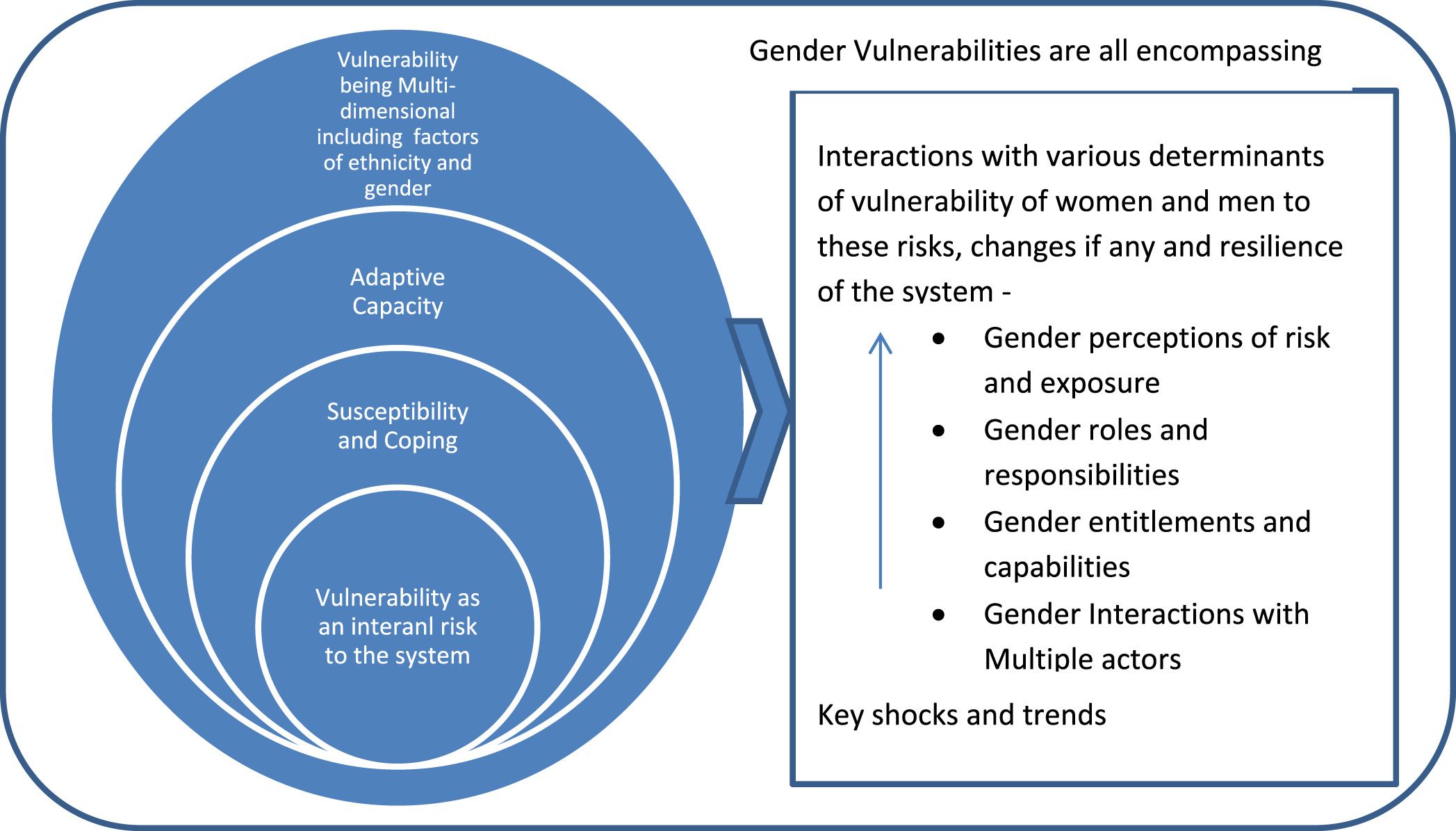

Climate change impacts are disproportionate and influence lives and livelihoods variedly. One crucial determinant of these disproportionate impacts is gender. Existing social norms determine roles and responsibilities, entitlements and capabilities, thereby influencing the individual perceptions of shocks and susceptibility which vary across gender groups.

