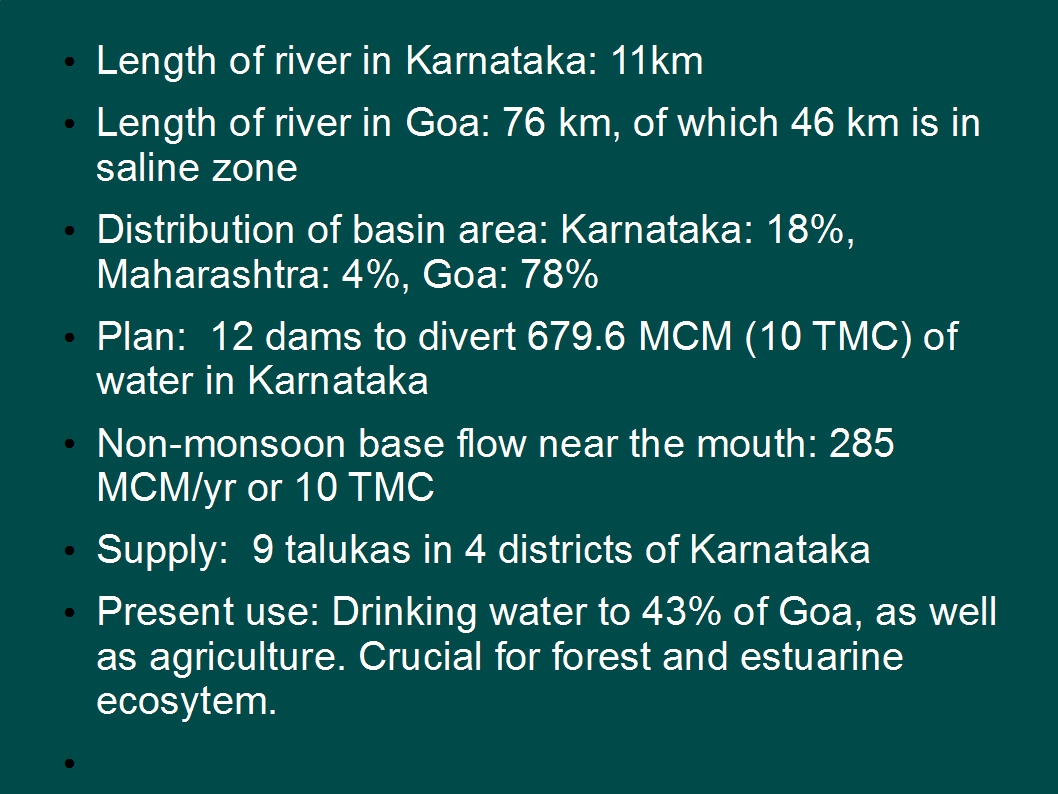

What many of us outside the area may not know is that the Mandovi has a double identity. For the first 35 kilometers of her 87 km length, she flows through Karnataka and is known as the Mhadei. Here, the river is not a lifeline but a promise--one that has led to a bitter fight between the two neighbouring states.

The dispute

In 1973, Karnataka's attention was first drawn to hydropower generation from the Mhadei. Since then, the state has planned a series of dams on the Mhadei's tributaries. In 2002, Karnataka--without consulting Goa--successfully approached the Ministry of Water Resources and asked to divert 7.56 TMC of water from the Mhadei basin to the Malaprabha basin. According to S T Nadkarni, Chief Engineer, Water Resources Department of Goa, “Karnataka is planning 12 dams on all tributaries to divert all water to the Malaprabha and Supa reservoirs.” This series of dams is hotly contested by Goa especially since there is an increase of demands since the idea was first proposed.

A N S Nadkarni, Advocate General of Goa, confirmed this statement. "Karnataka now wants to divert 24 TMC of water from the basin. First they said it is only for drinking water, but Goa proved that politicians have promised irrigation water to the people of Karnataka." Though the issue is still with the Tribunal, Karnataka is proceeding with the construction of the Kalasa-Banduri canals.

What Karnataka wants

While Karnataka has not yet been able to use the waters of the Mhadei within its catchment, water is in high demand in the state's central districts. Vijay Kulkarni, President of the Kalasa-Banduri campaign committee, explained, "The water diverted from the Mhadei basin will be used in 9 talukas of 4 districts in the state. Presently there is a dire shortage of water in that area. The only source of irrigation is through borewells which few farmers have; several villages are tanker fed." Supporters of the diversion--notably Prithviraj Chauhan, ex-CM of Maharashtra--maintain that "the water is being wasted as the river empties into the sea." There have been several demonstrations in Karnataka seeking this diversion.

