Indian activists have been campaigning for the last three years for a justiciable right to water and sanitation. According to the framework of this right, it provides a legal framework to hold states accountable, and provides principles to assist states in prioritising where resources should be dedicated. Providing this right will entitle everyone to safe water and sanitation services, and mandate that governments are obligated to ensure that everyone gains access to these services within a specified timeframe.

This issue was discussed at length during the recently concluded World Water Week. Léo Heller, Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation, United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights presented some basic principles and concepts of the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation. It is a powerful framework to orient how the provision of water and sanitation services are taking place and to also guide planning, and public policies. This article presents the points made during these discussions.

The human right to safe drinking water and sanitation is based on two major declarations. These are the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the resolution of the General Assembly in July 2010 that recognises the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation as an universal right. The key principles that are applied not only to the right to safe drinking water and sanitation, but to the entire set of human rights are listed below:

- Equality and non-discrimination: This means that all the segments of society --indigenous people, homeless people, prisoners, all those that are traditionally discriminated against--have the right to be provided adequate water and sanitation services. No one should be left behind.

- Participation and inclusion: It is necessary to have very transparent and efficient channels for participation. It is a duty of the government to open spaces for this participation.

- Accountability: Governments have an obligation to deliver information to people that might be users or non-users of their service.

- Sustainability: This means that it is necessary to have a progressive realisation of this right. When we face situations of retrogression, this can be considered a violation of the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation. This is very important because situations of retrogression are relatively common; for instance, in emergency situations, during droughts, during situations of displacement of population groups.

If we look at the issue of access to safe drinking water and sanitation through the lens of this principle, it will change the way we address it.

The human right to water can be defined roughly as the right that entitles everyone to available, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic uses. I would like to emphasise the affordability principle. In many cases the idea of cost recovery prevails and sometimes, this can be against the idea of providing water to those of low economic capacity.

Regarding the human right to sanitation, we have similar concepts adapted to the reality of sanitation access. These are availability, safety (mostly related to hygienic use), socially and culturally acceptable, accessible and affordable in all spheres of life, and providing privacy and dignity. Privacy and dignity are important concepts of the right to sanitation and has an strong gender dimension.

It is interesting to look at the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) through the lens of human rights to water and sanitation. The target of the MDGs was to halve the total population of people without access to water and sanitation in 15 years. The question is, 'Who is the half of the population who has not had access'?

These deprived people are around seven hundred million inhabitants worldwide, around 9% of the global population. This is not accurate since the statistics do not say anything about water quality or even quantity, but only talk in absolute terms about households that have access to water. Similarly, the statistics on sanitation say nothing about inequalities of access, or of where the wastewater is being discharged. We have around 2.4 billion people, or 22% of the global population without access to improved solutions to sanitation, 70% of whom are in rural areas. Around 1 billion people practice open defecation. This is one of the concerns of the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The target of the SDGs is to end open defecation in the next 15 years.

These deprived people are around seven hundred million inhabitants worldwide, around 9% of the global population. This is not accurate since the statistics do not say anything about water quality or even quantity, but only talk in absolute terms about households that have access to water. Similarly, the statistics on sanitation say nothing about inequalities of access, or of where the wastewater is being discharged. We have around 2.4 billion people, or 22% of the global population without access to improved solutions to sanitation, 70% of whom are in rural areas. Around 1 billion people practice open defecation. This is one of the concerns of the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The target of the SDGs is to end open defecation in the next 15 years.

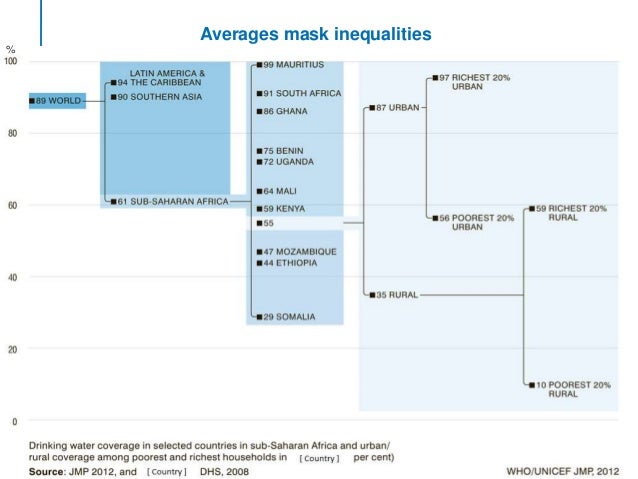

When we talk of the targets, we are talking about the outcome of the process. But when we consider who will have the access first, we are discussing the process itself. This discussion of the process is important because averages mask inequalities. When we say that 56% of the worlds population has piped water on the premises, we are masking that the difference between regions is very high. Differences are very real, they are important, and we need to address them. Looking at access to water and sanitation through the human rights lens forces us to disaggregate the data.

Leo Heller's talk underscores the discussions in India about the way target-driven sanitation programmes exacerbate inequalities between the rich and the poor. As he points out, a rights based approach may be the tool that is required to force us to consider universal access to safe water and sanitation.

If you are interested to know more about a justiciable right to water and sanitation in India, read the position paper of the Right to Sanitation campaign in India.