The paper ‘Livelihoods, gender and climate change in the Eastern Himalayas’ seeks to draw insights from the various field studies conducted in these locations to understand the gender vulnerabilities that manifest through a combination of complex and interlinked factors. It seeks to understand the existing social practices typically associated with these gender groups in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region and how changes in the climate potentially influence vulnerability.

The study makes use of qualitative research methods to understand the gender roles, responsibilities. The role of place-based vulnerability in influencing lives and livelihoods is stressed.

The study sites in Sikkim are spread from about 600 to 1200?m in the mid elevation regions to 2000 to 3200?m in certain regions and 4000 to 4500?m in the Trans-Himalayan zones of Gurudongmar and Muguthang. The Teesta basin draws its waters from glaciers and snow from North Sikkim and many other tributaries flowing from other parts of the state including West Sikkim, which are glacier dependent. People living in these mountains face huge complexities arising from a number of factors including terrain characteristics, micro-climates, environmental degradation, access to basic services etc.

The study framework

The paper emphasises on the role of ethnicity, poverty and political identity in shaping gender vulnerabilities in the Eastern Himalayan context. The study considers the various capitals – natural, social, physical, financial, human and political from the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) (DFID, 1999) in the analytical process of the content collated from the study sites.

Gender entitlements and capabilities in the study area

Mountain regions are highly sensitive to extreme events which combined with arduous terrain presents further challenges for both men and women. Moreover, given the reliance on climate-sensitive livelihoods, like farming and livestock rearing, greater exposure to vulnerabilities is experienced in the Teesta basin.

Women stand to be highly vulnerable in most cases to the changes in the climate and its extremes. While incomes are affected and influence vulnerabilities, availability and access to water sources in the mid elevations constitutes as a primary reason for enhancing vulnerabilities. Those near the water sources and traditionally settled have better access to the resource compared to settlements that have moved into those areas from other locations.

Also, marginal landholders (<0.5?ha) and those with no livestock are the most vulnerable given their income sources are not diversified. The marginalised groups including women have been found to be particularly vulnerable to climate change as a result of their limited access to assets, influence, control over resources, and networking to access services and institutional support.

The study reiterates the place based sensitivities to climatic and environmental aberrations that exist and which are reinforced due to underlying socio-economic conditions. These sensitivities vary by caste, ethnicity and location.

In high elevation regions, both men and women are exposed to harsh weather conditions. While women migrate seasonally to low elevation regions and manage other work including homestays, some men folk remain behind to manage the cattle, especially yaks. Tourism in the high elevation regions is affected during the winters as very cold temperatures prevail. This includes impacts on homestays and hiring of yaks, porters etc. Communities however are self-sustained and are able to support themselves with the food they grow and with support from livestock.

Women are, to a large extent, not involved in financial dealings and decision making surrounding it. In some places women do handle the day to day cash flows but larger financial decisions are in the control of men. The poor social capital of women interplays with lesser exposure to and understanding of early warning systems, lack of information accessibility, as a result of age old norms and practices being followed eventually reduces the ability of women to take protection measures during disasters thereby increasing their vulnerability to extreme weather events.

It is observed that the knowledge on the biodiversity varies by both men and women and therefore needs to be preserved. Engaging women in income-generating activities and providing ownership would help empower many women.

These gender differentiated vulnerabilities influence lives and livelihoods in an intertwined and mostly unseen ways. Most of these are a resultant of existing social constructs and dependence on environmentally sensitive livelihoods. Thus, understanding how inequities in decision making manifest and therefore propagate vulnerabilities, is a crucial step towards addressing gender in climate policies. However it also important for policies to explicitly acknowledge the need to account for gender dimensions along with other social differentiation factors to enable a conducive action oriented environment to address entrenched gendered vulnerabilities.

Key findings of the study can be summed as:

- Livelihood diversification and education can potentially influence vulnerability of communities.

- Gender specific differences in vulnerabilities arise due to variations in roles and responsibilities associated to these gender groups.

- Gendered vulnerabilities are exacerbated by lack of access to natural, financial and social capital.

- Targeted policies that seek to address these underlying issues of access to or availability of capitals must be built in climate hotspots such as the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region.

The full paper can be accessed here