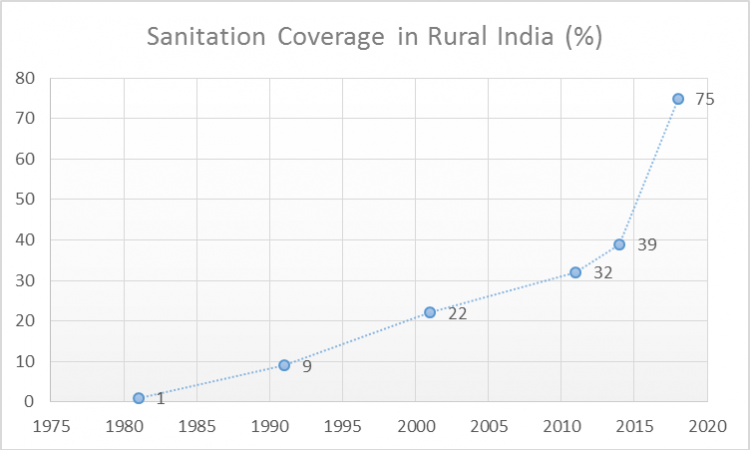

Rural India’s tryst with toilets began with its first sanitation programme--the CRSP (Community Rural Sanitation Programme) in 1981, when the country’s rural sanitation coverage was a mere one percent. By 2014, it was 39 percent, i.e., an average of about one percent increase in sanitation coverage per year. The year 2014 saw the launch of the Swachh Bharat Mission Gramin (SBM(G)) which aimed to create an open defecation-free (ODF) India, by providing access to toilets for all.

As we step into 2018, rural India’s sanitation coverage stands at 75 percent--an increase of 36 percent in a little over three years. While six crore new households being provided access to sanitation at such an accelerated pace is reason enough to celebrate, at the grassroots, some unlikely heroes have emerged as the champions of this people’s movement. Women, children, senior citizens, economically- and socially-backward communities are leading the way to a Swachh Bharat in the hinterlands of India. The role of women has, in particular, transformed tremendously since the launch of the mission, and it is instructive to analyse how and why.

Toilets for women

Toilets are arguably one of the most potent tools of women empowerment in history. A 2012 National Bureau of Economic Research paper states, “There was no more important event that liberated women more than the invention of running water and indoor plumbing.” A 2017 Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation study found that there were significantly higher cases of women with lower Body Mass Index in non-ODF areas than in ODF (Open Defecation Free) areas, indicating disproportionate impact of lack of sanitation on women’s health. At the same time, a 2017 IMF research study found that an improvement in public sanitation reduces women’s time spent in caregiving work by 10 percent, and leads to a 1.5 percent increase in female labour participation.

Sanitation also leads to high female literacy rate. There are innumerable examples and studies that establish the role of toilets as the unlikely feminist champion in the women’s empowerment movement. But perhaps the best byproduct of Swachh Bharat for women is the shift in perceiving women as leaders and not as victims.

Dignity first

One might recall a recent advertisement, featuring actor Vidya Balan, by Nirmal Bharat Abhiyaan. In the advertisement, she is seen advocating that a new bride be given a toilet, else her ghoonghat would do nothing to preserve her dignity. The message was: “Build a toilet for the woman to protect your family honour.” The ad was, sadly, mute on the regressive ghoonghat practice itself. This is deeply problematic and acutely reflective of the prevalent narrative at the time--advocating toilets, while inadvertently reinforcing toxic patriarchal notions, such as, “women’s bodies are the property of her husband or family”, “man is the protector of the woman”, and “woman is the receptacle of family honour”. It was no surprise that this myopic messaging proved counterproductive in the long run.

Men around the country were found refusing to use toilets because of the belief that using a toilet is for women and open defecation, by extension, a sign of virility. On the other hand, women’s groups were seen rallying against toilets, seen as a threat to their freedom to leave the house at least once a day. Under SBM(G), the 2016 Gender Guidelines emphasised the need for gender sensitive messaging for sanitation. Following this, the mission launched a national level mass media campaign--Darwaza Band--that led by example. Several advertisements under this campaign feature eminent actor Amitabh Bachchan where he is seen coaxing and cajoling men to not only build toilets but also use them. The second part of the campaign, featuring actor Anushka Sharma, calls upon women to play a leadership role in promoting toilet use in their homes and villages, and celebrates their collective and individual strength as changemakers. This message, in particular, is a breath of fresh air compared to the traditional narrative of women as powerless victims, at the mercy of their men and families.

At the community level, the SBM(G) Gender Guidelines also direct that “women should be represented in the leadership of SBM(G) committees and institutions… so that their communities and villages can benefit not just from women’s participation but also their leadership”. The result of these highly progressive directives is that Swachh Bharat has seen women of rural India transform in their role from victims to leaders. Women are seen taking up traditionally unconventional roles, like masons and contractors engaged in toilet construction. Many are also becoming Swachhagrahis who deliver the behaviour change communication to the community and earn an incentive for every toilet they help construct. Villages headed by women sarpanches are empirically found to be more likely to achieve and sustain ODF status.

Naari shakti, swachh shakti

Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, rang in the International Women’s Day 2017 with 6000 women sarpanches under the banner, “Swachh Shakti”. Their stories offer a glimpse into the role women are playing for sanitation in rural India. Asha is a mason, working in a male-dominated profession and building toilets in a patriarchal community of Rajasthan. Akamma, from Karnataka, mortgaged her jewellery to construct a toilet for herself and those around her. Chhattisgarh sarpanch Uttara Thakur, undeterred by her own physical handicap, led her village to become ODF. Sushila Kurkutte, a tribal woman from Maharashtra, dug a toilet pit by herself so that her family would have access to safe sanitation.

As India rings in 2018 with 300 ODF districts and three lakh ODF villages, these “Swachh Shakti” icons are at the forefront of the sanitation revolution happening in the country. And India’s sanitation revolution is, in turn, the biggest and the most effective feminist movement silently underway in the country today.

The author is a project manager, water and sanitation team, Tata Trusts.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of India Water Portal.