"The men say that the well is perennial", I said. "Do you use it"? "No", replied the women. "It might be perennial, but the water is unclean. Our dals don't cook, and there are sometimes worms in the water".

"The men have decided that one standpost tap for 20 households is enough. Do you agree"? "No! Who will waste the entire day standing in a queue? We want one for every 5 households".

These women didn't disagree just to oppose the men. Their responses were very relevant and carefully-considered. And these were just two of those that were received from the women who participated in a village planning exercise in rural Jharkhand. Had I not been there, goading the male meeting participants into addressing them, the women would not have been consulted at all!

Business as usual: The exercise was about domestic water, and despite the established fact that this is a task that falls on the women, only the men were being conversed with by the team I was accompanying. The team did not mean to ignore the women that were present; they just did not see them.

I remonstrated with the team after the meeting. "You don't understand, Madam", I was told. "The women here refuse to come to meetings". I pulled out my camera and showed them the photos that I had taken over the few days I had been there. The team was sitting and talking intently to about 7-8 men, while around the group stood a dozen women. Silent, but waiting.

What was strange was that this was an excellent team. I was with them for a week and was astonished at their diligence in reaching far off villages to engage in a detailed planning exercise. I was there as a young local man, now a part of this team, got excited about a well that had a good supply of clean water. I watched him measure the well, talk about it, inspect the water. As a colleague remarked to me, this was probably the first time in his life that this young man considered a well to be something truly special, and this was only because of the team he was associated with.

The team members were doing a difficult job with a great deal of skill, perseverance and integrity. Their blindness to women’s' participation however, threatened to negate the other excellent work they were doing. With anything else, 50% achievement means a job half done.

But there is no such thing as partial participation; it is all or nothing.

Attempting change in the Himalayas: At the same time that the development workers in Jharkhand were facing my ire because of their gender blindness, another organisation in the Himalayas had learnt its lessons and was making a concerted effort to include everyone in their groundwater management programme. Compared to Jharkhand, the women of the Central Himalayas have a history of activism; one would not think that they would be diffident in planning their water resources but that was not the case.

"When women come to village meetings, they see their inlaws sitting there- maybe a father-in-law, maybe their husbands. It is quite impossible for them to speak in front of these relatives, let alone contradict them. However, it is also true that women know most about their water sources and their water needs", said Ganga Bisht, the programme head at CHIRAG. "We decided to make sure they alone controlled this management but we failed".

The team had first attempted to include women's voices by excluding those of the men. The programme called for villagers to get together into small groups that would study their spring, implement restoration measures, and come up with a system for equitable water use. For this, the CHIRAG team formed women-only water management groups (Jal Samitis). As they later learned, these did not work very well.

Excluding men is as counterproductive as excluding women. All the adults living in the vicinity of a spring turned out to have a role in its management. The team reassessed the situation and decided to include both men and women in the spring management committees. To shake up the traditional hierarchy, the positions of authority in the committees (President and Secretary) would be held by women.

Here, Ganga ran into a second obstacle- her team. Like the team in Jharkhand, the one in Uttarakhand was well-intentioned but clueless about how to begin. They did try, but the largely-male team was unable to strike a rapport with the women. Perhaps they were not entirely convinced either. Ganga now discussed this with her boss, Mukul Prasad, and they decided to bring in help. That's when Nandini Rao entered into the picture.

Ganga, Mukul, and Nandini chalked out a year-long programme of meetings and workshops with the CHIRAG staff and  spring committees. The idea behind including Nandini was to bring in all the weight of the opinion of an 'external expert' and to use the various tools that she was able to use to communicate awareness about inclusion. The strategy worked better than Mukul and Ganga had hoped. Partly through her tools but mostly through her outspoken intolerance for any discrimination, Nandini created a cadre of converts.

spring committees. The idea behind including Nandini was to bring in all the weight of the opinion of an 'external expert' and to use the various tools that she was able to use to communicate awareness about inclusion. The strategy worked better than Mukul and Ganga had hoped. Partly through her tools but mostly through her outspoken intolerance for any discrimination, Nandini created a cadre of converts.

The impact: Now, it is a pleasure for a grumpy feminist like me to participate in CHIRAG's spring committee meetings. The men and women are equally inspired, knowledgeable and articulate. And it is not just the Samiti members. The groundwater management team members exude the same confidence and camaraderie when addressing meetings. For them, people of the opposite gender are no longer a different species. Work becomes marvellously easy when you have a whole village on your team.

