Press conference on the release of the research being addressed by Shankar Gopalakrishnan, Madhu Sarin, Arvind Khare and Viren Lobo (left to right)

Image courtesy: Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development, New Delhi

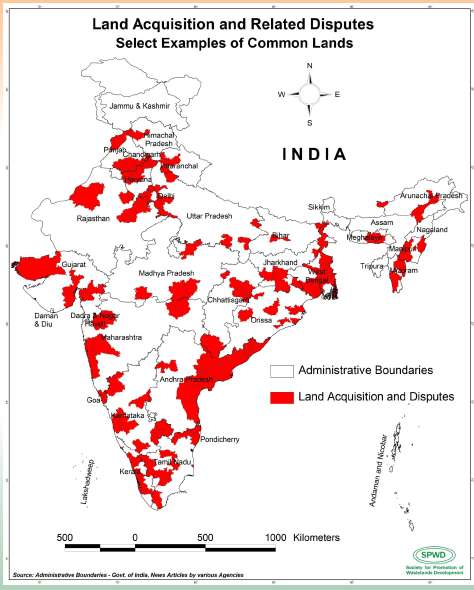

The ongoing land takeover in India is captured in new findings released recently and illustrated on a map recording recent protests in 130 of India’ 602 districts, in virtually all states of India, most of which took place in 2011 and 2012. The government agencies and investors are responsible for a growing spate of violent clashes in the nation’s forest and tribal areas. The study argues that the reports of civil unrest, gathered from a review of newspaper articles and court cases, are the outcome of a massive transfer of resources from the rural poor to investors, aided by the government.

Land acquisition disputes in India

Image courtesy: Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development, New Delhi

The report was released at a conference that dealt with how the tribal and rural communities, with tenuous rights on forests and other common lands, face increasing deprivation of their livelihood resources despite the inherent constitutional and legal guarantees under these. The conference presentations from the tribal states and the overarching study highlighted the dimensions of the problem and intense resource conflicts afflicting the uncultivated half of India.

Madhu Sarin in her presentation noted that a third of the Indian population is impacted by land and forest takeovers and every state in India—as well as every forest—is embroiled in land rights disputes. These disputes play out in court and on the street, in the form of hunger strikes, mass demonstrations and violent uprisings. The Government of India estimates that 10,000 armed fighters and 40,000 supporters are involved in violent struggles in rural India that often include disputes over land rights.

The nation can expect rising civil unrest in response to major projects planned for the next 15 years, requiring over 11 million hectares of land and affecting the livelihoods and welfare of millions of people. Jagdish Purohit, SPWD based on current and projected land required for development projects in India stated that “Currently, 65,112.66 sq km of land, most of which is common land and forests, is devoted to projects in four sectors: agri-business, infrastructure, extraction activities and nonconventional energy sectors. In 15-20 years, 114,475.59 sq km of additional land, mostly common land, will be taken over by the state and other actors to accommodate major projects that are already in the planning stages. Agri-business (56,263.00 sq km) will need most of the additional land, followed by infrastructure activities (23,657.09 sq km).”

According to Shankar Gopalakrishnan, India has legislation on the books already that could address the root causes of the conflicts reported in the studies. However, acquisition of the forest and other common lands for various purposes has not yet received the attention of the policy makers despite the raging debate on the new Land Acquisition, Resettlement & Rehabilitation (LARR) Bill meant to replace the 1894 Land Acquisition Act.

Two key examples are the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act of 2006, which is designed to protect forest dwelling and tribal people from illegal takeovers, but is being routinely violated; and the 1996 Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (the PESA Act), which gives village councils, known as gram sabhas, powers to manage and protect their lands State laws that provide for community and collective rights and management powers are also ignored and violated across the country, according to Viren Lobo, SPWD.

Image courtesy: Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development, New Delhi

Land takeovers by India abroad

Arvind Khare, RRI speaking at the Conference noted that India has joined the ranks of China, South Korea and Saudi Arabia—"land-deficit" countries snatching up stretches of prime agricultural land in developing countries to grow crops for domestic or global markets. Land deals are rarely transparent, so information about them is limited. Some organizations, including the International Land Coalition (ILC), have attempted to track these deals. They find that the Indian government and Indian-owned companies have acquired land in Africa, South America and Southeast Asia for agricultural purposes.

