A recent book ‘Transforming Food Systems for a Rising India’ by the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI) at Cornell University provides a detailed assessment of the major paradoxes of the Indian growth story. It is marked by the simultaneous existence of regional inequality, rural and urban food insecurity, intractable malnutrition problems and the growing incidence of overweight and obesity.

Despite positive economic growth trends, the country continues to struggle with malnutrition manifested in terms of high rates of child stunting and wasting that are substantially higher than other countries with similar economic growth experience and at similar stages of structural transformation.

Crowding out of nutritious grains

India’s food and agriculture policy have historically focused on enhancing supplies and access to staple grains, especially rice and wheat, and thereby have had considerable success in reducing the incidence of hunger in the country. While it is true that millions still suffer from hunger, imagine what the situation would have been if the country did not invest in productivity improvement for the major staples through the Green Revolution. However, the singular focus on enhancing rice and wheat supplies may have inadvertently resulted in the crowding out of the more nutritious grains, such as millets and other coarse cereals, and pulses.

Staple-grain-focused policies may have also created disincentives for farmers to diversify their production systems in response to rising market demand for non-staple food, such as fruit, vegetables and livestock products. The imbalance in protein, vitamin and micronutrient supply in the food system is a major cause of the high incidence of malnutrition in India.

Poor sanitation, lack of access to clean drinking water and low levels of women’s empowerment are other proximate reasons for the persistence of malnutrition in India.

Even while India struggles to address the undernutrition problem, emerging trends in overweight and obesity portend to a future public health crisis in non-communicable diseases.

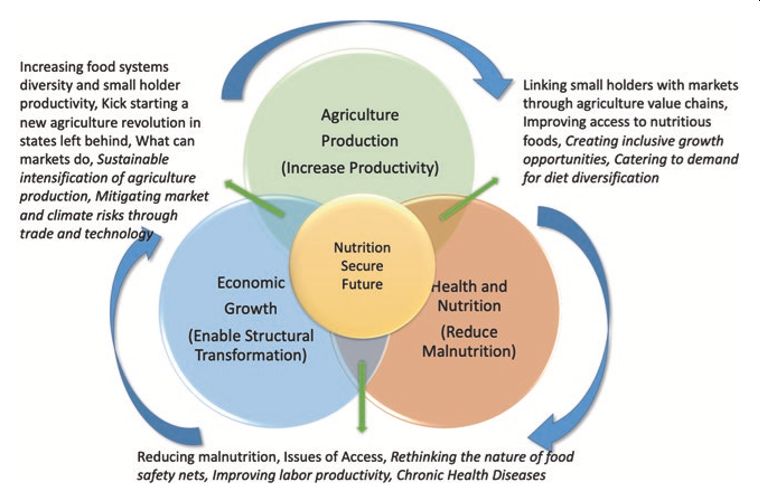

The book examines the nexus of economic development, agricultural production and nutrition through the lens of a “Food Systems Approach (FSA)”.

“Central to our vision for a robust food system is a future where nutrition-secure individuals have the capability and the opportunity to improve their health through greater access to a balanced and healthy diet. In order to implement a holistic approach towards economic welfare and nutrition security, we link the goals for agricultural development, health and nutrition and economic development with each other”, says Prabhu Pingali, Professor of Applied Economics and Founding Director of the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI) at Cornell University.

It brings together the latest data and scientific evidence from the country to map out the current state of food systems and nutrition outcomes. India is placed within the context of other developing country experiences and its status as an outlier in terms of the persistence of high level of stunting while following the global trends in overweight and obesity discussed.

The book deals with the policy and institutional interventions needed for promoting a nutrition-sensitive food system and the multi-sectoral strategies needed for simultaneously addressing the chronic undernutrition and emerging over-nutrition problems in India.

The key takeaways from the book are:

- The differential growth experience of Indian states can be explained by their initial investments in agricultural productivity growth and their subsequent focus on robust non-agricultural employment growth.

Meeting the growing urban demand for food and other agricultural products and non-farm employment provides new growth opportunities for rural economies; the challenge is to ensure that it is inclusive of the poor.

- Diet transition and the rising demand for food diversity is not matched with a commensurate rise in the supply of non-staple foods leading to poor access to more nutritious food.

While progress is being made on undernutrition, the emerging nutrition transition towards over-nutrition and the rising incidence of non-communicable diseases requires a move away from policies that promote calorie sufficiency to ones that promote food system diversity.

- The objectives and design of India’s safety net programs, whether food or cash based, need to evolve with economic growth and the changing nutritional needs of the marginalized populations.

- Promoting small farm commercialization and diversification serves the dual objectives of enhancing farm incomes while improving the supply and access to food system diversity.

- Effective aggregation models, such as producer groups, can help reduce the high transaction costs of small farms accessing urban food value chains, especially for fresh food.

- Technology will continue to play a vital role in enhancing smallholder productivity and competitiveness, but it’s time to look beyond staple grains, and take a holistic view of the technological options for promoting a diverse food system.

Climate change can have significant adverse impacts on agricultural productivity, rural incomes and welfare; in addition, it can pose serious risks to the nutritive value of the food system since it can have a disproportionately higher effect on non-staple foods.

- Food and agricultural policy need to transition from a focus on quantity to emphasize quality, diversity and safety. It should also leverage multi-sectoral synergies with economic growth, improved access to clean drinking water and sanitation and behavior change for promoting improved diets.

The full book can be accessed here