Summers get hotter, rains decline and crops fail. The conflict between people increase and migration in search of better lands and skies begin. Sounds familiar? We are not talking about Marathwada here. This is how the lives of our ancestors played out thousands of years ago. The Harappan or the Indus Valley Civilisation experienced climate change, but they responded better to it than we are doing now, says a new study by Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagur, published in Nature recently.

For long, foreign invasions, social instabilities and decline in the trade have been flagged as reasons for the decline of this ancient civilisation. But now, it seems, climate change, spread over 5,000 years, too, played a decisive role. In a way, history is repeating itself except that what is happening today is a man-made catastrophe. The exact cause of the decline in rains and aridification in ancient India is not yet clear. What’s certain, however, is that migration and shift to hardy crops saved the day for our ancestors. And that is the best Rosetta Stone we have stumbled upon so far.

How it could have been

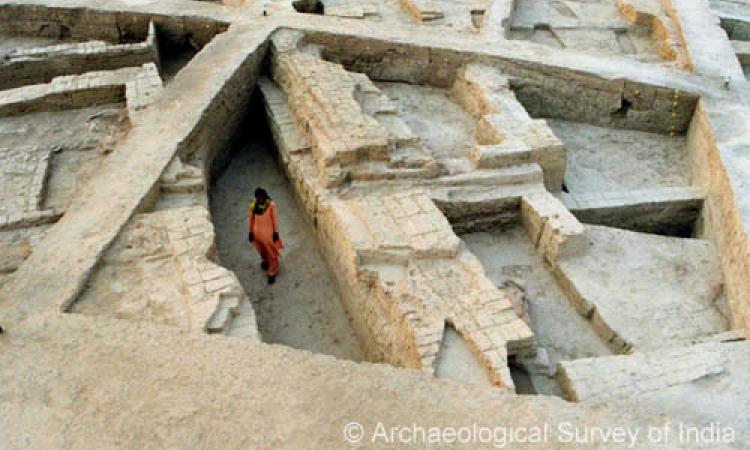

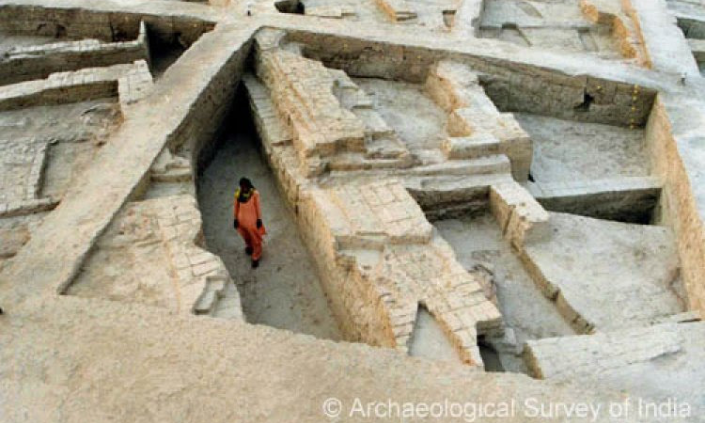

Scientists and archaeologists have found a site at Bhirrana village on the bank of Ghaggar river in the present-day Haryana which is probably older than other Harappan sites, stretching way back to over 8,000 years. “This site is important because it preserves four cultural levels of the civilisation starting from pre-Harappan to mature Harappan periods, a time span of 6,700 years. Only the late Harappan level is not present. It’s rare to find so many cultural levels at one site,” says Prof. Anindya Sarkar, head of the department of geology and geophysics, IIT Kharagpur, who authored the study.

Another interesting finding of the study is that monsoon was the reason for the flourishing and the decline of this civilisation.

It is not possible to go back in time to see what climates were like. So, scientists generally use proxies like fossils trapped in the sea and lake beds or in the soil. Bhirrana provided a new opportunity. “We found large quantities of animal bones and teeth which could be studied. This had never been done earlier to study weather in ancient India,” says Dr Arati Deshpande Mukherjee, assistant professor at Deccan College, who analysed these samples.