According to the International Land Coalition (ILC) Land Matrix, the scale of Indian investments has reached 6.3 million hectares (ha) or 63,000 square kilometers (sqkm). The current convergence of interests between communities, investors, and forward looking governments provides an unprecedented opportunity to reverse historical injustice and change the future of community lands, Khare noted. Benefits come from reductions in risk, conflict prevention and decreased poverty.

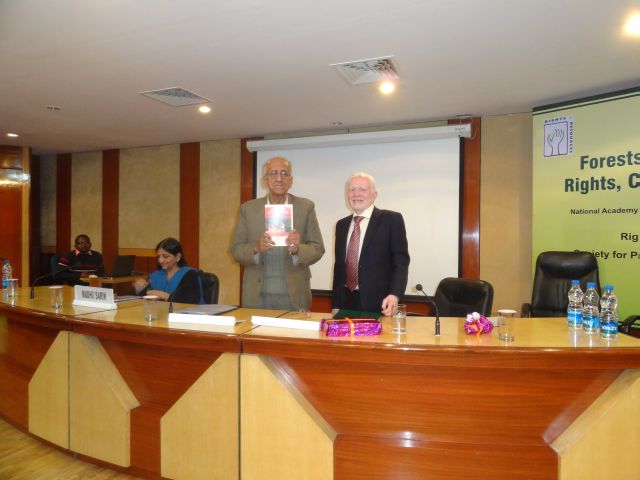

India release of the book titled "Deeper roots of historical injustice: Trends and challenges in the forests of India"

Image courtesy: Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development, New Delhi

International experiences: Case of Brazil and China

Brazilian forestry expert Luiz Carlos Joels, one of the speakers at the conference, speaking on the topic of “Traditional populations and forests: An overview of Brazilian policies” said that the colonization in Brazil was based on distribution of land to Portuguese, land grabbing and forest conversion. The cultural identity and originary rights of the indigenous people were not recognized at that time. Once the 1988 constitution of Brazil recognized that lands traditionally occupied by indigenous peoples are essential to the preservation of environmental resources and necessary to their well-being, culture and traditions, the situation changed completely. The rights of indigenous peoples have now been recognized and demarcated in over 100 million hectares of territories. Joels said.

Joels also presented a case study on Gurupa where he dealt with the community-defined environmental rules and forest management activities before formal tenure rights were ensured. There is a strong link between tenure and community based forest management in Amazonia. Tenure solutions must consider community characteristics, their forms of using the resources and their wishes. Community-based guidelines for resource use are important and set the basis for the type of tenure most appropriate for each community. The struggle for tenure and resource use has a positive impact on citizenship and on the creation of social capital.

Professor Xu Jintao, an economist at Peking University presented the overview and preliminary analysis of “Collective forest tenure reform under village democracy”. He said that “China’s economic progress is fundamentally based on agrarian reforms of late 1970s and forest tenure reforms in early 21st century—both of them recognizing rights of people over their resources.” It was a step towards completion of rural land reform. The tenure choice in China was dominated by rural governance structure. Xu noted that reform increased forestation area by 8 per cent in the country.

In the Conference, a set of forward looking policy options and changes in the implementation structures were presented that could help in transforming the livelihoods of the poor, securing investments on fairer terms, and resolution of conflicts. Participants identified the options for reform that would help in ushering in a fairer and inclusive path of development in some of the poorest areas of the country.

Compendium of case studies

A compendium of case studies on takeover of common lands in India was prepared by SPWD in an attempt to fill the gap in the available literature on the subject of land takeover in the country. It represents one of the first attempts to look at this issue at the national level, drawing together local situations and experiences into an overall legal and policy framework. This was followed by a report by Shankar Gopalakrishnan that sought both to present a synthesis of the findings of these studies, reflecting the overall situation at the national level, as well as to discuss possible policy actions that can be undertaken.

