As India continues to unravel the actual scale of economic impacts in a world infested by the dangerous Covid-19 virus, lingering images of daily wage labourers and migrant workers attempting a near impossible walk home have been etched in public consciousness. Lives and livelihoods of these labourers have been shattered and their long walks home have been met with hostility, forced quarantines, insensitive and often unscientific procedures in the name of sterilization, suspicion from their own people, and political games on their travel fares to return home. Locked down in lands far away from their safe spaces, and dealing with loss of livelihoods and lack of social security has been an unprecedented experience for large populations.

With migrant workers from across the country gradually returning to their home states starting April 29, there is expected to be a huge reverse migration across the poorer states. In the months to come, finding opportunities for this large population to earn a living in the new post-Covid context with physical distancing norms in place, is a challenge that needs to be addressed on high priority.

Bracing for the current situation and identifying avenues to cater to the increased job demand will be critical to ensure that the workers’ lives aren’t destroyed in the midst of the Covid crisis.

Among the various government schemes with the objective of citizens welfare and poverty alleviation, is the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). The scheme has shown tremendous potential to lift people out of poverty over the years, despite its inherent shortcomings and various attempts at weakening its core principles.

Can the pandemic be an opportunity to initiate modifications to the MGNREGS and can this be done with an eye not just towards the immediate crisis, but as a means to build a robust, future-looking, welfare scheme that addresses employment and livelihood challenges faced by the most vulnerable sections in a post-Covid world? We explore the answers to these two questions in this article.

MGNREGS - The past and the present

In a modern welfare state, provision of employment is a primary mandate for the government. In the case of MGNREGS, the government is the employment provider and also a guarantor of employment rights. The MGNREGA, enacted in 2005, promises 100 days of wage employment in a financial year to every rural household whose adult members are willing to engage in unskilled manual work. Initially, the Act was intended to cover 200 backward districts in India, but subsequently its scope was extended to all parts of rural India.

Participants enter the MGNREGS through self-selection. Several studies indicate that the programme has improved wage rates locally, increased bargaining power of labourers and improved participation of women, Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in the workforce. Not only have the marginalised sections been participating more in the programme, but they have derived more benefits as well. Several studies have investigated the impact of MGNREGA on the welfare of the poor. Studies also indicate a strong correlation between MGNREGS and food/nutritional security of the households.

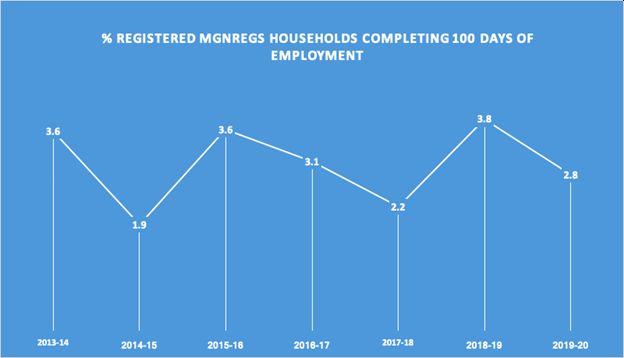

Of concern is the fact that despite the promise of 100 days of employment, not even 5% households have actually achieved 100 days of employment over the last 7 years (refer Fig. 1). The average number of days of employment provided under MGNREGS peaked at 54 days in FY 2009-10 and has been hovering below the 50 days mark for the most part.

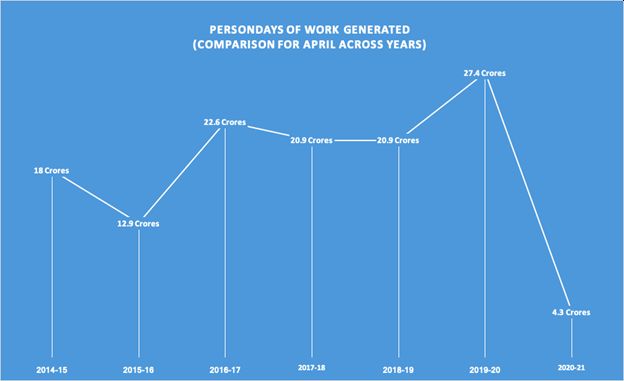

During fiscal year 2019-20, top categories of MGNREGS works were (as per expenditure estimates) Work on Individual Land, Water Conservation and Harvesting, Drought Proofing, and Rural Sanitation. Significantly, the person days of work generated in April 2020, saw a reduction of 84% compared to April 2019, lower than any of the last 7 years (refer Fig.2). Only 34 lakh households got work in April 2020 compared to 1.7 crore in 2019. This clearly illustrates the impact that the Covid-19 situation has had.

Recently the Finance Minister announced a 1.7 lakh crores relief package, which included an increase of Rs. 20 (Rs. 182 to Rs. 202) in MGNREGS wages. Considering that the MGNREGS wages were supposed to be linked to the Consumer Price Index (Rural), instead of the currently used Consumer Price Index (Agricultural Labour), Covid-19 situation did not actually influence the wage increase after all. Most states pay better daily wages than Rs. 202 anyway with agricultural minimum wages exceeding MGNREGS wages in 33 states and Union Territories, Nagaland being the only exception. The number is also substantially lower than Anoop Sathpathy committee’s recommendation, a national minimum wage of Rs. 375.

