South India has a rich tradition of tanks with the three southern states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh contributing to close to 92% of the total irrigation by tanks in the 1970s. Two decades later, this number dwindled to close to 53%. A decade after that, in 2001, the total contribution of tank irrigation in all of India was estimated to be just around 5.18%. In stark contrast, other sources of irrigation such as borewells and tubewells have clocked consistent increase in percentage use. (Source: Indian Agricultural Statistics 1985-86 - 1989-90, Vol-I, Ministry of Agriculture, GoI, New Delhi)

Tanks of Tamilnadu

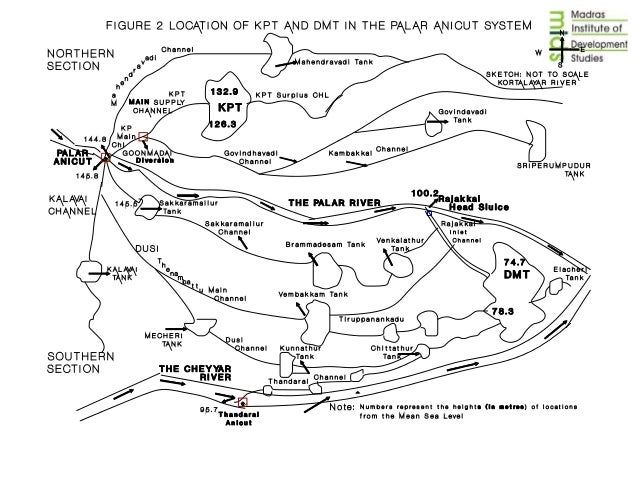

Tamil Nadu has no perennial rivers, they are all fed by the monsoons. These rivers have to cross state boundaries before they irrigate the fields downstream. Several hundred years ago, a system was devised to utilize the water flowing in the rivers to the fullest before it reached the sea. It was a simple act of engineering that diverted the river water into tanks through dug out earthen channels, which in turn took care of the irrigation needs of neighbouring villages.

While it was easy to divert water to nearby villages, it wasn't that simple to connect those that were far away from the source. Engineers devised a simple solution- a series of cascading tanks. The outflow from one tank would serve as the inflow for the next one in the series since the tanks were designed to allow the excess water to flow out after it has reached its capacity. The thought and effort put into designing these massive chains of receptacles and over-flow channels hundreds of years back is awe-inspiring.

No concrete, no hi-tech machinery; all mud and man power.

The sytem and the non-system eris and their ayacuts

Eris are of two types – system and non-system eris. System eris are those which are fed by streams of rivers through a channel, while the non-system ones are stand-alone isolated tanks fed by rain. Most of the tanks in Tamil Nadu are system eris.

The extent of the eri’s ‘ayacut’, which is the area that is irrigated by a particular tank, determines the way in which it is governed. For example, if the water from the tank irrigates 100 acres of land around it, then the tank’s 'ayacut' is said to be 100 acres. If the 'ayacut' is over 100 acres, the tank is categorized as a ‘PWD Tank’, where the Public Works Department of the state is responsible for its maintenance and upkeep. If it is less than 100 acres, then tank is a designated Union/Block-level tank managed by the local Panchayat.

The neerkatti's role

Conceptualizing and constructing these structures is one thing but to keep them viable in the long term is another altogether because that completely dependens on the way they are maintained and managed. Since village life is centred on water and agriculture, the importance of keeping these structures well-oiled was not lost on the community. Ways were devised to retain the incoming water based on the requirement of the village and the excess was allowed to flow into the next tank in the series.

A dedicated person called the ‘neerkatti’ kept a close watch on the water level and was in charge of channelling this water to individual fields. Villagers showed their gratitude by sharing a part of their bounty with him. The entire village got together to perform repair and maintenance work – called ‘kudimaramathu’ to keep all the physical structures intact.

But everything changed with the entry of the British. From the knowledgable ‘neerkatti’ and a concerned community, the management of these tanks went to a centralised channel-the Public Works Department.

DHAN Foundation has been working to bring back community participation and ownership for over two decades. They have invested a great deal of time and energy in bringing the community together to organize themselves into groups called ‘vayalagams’ to manage their village tanks and ponds in an efficient and sustainable manner.

Kanchipuram: leader in tank irrigation

Kanchipuram has a total of 1942 tanks irrigating over 60,000 hectares of farmland in the district. Here, tank irrigation still leads the chart, but it may not retain the top spot for too long since individual irrigation sources like borewells and tubewells are catching up. After Pudukottai, Kanchipuram is the chart leader when it comes to utilizing non-system tanks for irrigation in the state.

DHAN’s Technical Co-ordinator Prakash is tasked with visiting some of the organization’s project sites in and around Acharapakkam in Kanchipuram, which includes Thirukazhukundram, Lathur and some areas in Villupuram. He explains that earlier the Vaylagams were Panchayat-based. Later they were split into village Vayalagams for the sake of convenience in managing daily affairs.