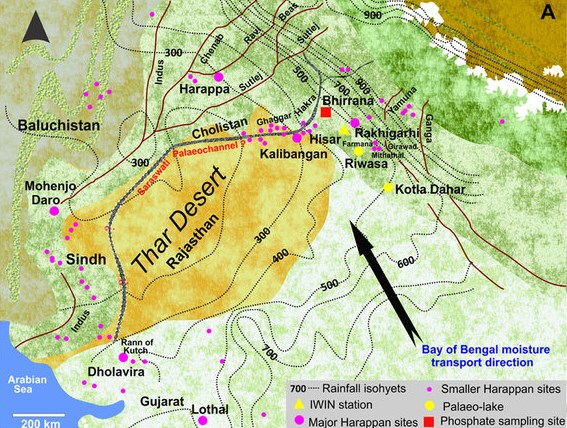

Over the years, several studies have tried to map the ancient weather and agreed on this timeline. The Indian monsoon was weak till 9,000 years back due to which people might have indulged only in small farming and pastoralism. Later, the rains intensified, feeding the Ghaggar-Hakra rivers, which supported intensive agriculture on their floodplains--starting from the present-day Haryana through Rajasthan, the desert region of Cholistan and Sindh (both in Pakistan now) and emptying into the Arabian Sea through Gujarat. This is the stretch where the remains of many ancient habitations have been excavated.

Researchers believe that better farm production would have led to the flourishing of the civilisation through well-planned urban settlements like Bhirrana, Harappa and Mohenjo Daro (in Pakistan) and Lothal (in Gujarat). Farming and trade with other civilisations, including Mesopotamia, were the main occupation. The cities also had large, centralised grain storage systems to meet the high demand and also, as buffer for shortage.

However, monsoon started declining again around 7,000 years ago and a harsh drought ensued 4,000 years ago leaving even large rivers dry. Similar aridification occurred around the world at the same time which, perhaps, led to the collapse of the old kingdom in Egypt, the early bronze age civilisations of Greece and Crete and the Akkadian empire in Mesopotamia. Tibet, Mongolia and China also saw extended droughts.

How they dug, what they found

Researchers from The University of Cambridge examined snail shells from two ancient lakes--Riwasa and Kotla Dahar--in the present-day Haryana. These fossil shells were checked for levels of O-18, an isotope of oxygen which is an indicator of warm water and increased evaporation. The concentration of O-18 was found to consistently increase as the age of fossils reduced. This proved that the monsoon declined over the years.

The then annual rainfall, scientists say, was similar to what the north-west India gets now in non-monsoonal months. Such a drastic drop in rainfall, persisting for several years, had the ability to transform landscapes.

Scientists found similar results from the floor of the Arabian Sea. Every year, strong monsoon winds churn up the Arabian Sea making cool water to rise to the surface from its depths. This movement is called upwelling and the cool water results in the blooming of Globigerina bulloides, a plankton, which is usually absent in this region. Scientists retrieved the bulloides from the sea floor sediments and found reduction in their strength over the years. This signifies that the Arabian Sea upwelling had weakened, probably due to failing monsoon.

The latest study by IIT Kharagpur employed a new method. For the first time, the scientists have studied the teeth and bones of animals found from the excavated site. This is an improvement on the earlier studies done in distant lakes and sea floor, which could have been impacted by local factors, besides rain or temperature.

“The level of O-18 isotope in mammalian tooth enamel and bones depends on the level of O-18 in water the animals drank. The samples gave out results which matched the previous studies,” says Dr Mukherjee.

How people adapted

What a declining monsoon might have done to the urbanised settlements can be imagined. The river flow declined and Ghaggar-Hakra could have become seasonal or gone completely dry. Still, people tried to adapt. They did the next best thing to deal with less rain: crop diversification.

Though Bhirrana site did not yield any crop-related information, around 100 km away at Farmana village, the researchers had earlier mined evidence of starch grains from excavated pots, burial grounds, grinders, pounders, stone blades, sediments and the human teeth from burial sites.