Goa disagrees

The coastal state hotly disputes the idea that water flowing into the sea is a waste--they are aware of saline ingression. Already, 52 km of the Mandovi's 76 km length in Goa lies within the saline zone.  Pratap Singh Rane , leader of the opposition in Goa, clarified, "In the summer, salt water comes up to Usgaon. Just above Usgaon are our drinking water jackwells and agriculture belt. If there is no fresh water in the river, salt water will go further upstream". Besides their drinking water and livelihood, the Goans are concerned about the impact on the Mandovi's ecosystem. The region where the Mandovi enters Goa is one of the most pristine forests in the Western Ghats, which is itself a biodiversity hotspot.

Pratap Singh Rane , leader of the opposition in Goa, clarified, "In the summer, salt water comes up to Usgaon. Just above Usgaon are our drinking water jackwells and agriculture belt. If there is no fresh water in the river, salt water will go further upstream". Besides their drinking water and livelihood, the Goans are concerned about the impact on the Mandovi's ecosystem. The region where the Mandovi enters Goa is one of the most pristine forests in the Western Ghats, which is itself a biodiversity hotspot.

The controversy

Each of the points made by Goa and Karnataka is refuted by the other. Some of these points are factual while others are just the states' points of view. If Karnataka claims that Goa does not utilise (i.e. extract) all the water, Goa points out that instream flows are crucial to the state's agriculture and drinking water. While Karnataka asserts it is only claiming its rightful share under equitable principle, Goa accuses Karnataka of being a bully.

The Minister of Water Resources for Goa, Dayanand Manjrekar, said, "Karnataka is forcing the issue upon us." Nadkarni claimed that "Karnataka is a singular state which has water disputes with all its neighbours. Like we have an Education Department, they have a Disputes Department." Karnataka’s water resources minister M B Patil believes that Goa is totally devoid of any humanitarian consideration.

It is unlikely that the issue with be laid to rest when the tribunal gives its decision. Rajendra Kerkar, Secretary of the Mhadei Bachao Andolan, said, "The government of Goa has undertaken to stand by the Tribunal's decision no matter whose favour it is in. But this is not a dilemma that can ever be solved. The struggle has no option but to go on." Vijay Kulkarni was more direct. "If the result is not in our favour, we have planned a big demonstration."

Beyond the Mhadei or Mandovi

Why should we worry if two states are engaged in a never-ending dispute over a 87 km long river? Because they are not alone.

Water harvesting should be in every regional development plan. - Adv. Nadkarni

Every state in the Peninsula is engaged in a water dispute with at least one of its neighbours. The main rivers of the Indian Peninsula--Cauvery, Krishna, Godavari, Narmada and Krishna--are all the subject of Tribunals. Besides this, there are several other disputes in the country over the sharing of waters and upstream-downstream rights. In Northern India, the issue acquires an international dimension; water is a source of tension between India and nearly all of her neighbours.

The Ministry of Water Resources recently acknowledged that cooperation of all the states is essentially required for the success of the Interlinking of Rivers Programme. Within the present federal system, it is unlikely that this cooperation will be achieved. This is true of all the proposed links, but especially so where sharing waters of the rivers concerned are already under dispute. The other alternative, which is to bring rivers under the Centre, has the potential to create new problems while failing to resolve existing ones.

Is there a solution?

The answer comes from the people involved in the dispute. Kerkar pointed out, "Trying to resurrect a dying river or transferring water from outside is futile. Neither is it ecologically sound nor is it politically possible when there are fights within villages." Instead, he suggests that governments and communities should protect the catchment areas of their local rivers. This needs to be combined with water-wise agriculture, by selecting a cropping pattern that is appropriate for the region's water availability.

This sentiment is echoed by Nadkarni who advised, "Water harvesting should be in every regional development plan. It is the fundamental duty of every citizen to harvest water."

Or as Prof. Ramaswamy Iyer said, "Forget Prometheus and remember Bhagiratha", as he argued for a shift from the techno-centric manipulation of rivers to learning to co-exist with them.