Bauxite and Zinc mining in Orissa

Vedanta is a large metals and mining firm with an emphasis on bauxite and zinc. The case study documents the company’s attempts to access and refine bauxite in Orissa and the large-scale local opposition that this has led to. This unrest, along with substantial international reaction, eventually convinced the national government to investigate the issue of tenure disputes. Following a damning report by the MoEF, ministers denied Vedanta access to forest reserves. The company also suffered from high-profile disinvestments, as a result of NGO campaigns and reputational damage. Credit ratings agencies reacted to tenure-related losses by putting Vedanta on negative outlook.

The problem for Vedanta was that the bauxite reserves it wanted in the Niyamgiri hills lay under land of high cultural and spiritual importance to indigenous peoples. Mining operations would have deprived these communities of the land on which they have lived and relied for generations. Vedanta could have made an effort to mitigate the social and environmental impacts of its activities, but it seems to have viewed these activities as too costly.

Phosphate mining in Rajasthan

Since 1972, phosphate has been mined in the district of Udaipur by the state-owned Rajasthan State Mines and Minerals Ltd. (RSSML). In addition to the mines, RSSML set up a processing plant and fertilizer factory in nearby villages to process the phosphate into fertilizer. Open cast in nature, phosphate mining requires large areas of land for the dumping of material.

In 1968, the government acquired land for mining and transferred it to RSSML; since then, RSSML has taken over both common and private land in these panchayats (villages). Common lands have been handed over to the company on the signature of a local government official, the patwari. Forest land has also been transferred for mining. The gram sabhas (village assemblies) were not consulted regarding the acquisition of land, the transfer of common land, the renewal of mining leases, or the diversion of forest land, despite legal requirements under the PESA. The claims of forest dwellers in these villages are still pending under the Forest Rights Act. The case study documents these issues.

Illegal iron ore mining in Bellary, Karnataka

In the last decade, Sandur taluka in Bellary, Karnataka, has seen a massive expansion in iron ore mining. Driven by the growing Chinese market, the liberalization of mining regulations, and a decision by the Karnataka government to denotify large areas of notified forest land in the area, large companies, small contractors and even local farmers have begun ore extraction and trade.

A large part of this activity has been illegal. Legal violations include mining without the required lease from the government; mining without obtaining environmental clearance or forest clearance; mining even after leases have expired; and mining beyond the lease area; failing to comply with transport regulations. Much of the mining has occurred on forest and common lands as per the case study. The enormous profits from legal and illegal mining have driven large-scale corruption in the area, with mining barons becoming immensely rich and powerful.

Sand mining in Rajasthan

The Aavara river flows through the Udaipur, Rajasthan. For more than 30 years, the stretches of the river passing through some villages have been mined for sand. Currently, an estimated 19,200 tons of sand are removed daily from an area of around 1,000 hectares. These activities have led to the lowering of the river bed and the widening of the banks; measurements at some sites show the river bed dropping annually by around 3.5 feet (approximately one meter).The surrounding villages have suffered as a result of this sand mining. The fall in the river’s water level have led to the drying up of some wells and the collapse of others due to the removal of sand from their walls. This lack of water has led to falling crop yields in the area.

Licenses and regulation of the sand mining is done by the State government with no local involvement. Recently, however, the gram panchayat (village council) has taken steps to ameliorate the impact of the mining by building check dams and water ponds. The villagers have also started planning to switch to alternative and more sustainable crops, according to the case.

Highway building in Rajasthan

Highways and other ‘linear’ projects (railway lines, transmission lines, pipelines, etc.) have received relatively less attention in discussions on land takeovers and displacement. One example is the Rajasthan State Roads Development Corporation's attempted redevelopment of a stretch of State Highway 53, between the towns of Keer Ki Chowki and Salumber. Construction is still underway.

In the area studied, common pasture land, revenue ‘wasteland,’ and private pasture and agricultural lands have all been acquired/ taken over for the road project and associated toll plazas. Through the exploitation of an ambiguity about land falling in the “right of way,” some private lands have been taken without paying any compensation. Regarding common lands, neither payment nor consultation has taken place. Moreover, stone and quartz quarrying on common lands alongside the proposed new road has occurred without consultation with local communities, payment or compensation.