The study found dramatic decrease in the availability and the seed density of wheat and barley in the later Harappan period (3850-3250 years ago) as compared to the early and mature Harappan periods (5250-3850 years ago).

The archaeologists not only noticed a decline in seed crops but also a shift in cropping--from a winter-based strategy to the one equally dependent on both the seasons . Millets and rice are significant summer, rain-fed cereals in contrast to wheat and barley which germinate during winter and spring.

This shift towards small-grained millets with much lower yields, however, might have sounded the death knell for urban habitations because they couldn’t sustain on them. “The large grain silos, which we found in earlier periods, were not present later. This might have given way to individual household-based crop processing and storage,” says Prof. Sarkar.

Previous studies indicate that this shift could also have impacted the economic foundation of cities run on revenue collection from central acquisition, storage and distribution of grains. At the same time, the west Asian trading partners like Mesopotamia were dealing with severe drought as well, further weakening the urban economy.

The study also indicates increasing dependence on summer crops like millet, which are well known drought-resistant crops. Millets are still recommended by experts as the best bet for drought-hit areas.

Our ancestors dealt with these drastic changes through migration to the rural areas, while many cities continued with reduced population. Smaller, rural settlements increased, especially in the Himalayan foothills, along the Yamuna river and between the courses of Yamuna and Ganga.

These findings remind us of the current climate change scenario which is estimated to impact the global economy to the tune of $60 trillion, most of which will be borne by developing countries with extreme weather, poorer health and lower agriculture production plaguing them.

According to various estimates, 161 countries have witnessed mass displacement of people due to weather-related events since 2008. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) says 36 million people were displaced by natural disasters in 2009. The number is estimated to rise to 50 million by 2050. As evident during the Syrian and Nigerian crises, shortage of resources often leads to increased conflict where armed groups take advantage of the prevailing resentments due to droughts.

In fact, the drought that preceded the rebellion in Syria is considered the worst long-term drought and the most severe set of crop failures since the agricultural civilisation began in the region. The unrest and the violence against migrants in Europe are samples of what the future holds for us.

Change leads to violence

Inter-personal violence were believed to have increased in Harappa, one of the biggest urban centres of Indus civilisation, during the period of social transformation due to migration. Scientists have also found assault injuries on skeletons excavated from the burial sites, suggesting that the stress of dramatic, rapid social change and uneven access to resources may have led to conflicts and violent incidents.

The current refugee crisis in Europe can be seen as a re-run of sorts. And such mass migrations are expected to increase in the future.

Dr Gwen Robbins Schug, who studied these burial remains, says evidences of infectious diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis were also found besides significant micronutrient deficiencies in urban areas. “The subsistence system became increasingly deranged over time that even pregnant women were unable to meet their basic nutritional requirements. Thus, it appears that the decision to stay behind in settlements (urban) that had largely been abandoned, had profound consequences with regard to the health and well-being,” she adds.

Today, we see the impact of climate change more profoundly on the most vulnerable, the poor. Similar was the case in Harappa. “Women and those found in marginalised burial areas were more likely to face these hazards when social control mechanisms and centralisation fall apart,” Dr Schug says. Thankfully, the violence has not been found widespread. Not yet. “There is evidence for some interpersonal violence at Kalibangan and Mohanjo Daro sites but former is yet to be studied systematically and the origin of latter’s remains and the circumstances in which they were found are questionable,” Dr Schug says.

What we learn is up to us

So, even if we blame the climate change for several misgivings, how we adapt to the changing skies holds the key to a thriving civilisation.

“There is so much we do not know about the Indus civilisation and there is so much potential to gather information that may be pertinent to issues we face today but there must be governmental, institutional, and academic support for freedom of inquiry,” infers Dr Schug.

Prof. Sarkar believes the best thing about this ancient civilisation is their resilient and participatory society. “They persisted for thousands of years without technology which could have only been possible through brainstorming and joining the forces. Today, I can’t imagine our seemingly advanced habitations surviving for more than 200 years if they are hit by a similarly harsh climate. It’s time we take lessons from history,” he adds.