What happens when two or more states are dependent on same water resource for agricultural purposes ? Do the states compete for the resource or are their needs sufficiently different from each other? What are the consequences of the competition for this precious resource?

This article sheds light on the dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, for sharing Cauvery river water. The ongoing tussle between the two states has seen a lot of unrest amongst farmers in form of dharnas, protests, rail roko and non-cooperation by citizens, and disagreement with the agreements made by their respective governments and unending negotiations by governments involved, to come to a mutually agreeable decision.

Even the common man knows that Cauvery is a deficit river, where the total quantity of water available in a year is estimated to be 740 TMC (thousand million cubic feet) and the demand 1260 TMC. Four states viz., Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Pondicherry, are vying for a share of this scarce resource, even though the major fight is between the first two states.

To find an amicable settlement to the dispute, the Supreme Court constituted the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal in 1990 which gave its interim order in 1991. As the order was contested by the stakeholder states, the arguments continued until the final order was passed in February, 2007. This order when gazetted will supersede the earlier agreements of 1892 and 1924 between Mysore and Madras states.

The demand by the states and the allocation by the Tribunal are as follows:

S.No | State | Demand (TMC) | Allocation (TMC) |

1. | Kerala | 92 | 30 |

2. | Karnataka | 465 | 270 |

3. | Tamil Nadu | 566 | 419 |

4. | Puducherry | 9 | 7 |

5. | Total | 1260 | 726 |

Source of data: Final order of the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal

The Tribunal reserved 10 TMC of water for environmental protection and another 4 TMC for the inevitable escape into the sea. The total amount of water allocated for Tamil Nadu is 419 TMC, and 192 TMC has to be released from Karnataka in a month-wise schedule. This becomes an issue in below normal rainfall years.

With this deficit allocation, there is not sufficient water to sustain the existing cropping pattern in the command areas with presently followed water management practices. The order also puts a cap on irrigation command areas as they existed in 1991, several lift irrigation schemes that came into existence later will not be entitled for water from river Cauvery. The order also affects the drinking water supply to Bangalore as only 1/3 area of the city falls in the basin.

Cauvery command has substantial area under paddy and sugarcane, which require higher quantities of water of about 1200 and 1800 mm respectively, compared to dryland crops like ragi (500 mm). Large areas in Tamil Nadu have a practice of growing 2-3 crops of paddy (Kuruvai in June, Thaladi in September and Samba in August). While allocating water, the Tribunal considered the existing usage of land and allowed double /triple cropping wherever the practice existed prior to 1924, but did not make any allocation for the areas developed after 1991. Both of these have become contentious issues.

Before passing the final order, the Tribunal heard the expert witnesses from all the four states. Dr. I.C. Mahapatra, one of the experts, has categorically stated that ‘rice in both the states should be restricted only to one crop and confined only to the rainy season’. Even the National Commission on Agriculture has recommended that ‘rice should be grown preferably where there is good rainfall’.

To solve the Cauvery water crisis, farmers of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka should go in for less water-intensive crops such as pulses, oilseeds and millets (Illustration courtesy: Sourabh Phadke)

But what is actually happening in both the states is exactly opposite. Kuruvai crop in Tamil Nadu and summer paddy in Karnataka are grown in the non-rainy season. Tamil Nadu’s contention that Karnataka should not grow any summer crop, so that sufficient water for raising Kuruvai crop in Thanjavur is reserved in Karnataka reservoirs is not practical.

Paddy is preferred mainly because of the tradition, even when other crops like pulses and ragi are more nutritious and fetch an equal or better price in the market. It is unfortunate that our efforts are concentrated in preserving unsustainable traditions, rather than putting the available water resources to better use.

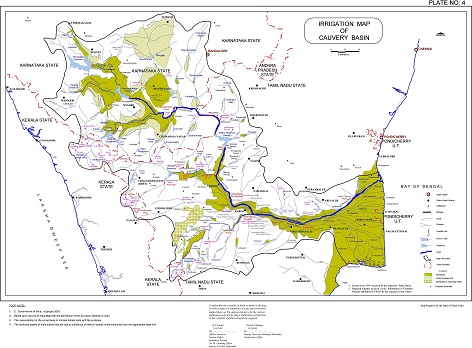

Irrigation map of Cauvery basin as on 14 January 2013 - Source: Ministry of Water Resources

(Click on the map to view the high-resolution version)

The first step to change over to a sustainable practice will be to effectively convey to the farmers that there is simply not enough water for more than one crop of paddy. Further, it is essential to drive home the point, that paddy can be cultivated just by keeping the soil moist and that there is no need to impound or allow water to flow from field to field. Paddy should be substituted by remunerative pulses, oilseeds or millets based on the availability of water.

One will have to take into consideration water availability from all sources in the field for preparing an effective cropping plan. This includes ground water. The present order of the Tribunal has consciously avoided the groundwater contribution in all the four states and does not give a scope for preparing a conjunctive use plan.

The Tribunal has also not given clear guidelines on sharing water during distress years. As available water depends primarily on rainfall, the monthly rainfall in the catchment area can give a good estimate of river flow. The selection of rain gauges for this purpose has to be decided mutually by the user states.

Farmers in the command area are more concerned about availability of water rather than its exact quantity. Nobody is interested in perpetual conflicts and periodical disturbances. Unless the politicians and policy makers realize the importance of peaceful neighbourly relations, our arguments in the court, merely based on past use, is going to be a futile legal battle.

Dr BR Hegde was formerly Director, Research with the Gandhi Krishi Vignyan Kendra (University of Agricultural Sciences), Bangalore.