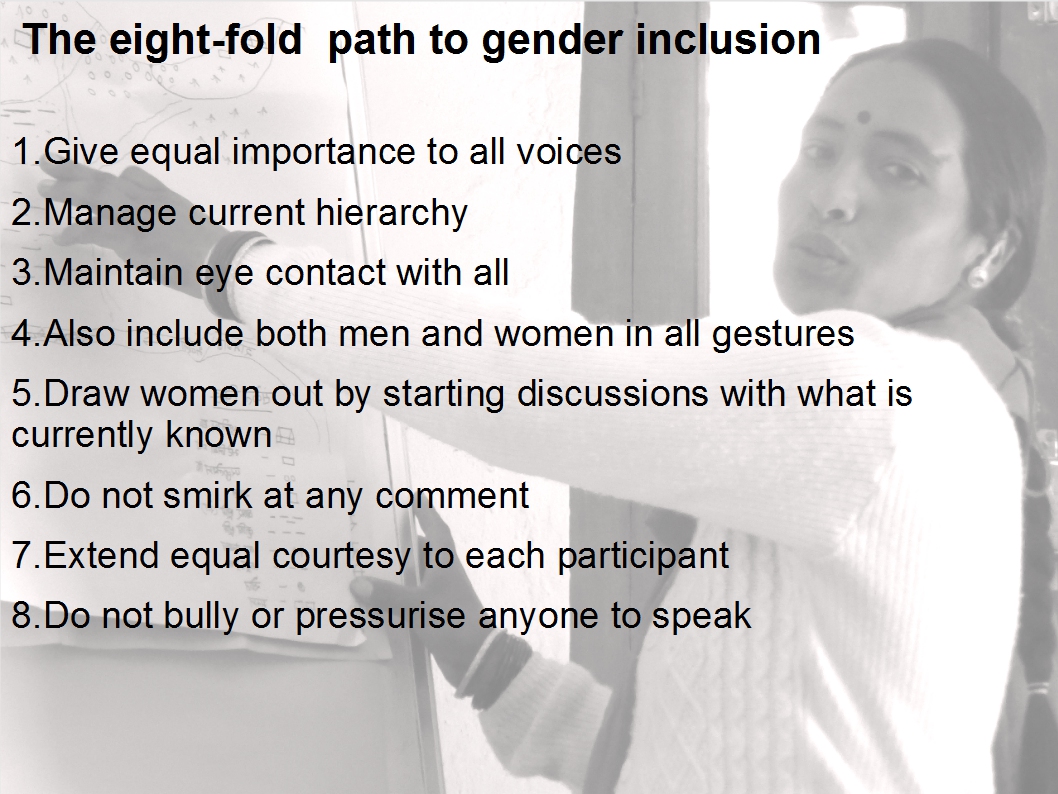

Gender inclusion Dos and Donts: Hoping to extend this circle of influence, I asked Ganga and Nandini for quick tips to ensure that both women and men take ownership of their resources and issues.

- Women are legitimate too! It is your responsibility as the development worker and the host of the meeting to give them importance. This encourages the community to do so as well.

- Convince the “people in power” (usually the men-folk) that it is important to listen to women’s voices. This is critical to ensure that the men in the community give space for the women to express themselves.

- Make eye contact with both men and women. In rural India, women and men customarily sit separately for all public functions. This perhaps symbolises the communication gap between the genders. But there is no point in wasting energy trying to change a symbol. Instead, accept the seating arrangement and foster communication yourself. Make it a point to look at both the men and the women throughout the discussion.

- On that note, body language is important. Make sure you do not exclude either the women or the men in your gestures, posture, or the way you face your audience.

- Start with what is known. There is knowledge within each person, but the means of communication are often stilted. It is your responsibility to figure out what the women know and initiate a conversation around these issues. Sooner or later, this will give them the confidence to respond to other issues too.

- Don't dismiss any comments. Most rural women do not have any practice at articulating their thoughts in public. But within those rambling sentences is a morsel of truth. Seek it out, acknowledge it, use it, praise it.

- Everyone expects respect. When women enter the meeting room, extend them the same courtesy you'd extend to the Pradhan. If they hesitate to express themselves, do not shame them. Make them feel welcome, and they will come for the next meeting and express themselves better.

- No one likes a bully. Forcing people to speak is counterproductive. Yes, participation is important but no one is going to perform for our gratification. Very often, a usually articulate woman may fall silent because her in-laws are in the crowd. Respect her desire to keep a low profile.