While being pivotal to ensuring rural livelihood security, MGNREGS is entrenched in multiple problems such as inadequate funding and poor daily wage rates; lack of political commitment, weak local governance structures, delays in payments, faulty monitoring systems, missing social audits and incomplete physical works etc.

However, despite these inadequacies and sub-optimalities, MGNREGS holds the potential to improve rural lives and livelihoods, in the short and long term. But a radical transformation of the scheme will be necessary.

Transforming MGNREGS (MGNREGS 2.0)

Most of the activities under MGNREGS rely on group labour work, and with the physical distancing guidelines becoming the norm - possibly for months - the focus of the scheme should be on individual labour in the short term. Here we lay out some suggestions for what could be done for the rest of the year and in the long term.

A. Short Term (May to December 2020)

1. Expand the scope of activities:

- For landholders - It will be prudent to bring all individual land/farm development activities under MGNREGS (including harvesting). Construction of individual houses under the PMAY (Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna) should also be subsumed under MGNREGS. Farm level water conservation measures like farm ponds, percolation tanks, recharge pits should be promoted under MGNREGS. Kitchen gardens, livestock development and animal husbandry should be promoted too, which will help to ensure food and/or nutritional security of the households.

- For the landless - MGNREGS should pay for the farm labour carried out by landless labourers. Post the harvest, the landless labourers can help to transport the crop to the mandis/APMCs. They can also help with milk procurement, cooking and supplying meals to individual households, renovation of PHC/Sub Centres and construction of health centres in the villages. The landless labourers can also contribute to manufacturing masks and sanitisers. All these activities can be brought under MGNREGS. Accessing MGNREGS payments during the lockdown will be a difficult proposition with banks being understaffed and ATM’s often being kilometres away from villages. Hence, some of the landless labourers could also double up as the banking correspondents.

2. Pay minimum wages in advance: With the lockdown in place, and no immediate sources of income in sight, wages should be paid in advance (for 6 months) to all active job card holders and other job card holders demanding work. In accordance with announcements made by the Finance Minister, all participants in MGNREGS should be paid Rs. 202/day or more. This will fit well with the prime minister’s notice to employers to pay their staff during the lockdown. In this case, the government is the employer.

3. Introduce special waivers: All work done over the next 6 months under MGNREGS should be over and above the original 100 days guaranteed under the scheme.

4. Allow temporary tenure: Large scale reverse migration due to the countrywide lockdowns, will leave many citizens in rural areas jobless. Many of them may not be registered under MGNREGS or might have inactive job cards. Using any existing government document for verification (ration card, Aadhar card, voter identification card etc.), these citizens should be allowed to work under MGNREGS, at least for next 6 months, during which the process of job card registration should be completed.

B. Long Term (2021 onwards)

1. Introduce a country wide open well construction and revival campaign: MGNREGS has an inherent emphasis on water security. Among other things, the Covid-19 situation has taught us the importance of water security and frequent handwashing. Building on this understanding, the Government of India should introduce a countrywide open well campaign similar to Mazhapolima in Kerala and the “Million Wells Campaign” in Bengaluru. This campaign will contribute to household level water security and climate resilient infrastructure. It will also help us to prepare for the next pandemic and/or natural calamity.

2. Plan for an urban employment guarantee scheme: Urban poor, who continue to live in cities, will find it difficult to deal with the crisis. To help them earn their livelihoods in the long term, an urban employment guarantee scheme (similar to MGNREGS) should be considered as soon as possible. In case the private sector fails to provide a predetermined number of days of employment, the public sector should employ the urban poor to overcome the shortfall. Public works like waste management, drainage and roadside cleaning can be brought under the new scheme. In a post-Covid-19 world; hospitals, health care centres and quarantine facilities will also need semi-skilled and skilled employees; with some training and/or skill building the urban poor could fill in the gap.

While putting MGNREGS 2.0 into action, some structural changes will be necessary to facilitate the implementation. Instead of focusing on convergence at this moment, it will be useful to simplify scheme architecture and streamline financial flows. MGNREGS should be used as a flagship scheme to improve rural and urban livelihoods. Any infrastructure/asset creation in rural and urban areas should be funded by MGNREGS (including building piped water schemes for households under Jal Jeevan Mission)

Welfare as a pivot for the future

Welfare schemes like MGNREGS have contributed significantly in providing relief to the poorest sections of society. It has immense scope to be an instrument of immediate and sustained relief for the most severely impacted communities in the current Covid-19 crisis. To win our battle against this deadly virus as a nation, it is imperative that we safeguard our most marginalised citizens. MGNREGS has the potential to not just help in tiding over the COVID-19 crisis, but also to build systemic resilience to prepare for any future emergencies. Living up to Article 38 of the Indian Constitution - referred to as its keystone and fundamental to its very spirit as part of the Directive Principles of State Policy - is the bare minimum that we as a nation can hold ourselves accountable to in these times of crisis. Time is at a premium, and we need to act fast.

Karthik Seshan is a development consultant. He used to lead the Water Quality portfolio at Arghyam, and has worked extensively on issues of water (in)security across the country, covering aspects of practice, research and policy.

Ayan Biswas leads Akvo’s (www.akvo.org) operations in East and Southern Africa. He has worked on development issues cutting across science, policy, practice and people in India/South Asia for more than 15 years.

Views expressed in the article are in the authors’ personal capacity and they acknowledge the collective intelligence of their friends, colleagues and peers for their thoughts and contributions.