This couldn't have been more relevant to the conversation that we are having here. Michael Specter of the New Yorker wrote in his piece THE LAST DROP, on confronting the possibilities of a global catastrophe. I put his words as they are.

As countries become more industrialized, pollution and economic inequality increase—often dramatically—and so does the use and abuse of natural resources. Eventually, though, as the gross domestic product of a nation rises, technologies mature, efficiency improves, and so does the amount of attention paid to human welfare and the environment. (This general phenomenon is known as the Kuznets Curve, after the Nobel Prize-winning economist Simon Kuznets.) In 1965, Japan needed fifty million litres of water to produce a million dollars’ worth of goods. By 1989, the figure, after adjusting for inflation, had dropped to thirteen million litres. Such statistics suggest a fundamental change in how people live, and Gleick, among others, has argued that, in order to abandon what he calls the “hard path,” planners, economists, and public officials must begin to address water use in an entirely new way. “The hard path treats our water problems as a simple issue of getting more from the environment, of finding new ways to take water from rivers and lakes and aquifers and move it farther and farther and farther away, completely independent of any analysis of how we are moving that water or how we are using it,’’ Gleick said. “That is what the World Bank guys and traditional water engineers were trained to do. That is what we did in the twentieth century. It brought great benefits, but it has not solved all our water problems, and it is not going to.

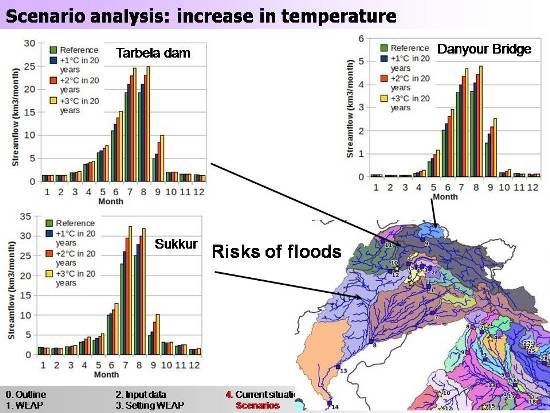

An entire new way could also include assessment and planning the available water resources with the aid of computer models and simulations. Scenario analysis can contribute greatly to understand the situation and what the possibilities could be, under altered climatic or natural conditions. This kind of a tool can help planners and water managers to a great extent, considering that most of the water managers that we have had, were trained on the "hard path" as Gleick puts it. Solving problems can be aided with modelling inputs like that from the work of researchers at Stockholm Environment Institute using Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) tool.

I have to say that this was one of the most interesting presentations that I had ever seen, which visualizes various scenarios of water flow and glacial melt using WEAP.

Devraj discusses his work in using WEAP in the Indus-Gangetic basin project and his findigs on :

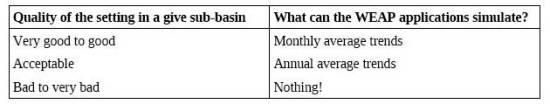

- Reliability of WEAP in Indus and Ganges basins.

- What can be achieved with WEAP in this basin.

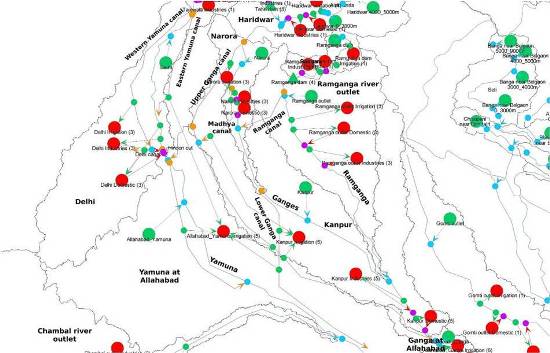

- Water uses in the ganges for different sub basins

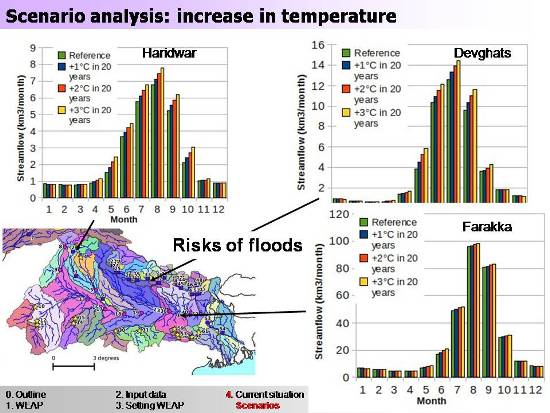

He performrs a scenario analysis which shows various possibilities and situations that may arise out of abrupt or unforeseen climatic changes. There are figures illustrating the consequences of reduced glacial flow and of an extreme situation when there isn’t any glacier left. The figures show what the volumes (of water) would be in the rivers under those conditions.

His objective is to develop an application of the Water Evaluation And Planning(WEAP) in the Indus and Ganges basin so as to:

- assess the water resources, in particular contribution from glaciers,

- model its utilisation / planning

- provide insight into some possible future scenarios.

Himanshu Thakkar remarks that the presentation was eye opening! "People have been asking what is the percentage of water flowing in the ganges… I found it here. This kind of data isn’t available with the Government of India too."

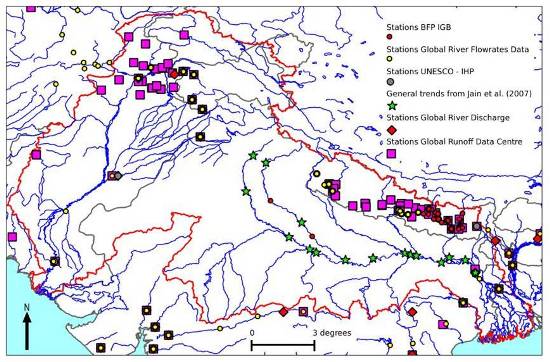

Observed streamflows:International databases; IWMI: Upper Kosi (Nepalese part) and Upper Ganges; some time series in the Indus extracted from the spreadsheet of Eastham et al. (2008); average annual trends from Jain et al. (2007) in the Ganges.

Generation of sub-basins with respect to: available observed time series of streamflows, large reservoirs or barrages, major river outlets (where some average annual flows were available).

Analysis current situation: impacts of canals

Gabgetic Basin; Considered 3 scenarios for 20 years: +1°C after 20-years, i.e., a rate of +0.05°C/year, +2°C after 20-years, i.e., a rate of +0.10°C/year, +3°C after 20-years, i.e., a rate of +0.15°C/year. Compared to the reference scenario = period 1982 to 2002

Indus Basin

Devraj shares many more scenarios for the Indus-Gangetic basin. Download his presentation here