How does a vayalagam function?

A Vayalagam consists of a general body and an executive council. The former is made up of 50-60 villagers based on the strength of the village while the latter is a more compact group mainly involved in day to day administration and decision making. In order to prevent the Vayalagam President from taking autocratic decisions, two more leaders are taken on board to assist him. One is the elected Panchayat leader while the other is a respected village elder or ‘nattamai’ chosen by the people.

Thalambedu Tank association is one of the oldest functioning vayalagams in the Thirukazhundram block of Kanchipuram. Its current President Kanniappan has been at the helm of affairs for over a decade now.

When the vayalagam was started in 2000, people from the village got together to clean up the Thezhappanthangal eri, the first in the open catchment cascading sequence. The association collected money from the ‘Ayacutdhaar’ (Ayacut farmers) to kick start the work at Rs. 3/ cent (1 Cent is close to 435 sq. ft.) of a farmer’s holdings. Few kilometres away, the Pulleri Tank Association also adopted a similar approach when they first started out. The contribution was not restricted just to money. Villagers pitched in with their ploughing and clearing skills as well.

Their main job is to make sure the tank is fit in all ways to supply water for the irrigation needs of the 280 acre strong ayacut. Physical maintenance includes desilting the tank to make sure the holding capacity does not decrease with its age due to siltation, strengthening of bunds to prevent the earthen banks from giving way during floods and the regular maintenance of the ‘madhagu’ (sluices ) and the ‘kalangal’ (surplus weir through which excess water is let out).

Finances and the vayalagams

The economic independence and viability of the tank association is ensured by providing the associations with a corpus fund deposited in a common bank account over which they have full control. The vayalagams are free to manage their money the way they want, but one rule is non-negotiable -the associations are not to spend the corpus fund under any circumstance. The interest accruing out of the initial corpus is used up for all repair and maintenance work and the corpus itself is expected to remain unspent.

Cash flow for the vayalagams does not stop at just interests from the corpus. Kanniappan mentions that the local Panchayat shares part of its income from leasing out the common land around the tank for growing of tamarind and other commercially useful trees with the association. If an outsider is interested in taking the silt from the tank for his field, the Vayalagam makes sure to collect the toll before his bullock cart leaves the village. Apart from this, they also collect small amounts from individual farmers based on the needs. This contribution, however, is kept mostly voluntary.

After close to 13 years since its inception, the Thalambedu Vayalagam now boasts of a savings of close to Rs. 60,000, which includes the initial endowment of Rs. 30,000 from Sir Ratan Tata Trust and the Vayalagam corpus of Rs. 30,000.

Project Ooranis

While eris irrigate fields, ooranis provide drinking water. Ooranis are usually smaller and shallower than eris . These tanks are dug out to catch the rainwater and store them up for later use. Water from the ooranis remain the most preferred choice for drinking in many villages in Tamilnadu.

DHAN has been working with individuals and organizations to renovate ooranis which have gone into disuse. It had partnered with the Government of Tamil Nadu and Anna University, Chennai to rejuvenate ooranis under the integrated rainwater harvesting programme. Ooranis in Pattikadu and Edaiyur were renovated under this scheme.

The Madras Atomic Power Station (MAPS) as part of its Corporate Social Responsibility initiative has sponsored the renovation of an oorani in Nallur village close to its home base Kalpakkam. Desilting of the existing oorani is underway in the village. Locals are involved at all stages, including planning, executing and monitoring.

Vayalagams vs. Micro Finance and Self Help Groups

DHAN had actively played a role in introducing Micro Finance Groups (MFG) in this region from 2004. These groups played a vital role in increasing the amount of liquid cash available for members in times of need. Loans were disbursed to interested villages to form these institutions after making necessary provisions for interest generation and loan repayment. Thalambedu village also has a successfully functioning MFG which has over Rs. 4 lakh stacked up under its name after repaying the initial loan amount.

Apart from mobilizing funds, these MFGs also promote the concept of insurance and savings. Many farmers have now availed services of Insurance Corporations, both for their life as well as crops. Kanniappan immediately recalls the case of farmer Chellappan. After his death, the insurance money helped Chelappan’s family get by till their affairs stabilized.

Members of tank associations in Thirukazhukundram block feel that the importance of the ‘Eri sangam’ or the tank federations is diminishing quickly. They attribute this to the phenomenal growth of the ‘Self-Help Group’ system. Villagers actively partake in SHG activities than that of the tank associations as the fund mobilization is much more in SHGs. Yet, ayacut farmers have managed to stay together to protect their symbiotic relationship with each other and their water sources.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Mr. Prakash for taking the author around to all the villages mentioned in the article and more in Thirukazhukundram block and to Ganesan for driving the author in and around Kanchipuram. Special thanks to Mr. A. Gurunathan, CEO of DHAN Vayalagam (Tank) Foundation for all his help and support, without which this field trip would not have been possible.

References