“The gravity of the Kedarnath disaster in June 2013, which killed thousands of people, shocked the public almost to the point of numbness”... begins the forward by Bill Aitken in Hridayesh Joshi’s account of the disaster Rage of the river: The untold story of the Kedarnath disaster. It’s a sentence which will whirl in your mind while you read Joshi’s book. This is an English translation of a book originally published in Hindi titled Tum Chup Kyon Rahe Kedar. Aitken, a Scottish-born, naturalised Indian travel writer and mountaineer and author of The Nanda devi affair warns that a massive earthquake was predicted in Uttarakhand which was long overdue. “The moral of the Kedarnath disaster is to think ahead and plan for the next big upheaval,” he adds in the foreword.

The world remembers June 16 and 17, 2013 as the days when river Mandakini spawned a disaster in devbhoomi (land of gods), Uttarakhand. As if possessed by the impulse of a wild being, the river crushed everything that came in its way. With casualties going up to the official figure of 5000, the aftermath was overwhelming. The usually calm river wiped out everything in its path-- houses, bridges, dams, towns like Rambara and Kedarnath. Decomposing bodies and skeletons can be found there to this day. The local economy has been ruined and lakhs of people lost their livelihood. Government’s relief struggled to reach rural areas and provide adequate aid for survivors.

Failed administrative machinery

Joshi is an NDTV journalist who covered the Uttarakhand flood of 2013 extensively. He, along with his colleague Siddharth Pande, was one of the first few to expose the government’s indifference and incompetence in dealing with the aftermath. He brought survival stories of people who endured the river's fury by clinging on to trees and that of valour, generosity and warmth of local people in the most trying circumstances.

Rage of the river shows how the administrative machinery was clueless about the deluge. Though triggered by a cloudburst, the disaster was in the making for days because of the heavy rain. At the peak of the tourist season of Kedarnath yatra, people were stranded at great heights. Not many could survive for days without food and water and perished.

The government’s denial in the face of the nature’s fury where countless people were either swept away by the river or buried under the debris was heartrending. A deathly silence prevailed over the valley as commercial helicopters hovered over it doing sorties and creating helipads to rescue thousands of people. The trainees and staff of the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering too worked heroically during the rescue mission. This was well before the army or the National Disaster Response Force came into action. Joshi brings out some harrowing tales, like that of an elderly person, when approached, choked with emotion initially but gathered the courage to say, “12 of my family members were swept away. My relatives, friends, children, wife…all are gone, I have no one left”.

“One of the most disillusioning aspects of the tragedy was that in this hour of need, the administration was missing or proved to be thoroughly incompetent,” Joshi adds. This journalistic overview replete with environmental and historical aspects of the disaster stresses that many more lives could have been saved had the government not been lax. Also from the evidence Joshi provides of how the rehabilitation work is progressing it is hard to see this story turning out well.

Who dug the grave?

The chapter, Who dug the grave?, deals with the human recklessness that had taken place in the name of "development" through the decades. Rivers were clogged, slopes were ravaged by commercial logging, dams destroying the riverine ecology and roads built by blasting the hills. Building norms were flouted and illegal encroachments by the powerful hotel and construction lobby right next to the river added to the risk. As Aitken puts it, “Instead of judicious development of the world’s highest and steadily rising mountain range, shortsighted and unsustainable development was resorted to.”

The text offers a sociocultural perspective, especially as the book moves backward in time to the colonial times when Uttarakhand experienced movements against the British forest laws that alienated the local population. The history of the hill’s people’s resistance movements like the Chipko Andolan and the Tehri dam agitation against alienation from natural resources is also traced in a chapter.

Through his grounded, well-researched analysis, the author captures corporate greed when he documents the unnerving case of how Jaypee group officials ignored the rise of water level in the Vishnuprayag dam even when the villagers brought it to their attention on June 13, 2013. Commercial interests prevailed and the gates of the dam were not opened to let the excess water flow safely downstream. This led to villages being swept away, leaving a trail of devastation behind in the days to follow. Moving on the realm of policies, Joshi notes that the government of Uttarakhand has “no specific policy for development and planned construction keeping the environmental issues in mind”.

The last chapter ends with a prescription for model growth which includes measures such as saving the forests, saying no to large dams, shifting to micro and mini projects, more solar energy, well planned road construction, sustainable farming, greater role of women in decision making, diversifying tourism, waste management, curbing pollution, ban on plastic and a green tax for visitors.

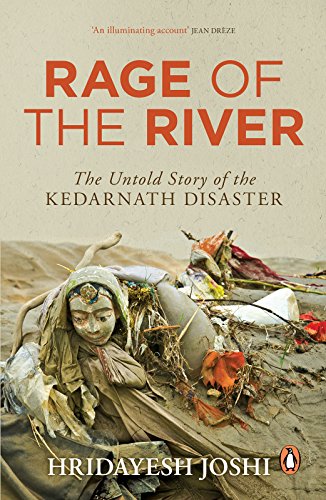

The book’s text is illustrated with several photographs of the calamity, the people and the efforts. The lucid and authoritative analysis of the floods will be of interest to environmentalists, planners and administrators of disaster-preparedness programmes. The blow-by-blow analysis of the response and recovery effort during the floods keep the narrative tight.