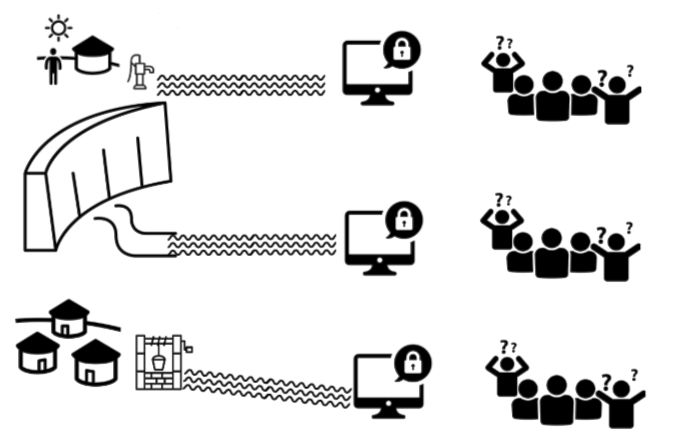

A few of us did an exercise where we closed our eyes and thought of the first four words that came to our minds when we thought of water data in India. Here is what we came up with:

- Where (is it)? - Pointing to a large vacuum in data availability.

- Management Information Systems (MIS) - created during a program’s life as a method for the funding and oversight agencies to know what is happening on the ground.

- Unusable - Most of the data in the public domain is not available real-time, making it irrelevant to the decision making today.

- God knows! - who collects this data, what training did they receive to collect it, how is it updated into the system - all pointing to whether it paints the right picture.

All these words, we realised, point to one fundamental problem - a lack of trust. We also realised all is not lost. Programs - both governmental and non-governmental are making rapid strides in terms of tools used to collect data and dashboarding this data. Simple, open tools are being developed to urge better data collection and visibility to actors within a program.

Most of these tools, in turn, feed an MIS, which is set up to track and monitor the programs. In fact, programs spend a substantial amount of human and capital resources on their MIS. However, when the program ends, this MIS expires as well. When the next program comes in, it starts with its baseline - and once again leaves no data behind.

Can we break this cycle?

Yes, we can. Let us understand how by using two current programs of the Government of India: the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) and Atal Bhujal Yojana (ABhY). Together, these programs will reach more than 6 lakh villages, collecting data from each of them to generate plans. The Water Security Plan (WSP) mandated by ABhY has more than 225 attributes to be collected which will involve intensive community engagement. Similarly, the Village Action Plan (VAP) under JJM has more than 130 attributes, some of which overlap with data collected for the WSP, especially the component under source sustainability.

If implemented well, this data will be inherently owned and trusted by the community as both program designs have rightly put them at the centre of these schemes. In villages where both the programs will be implemented, making data from one available to the other is a no-brainer to ensure convergence and optimum outcomes.

This seamless flow of data from one program to another can be enabled if a few principles are kept in mind:

Community as data owners and users

Keeping the subsidiarity principle in mind, data should be made available to the community in a way that builds their agency and empowers them to make the right decisions. Involving the community in a data framework with the right incentives will have the second-order benefit of the community being active collectors of data, allowing for annual VAPs/WSPs to be created leading to a virtuous cycle that lasts beyond the programs. This is also in line with the first Disbursement Linked Indicator (DLI) in ABhY that calls for making data publicly available.

Trust in data

Data abundance will lead to usage and improved decision making only if there is trust in data. This is possible through Digitally Verifiable Registries (of people, entities, tools and assets that participate in the network) with open application programming interfaces (APIs) that can amplify trust and accountability across the network.

This will ensure that personnel collecting data will be tagged to these data sets (in ways that keep their privacy in mind) and the capacity building done as a part of JJM and ABhY will, in turn, be tagged to them thus reinforcing trust in data.

Data as an exhaust

Simply put, this means that data is available in run-time as a part of workflows within the program, without creating new workflows solely for the purpose of data collection and uploading. ABhY lays a strong foundation for this by ensuring the right infrastructure is made available at the GP-level.

Use of open standards

It is necessary to create open standards and certification mechanisms to ensure neutrality and interoperability among devices, sensors, and systems.

For instance, every vendor that sells a water quality test to ABhY or JJM understands the minimum specifications for the device to qualify as viable and usable by the program. So, multiple vendors can build devices for the program, given the huge demand, which in turn can drive down costs.

Incentive aligned collaborative design

There is a need to create an environment for data sharing to empower all the actors and amplify the collective ability of the ecosystem to leverage what exists. It can also enable actors to act, solve the problems, and contribute back as required for creating a data-rich economy. We need to invest and think deeply on designing these incentives and collaborate more to make them a reality.

Given the potential that these programs have to enrich data availability in the water sector, there is a huge potential to reimagine the MIS of these programs to provide program-agnostic data and artefacts to the ecosystem at a granular level in a trusted manner to empower ecosystem actors.

By doing this, the Government of India can seed a reimagined way of managing data - which ensures that communities collect, manage and use their data making the primary objective of these programs i.e. to be participatory, a reality.