History tells us cities were settled and abandoned several times in Delhi. But I have not come across an explanation for why the city was repeatedly established at the same site. Surely, the presence of the river Yamuna to the east of Delhi would have been a reason. The Yamuna, though is not a small river; it flows for 1,300 km. Once an old city had been abandoned, why weren’t the new cities of Delhi established upstream or downstream of this location?

Perhaps a major reason for that is the presence to the west of the river of the Aravalli mountain range. From the north to the south of Delhi, it provides a kind of protection that was unavailable elsewhere along the river. And at least 18 tributaries ran from the Aravalli to the Yamuna, flowing right through Delhi from the North to the South. Hence Delhi was going to settle here itself after every abandonment.

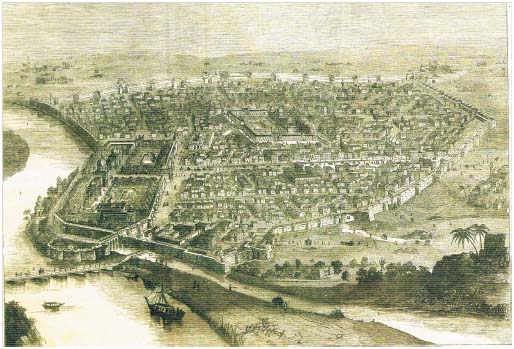

It won’t be a mistake to say the Yamuna is Delhi’s real town planner. One major river, its 18 tributaries, and some 800 big or small tanks and lakes dotted Delhi from one end to the other. Add to this layout of the city a few thousand wells and bavdhis.

This design ensured Delhi was never short of water, never had a famine, and was never ravaged by floods.

Among Delhi’s many names you will come across the name Indraprasth. Indra, the god of rain, wields the thunder. In our puranic accounts, another name of Indra is Purandhar, meaning the destroyer of cities. The bigger reason for that destruction, though, must have been the flaws in our town planning. In destroying cities, Indra’s main weapon must have been extraordinary rainfall.

In Delhi’s case, Indra did not have much luck. It is safe to assume that every time his heavy, rain-bearing clouds visited Delhi, their downpour was channeled in an organized and beautiful manner to tanks and lakess across the city. The water was not allowed to flood any localities.

After the monsoon, the water in the tanks seeped into the ground, keeping the water table high till next summer. To the blue of this water planning was added the green of vegetation. The Aravalli ridge was well forested, and there were gardens and orchards across Delhi. You will find the names of some of those gardens in the names of some of localities and Metro stations today.

Later, the English rulers decided to move their capital to Delhi. Before building New Delhi, Lutyens surveyed the land, mounted on an elephant. There is an account of a beautiful river flowing through where India International Centre and the Lodhi Gardens stand today. There was also a stone bridge to cross the river.

This river came from somewhere around Safdarjang’s Tomb, went through where Khan Market is today, and filled the moat of the Purana Qila before meeting the Yamuna. What were the pressures that made Delhi forget its rivers, erase them form the map, or turn them into sewers?

Those pressures are now backing the Yamuna’s riverfront development, along the lines of the Sabarmati. We tend to forget that these meandering rivers were not designed on a drafting board to flow in slide-rule-straights. Europe has tried to embank and channel several stretches of its rivers, but Europe does not have the world’s most powerful monsoon system. Will this work in India, where most of the annual rainfall occurs in a four-month season?

The wisdom of such schemes is debatable. It will definitely open hundreds of acres for real estate development. But it will expose us to another possibility: if it rains more than two to four inches in the upper catchment of the Yamuna, the river may jump its riverfront and inundate a bigger area than what becomes available for real estate development.

If that happens, it will be wrong to call it a natural disaster. Our town planners should consider such factors in their work. If they do, riverine cities like Delhi will not get abandoned very soon.

This article was originally written by Anupam Mishra and translated by Sopan Joshi. It has been reposted from the Journal of Landscape, No 35, April-June 2012.

Anupam Mishra is an eminent environmentalist, working in the area of water conservation, water management and traditional rainwater harvesting techniques all over the country. He is the recipient of the Indira Gandhi Paryavaran Puraskar award instituted by the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. He has authored many books that include Aaj Bhi Khare Hai Talaab and Rajasthan Ki Rajat Boondein.