The state of Rajasthan has an immense range of ancient and ingenious water harvesting systems, like the famous johads or step wells managed by communities in the arid Thar desert, which receives very low rainfall. A recent book 'Wise water solutions in Rajasthan' by Om Prakash Sharma, Mark Everard and Deep Narayan Pandey documents the enormous array of water harvesting systems, that have survived the test of time and are still in use.

Communities continue to access and efficiently use the waters from these time-tested water harvesting systems across the state’s villages and towns. The authors, who have worked in the field of environment and water conservation for several decades, put this book together to help communities identify geographically and culturally context-specific water harvesting solutions to suit their unique needs.

The book underlines the need to achieve the most optimal results by using local knowledge about the myriad, well-organised ways in which communities managed water traditionally. Dr. Nicholas Grey and Professor Mary Grey, Honorary Presidents and Founders of WaterHarvest, mention in the foreword to the book that the water harvesting structures documented in the book are optimal according to slope, soil structure, and the village's needs.

“In the Aravalli hills the focus is to hold back rainwater flow to allow it to percolate into the ground and thus recharge the well. In the Thar desert where the water percolates straight through the sandy soil and is lost, the focus must be on water storage.”

Demonstrating the effectiveness of water harvesting systems

These traditional practices and their modern adaptations have often helped people tide over periods of drought.

Differing based on the region’s physiography, hydrogeology, rainfall and culture, these small-scale systems offer decentralized water access to water.

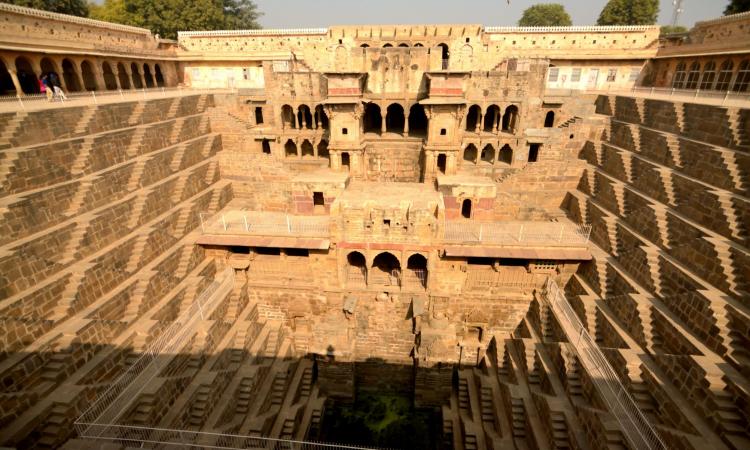

Section 3 of the book, ‘Water wise solutions’ details how specific solutions are adapted to local conditions, including their design and maintenance aspects. Both, surface water systems (such as talaabs including large lakes / sagars and small naadis / naadas) and groundwater access and recharge systems (wells, taankas, kunds, baodis, johads etc) have been documented here. Notes are presented on each system including directions on construction and management requirements. A matrix maps each purpose (primary or secondary) of each solution, further categorising them into harvesting/recharge, access and use efficiency.

“The book documents modern solutions to harvest and improve use efficiencies and argues that ancient solutions alone may not be sufficient. The challenge is to integrate and perhaps develop further traditional structures with modern solutions,” says Om Prakash Sharma, one of the co-authors of the book.

The book also features a recent innovation in the form of ramp wells that provide year-round access to water for wildlife in the Kumbhalgarh sanctuary in Udaipur, Rajasthan. The ramp has a gentle slope so that wildlife of all sizes can easily access the water in the well or sump.

There are also various adaptations of modern rooftop rainwater harvesting systems in rural and urban areas of Rajasthan for recharging groundwater, which are thereafter accessed through open wells and tubewells. Factors considered in their installation include the availability of suitable roof catchments, soil foundation characteristics near the house, location of overhanging trees over the roof and the availability of construction material. In the desert regions of Rajasthan, some households have integrated rooftop rainwater harvesting systems with taankas, with the roof replacing or augmenting artificial catchments to fill the underground taanka.

The book outlines the governance arrangements behind the design, operation and maintenance of these systems. “Before the onset of the annual monsoon, naadi, tank beneficiaries would clean the agor (catchment) serving it. The system of water distribution took into account the water demand - the number of humans, cattle and goats. Payments were made in the form of cash, kind as well as voluntary labour. Upstream users were prohibited from planting water intensive crops while for direct beneficiaries water intensive crops were rotated from year to year. Penalties were imposed for violation of rotational irrigation arrangements,” says Sharma.

The book also touches on individual and collective accountability within the community. “Every person could hold a certain amount of land within the irrigable area, with additional landholdings entitled to less water. Policing was achieved at the community level, through sometimes also using guards and other enforcement arrangements. Water managers were sometimes drawn from the landless class.”

This book is a valuable guide to anyone working on water harvesting in Rajasthan. It has a lot of pictures, diagrams and tables to help understand the basics and to get started on designing water harvesting systems.

Click here to download a few pages of the book.