Tenzing Lepcha, the lead activist of Affected Citizens of Teesta (ACT), is proud of his work in the last year. “All this was overgrown,” he says pointing at the orderly farm. “I created the fields myself.” He shows us the carefully dug out pond for water storage, the irrigation system, the compost heaps, the neatly staked peas and rows of mustard. It is difficult to recognise him now, my earlier image of him being that of a listless young Tenzing, weak from fasting for months.

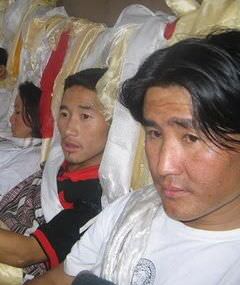

Tenzing, Gyaatso and Dawa are among those who had gone on a relay hunger strike from the year 2007-2009 demanding withdrawal of the hydroelectric projects in the Dzongu region. The hunger strike lasted for more than 150 days. Tenzing recollects how he had first joined the movement. He says, “We attended a meeting that opened our eyes to these dam issues. I attended my first public hearing on September 18, 2005. It was against the Panang project in Dzongu and I got arrested. I was also there with Dawa for the hunger strike. It was in two phases--in the first phase, we fasted for 64 days and in the second phase, for 96 days.”

This hunger strike, as well as the other protest marches, numerous petitions and presentations organised by the ACT succeeded in drawing national and global attention to the issue of dams on the Teesta. As a result of this struggle, the ACT was able to press for the first study investigating the carrying capacity of a river basin in India. As a result of this report and the protests, 10 dams were cancelled.

However, the people’s struggles did not end with the calling off the hunger strike. Two of the dams being planned are located in the Dzongu area, and people are mobilising to stop those dams.

Development is possible without dams In addition to protests, the ACT members feel the need to demonstrate to people that development is possible without dams. Some of them lead by example and demonstrate alternative livelihoods that will bring in economic progress. This is in line with the philosophy of the late Shankar Guha Niyogi, the leader of the Chattisgarh Mukti Morcha which was established in the 70s. In his last article, ‘Our environment’, Niyogi had stated that struggle and reconstruction must go hand-in-hand. He wrote, “Wherever there is injustice and oppression, there is bound to be resistance. The process of destruction can be countered by the creativity of construction”. His slogan of “Sangarsh Va Nirmaan”--struggle and construction--inspired a whole generation of activists and movements in the 80s and 90s.

In addition to protests, the ACT members feel the need to demonstrate to people that development is possible without dams. Some of them lead by example and demonstrate alternative livelihoods that will bring in economic progress. This is in line with the philosophy of the late Shankar Guha Niyogi, the leader of the Chattisgarh Mukti Morcha which was established in the 70s. In his last article, ‘Our environment’, Niyogi had stated that struggle and reconstruction must go hand-in-hand. He wrote, “Wherever there is injustice and oppression, there is bound to be resistance. The process of destruction can be countered by the creativity of construction”. His slogan of “Sangarsh Va Nirmaan”--struggle and construction--inspired a whole generation of activists and movements in the 80s and 90s.

Gyaatso Lepcha, the secretary of the ACT runs a charming and successful homestay, Mayal Lyang. Gyaatso says, “A lawyer by profession, I was practising for a while till I got involved in activism. My homestay is more of a silent protest against the state’s idea of bringing devastating projects to an ecologically fragile and culturally important region like this. It is a different way of saying ‘hey, this will also bring development without the ecological, cultural and human cost’.”

This homestay at Passingdang village in Dzongu shot to fame when the crown prince and princess of Norway vacationed there. The homestay finds mention in the CAG report on Sikkim and has spearheaded state interest in promoting homestays as a means of sustainable tourism in Sikkim.

Farming too is profitable

Tenzing has gone back to his farming roots. He says, “The more close you are to the soil, the better the attachment to it. My efforts in agriculture will also motivate others (to take it up).” Tenzing’s decision to start farming is also related to the protest against hydropower. He explains, “When they (the government) use the term ‘economic development’ it should not mean hydropower only. We are very lucky to have all this landscape. We have a lot of alternatives. Now see the Sikkim government has declared the state organic. We do have the potential. So, it is high time for the government to also tap those potentials for the future generations.”

Minket Lepcha had settled down in Delhi when Gyaatso informed her about the struggles going on in Dzongu. Now, Minket is also part of the movement and uses her art to showcase the beauty and values of Dzongu so that people outside the valley have a glimpse of all that may be lost to dams. Minket’s movie on the issue also helped convince pro-dam people within the valley. She says, “This is the only film that links the upstream and downstream people. When I mentioned that the Teesta is like a spine for the communities along the river, I could see acceptance in people’s eyes.” Minket’s film, Voices of Teesta, became one of the 10 films screened at the just concluded eighth World Water Forum in Brazil.

Like Minket, Dawa Lepcha too is making films set in Dzongu. He began his career making ethnographic documentaries that described the Lepcha way of life. One of his documentaries, Ritual Journeys records the everyday life of Meyrak, a Bonthing (a holy man) over a period of seven years. More recently, Dawa made the first Lepcha feature film, Dhokbu-the keeper. In an interview with The Darjeeling Chronicle, he says, “Like every tribal community around the globe, we Lepchas also believe in natural deities and protectors of wild forest and wilderness. This film is about a mythical character who is the guardian of the wilderness in Sikkim Himalayas. The film reflects some of my thoughts influenced by my days of intense activism.”

Spreading the news far and wide

Keeping a peoples’ movement alive for more than a decade takes an incredible amount of work. Public activities such as protest meetings and marches, sit-ins and hunger strikes, press statements and open letters are merely the tip of the iceberg. Far more relentless and exhausting is the quiet work of ceaselessly keeping up-to-date with government activities and decisions, collating documents and evidence, maintaining contact with supporters and extending friendship towards dissenters.

They don’t shy away from engaging people from outside Dzongu on the topic of hydropower in Sikkim, either. Gyaatso says, “I make sure the guests who come here attend one session where we talk of dams. I show them a documentary and then the conversation opens up.”

Besides hydropower, they also engage with other issues in the region. Gyaatso organised a meeting of Panchayat presidents to talk about waste and consider zero-waste solutions for Dzongu. Minket travels the country telling stories and showing her film and is trying to engage especially with school children on environmental issues.

Reflecting on his decision to explore alternatives, Gyaatso mirrors Niyogi’s philosophy. “I realised that activists are always looked at as anti-development by both the state and by people. In my small way, I wanted to change that. To some extent, a lot of those allegations are true. People have aspirations. This is Dzongu, what other opportunities are there? People need jobs and other things. This is where I thought, when we do activism, we should not just protest or go around resisting things. We should also start coming up with new ideas, showing alternatives (to livelihood).” To put it in the words of the Italian philosopher, Antonio Gramsci, the activists are creating “counter hegemonies” of the people.

The field trip for this article has been funded by the CCMCC-NWO project, “Hydropower development in the context of climate change: Exploring conflicts and fostering cooperation across scales and boundaries in the Eastern Himalayas