Biofuel plantations in Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh

Two states in particular, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, have been at the forefront in promoting biofuel porduction. In 2006 and 2007, respectively, these two governments notified new rules under their respective Land Revenue Codes, mandating the identification and allocation of "wasteland" for biofuel plantations.

In Rajasthan, plantations were to be carried out by the Forest Department, gram Panchayats or SHGs; however, the State government also invited private companies to engage in plantations, provided that they also set up a biodiesel plant. Since 2010, the Chhattisgarh government invited the formation of joint venture companies to engage in biofuel plantations. As a result, 157,332 hectares of land in the state has been classified as ‘wasteland’ fit for biofuel allocation; in Rajasthan, authorities have identified 41,127 hectares for the same purpose.

Most of this land, however, is common land used for grazing, forest produce collection, etc.; some of it is under individual cultivation. The mis-identification of these lands as ‘wastelands’ and their allocation to biofuel plantations threatens to deprive large numbers of adivasis (indigenous people), forest dwellers and other marginalized communities of their livelihoods and basic resources.

The process of identification and allotment has been carried out entirely by district authorities, without consultation with local communities. In the process, such laws as the FRA and the PESA Act have been grossly violated. The case describes the resistance by those affected and the lack of state response to the concerns of the affected communities.

Polavaram dam in Andhra Pradesh

The Polavaram project in the State of Andhra Pradesh is one of India's largest dam projects. Under consideration for over 70 years, the project involves a large dam on the river Godavari and a linked canal network, with the stated aim of irrigating agricultural lands in the area. If built, the dam will submerge an estimated 276 villages across three districts in Andhra Pradesh, along with 27 other villages in Chhattisgarh and Odisha.

The case study deals with the problem of submergence and loss of livelihoods and access to land. More than 45 percent of the land to be submerged is either village common lands (including pasture) or forest. Though the Forest Rights Act requires that any diversion of forest land be preceded by completion of the rights recognition process, the Central government granted final forest clearance to the dam in July 2010 on the basis of a one line assurance from the State government. The government also subverted the provisions of the PESA Act by consulting higher bodies (the mandal panchayats) instead of village assemblies before acquiring private land.

As mandatory rules on public hearings were not complied with, the National Environment Appellate Authority struck down the dam's environmental clearance in 2011; the State government won a stay order from the AP High Court on this judgment, allowing them to go ahead. However, MoEF at the Centre has requested the Andhra Pradesh government not to proceed with construction until questions about the environment clearance are settled. Petitions against the dam are pending before the High Court and the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, allegations of corruption in the tender process have surfaced and led to a cancellation of tenders by the High Court in February 2012.

Wind turbines in Andhra Pradesh

Though historically an area of dense forest, Anantapur district of Andhra Pradesh is today an arid zone with only 2 percent forest cover and persistent drought. Under such conditions, a local group, Timbaktu Collective undertook eco-restoration of forest and common lands starting in 1990. They focused their initial efforts on a 32-acre patch of land; later, their work covered approximately 100 villages in the surrounding area.

In seven villages of the Chennekothapalli and Roddam mandals (sub-districts), the collective has worked since 1992 to restore an area of around 3,400 hectares known as Kalpavalli. The collective transformed the once barren, stony and dusty Kalpavalli landscape into a mixture of deciduous forest and grasslands with a network of community wells. Wildlife has returned to the area. The land is now used extensively by the surrounding villages as pasture land, for the collection of minor forest produce and fuelwood, and for water storage and distribution.

On revenue records, however, the land continued to be recorded as ‘unassessed waste’. On this basis, the State government allocated 28 hectares of land in 2004 to the wind energy company Enercon to construct 48 wind turbines. The case study deals with the problems that have emerged like damage to soil, water scarcity, reduced catchment areas and the dumping of rubble. The state made no attempt to consult communities regarding use of the common lands, and Enercon has disowned an agreement signed by its lawyer with the Timbaktu Collective. The case study documents how the Collective is continuing its fight to stop the expansion of the wind energy project, including by exploring legal options.

The Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI) is a global coalition of international, regional, and community organizations advancing forest tenure, policy, and market reforms.

The Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) has been working closely on issues related to natural resources, ecology and livelihoods and its implications for governance.