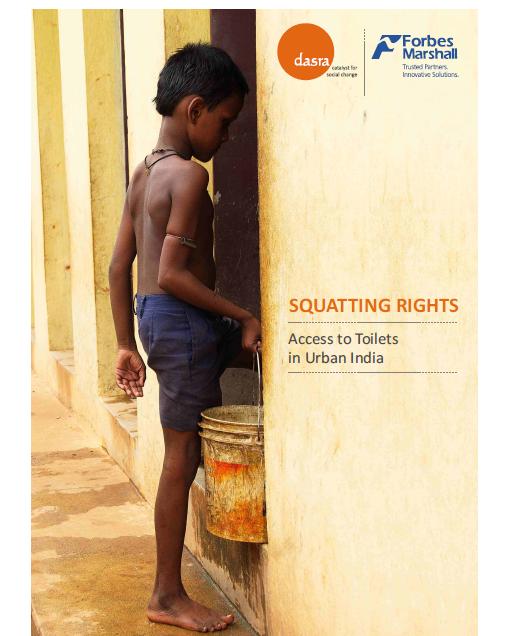

Dasra, a strategic philanthropy foundation in collaboration with Omidyar Network and Forbes Marshall has recently come up with a report “Squatting Rights” that highlights that recent policy developments focusing on urban sanitation coupled with strategic philanthropic funding, can go a long way in providing urban poor with access to improved sanitation and ensuring healthy, prosperous cities.

Dasra, a strategic philanthropy foundation in collaboration with Omidyar Network and Forbes Marshall has recently come up with a report “Squatting Rights” that highlights that recent policy developments focusing on urban sanitation coupled with strategic philanthropic funding, can go a long way in providing urban poor with access to improved sanitation and ensuring healthy, prosperous cities.

Dr. Bindeshwar Pathak in the foreword to the report notes that “the challenges that the urban sanitation sector faces mainly relate to the low priority accorded to it – whether by the bureaucracy, the municipalities or the households themselves.”

Even today, millions of Indians are subjected to grave ill health, increasing threats to safety, lower spending on education and nutrition, reduced productivity and lower income earning potential resulting into a deepening cycle of poverty – all for want of a basic sanitation facility.

The report says that sanitation, particularly for urban areas, remained a neglected subject in India for a long time, becoming an important policy concern only around 2008. Policy created since then provides a role for all stakeholders, including non profits, involved in providing sanitation to India’s urban residents.

The report begins with the message that lack of sanitation is not a symptom of poverty but a major contributing factor. It goes on to say that “adequate sanitation is a basic human right. Its lack is related to, and exacerbates, other burdens of inequity experienced by marginalized urban households, deepening the cycle of poverty. The lack of sanitation increases living costs, decreases spending on education and nutrition, lowers income earning potential, and threatens safety and welfare. This is especially true for urban India.”

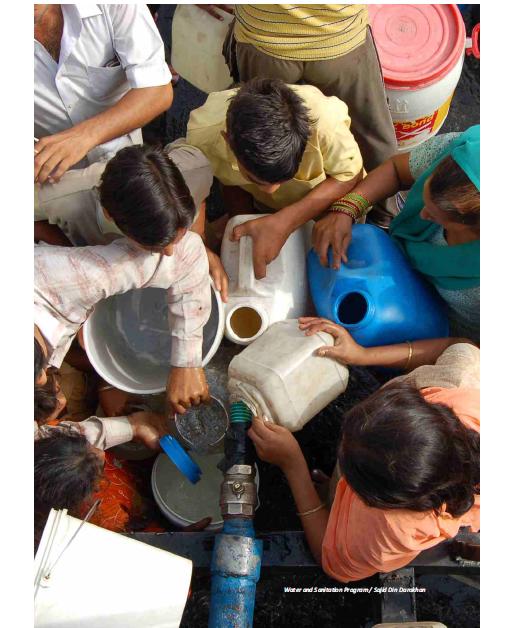

The report says that India’s cities are not only increasing in number, they are also expanding, and so are the slums  within them. Sanitation in urban slums is a complex and pressing issue. Existing unhygienic standards, crowded conditions and poor sanitation contribute to frequent and rapid outbreaks of disease. Lack of access to healthcare facilities compounds health problems. This negatively impacts gender parity, education and livelihoods, making slum populations even more vulnerable.

within them. Sanitation in urban slums is a complex and pressing issue. Existing unhygienic standards, crowded conditions and poor sanitation contribute to frequent and rapid outbreaks of disease. Lack of access to healthcare facilities compounds health problems. This negatively impacts gender parity, education and livelihoods, making slum populations even more vulnerable.

The poor bear the worst consequences of inadequate sanitation in the form of ailing children, uneducated girls and unproductive people, making these populations even more vulnerable and costing India 6.4 per cent of its GDP.

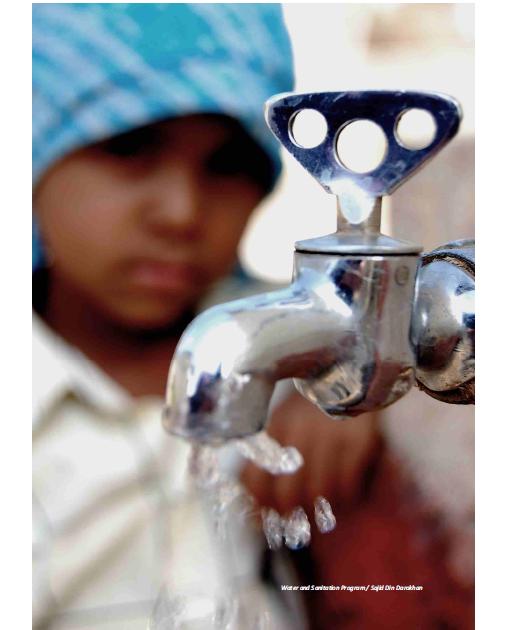

On the point of sanitation and women the report suggests that for women the daily struggle begins well before dawn. Without water supplies and toilets within their homes, and unable to openly defecate during the day due to lack of privacy and for fear of harassment, they wait for nightfall and to find a secluded spot to defecate, a practice which has serious side effects.

Waiting so long to relieve themselves increases chances of contracting urinary tract infections, chronic constipation, and psychological stress, the report argues. That apart, it creates irreparable complications during pregnancy and postnatal recovery. Also, travelling long distances to access public facilities makes them potentially vulnerable to physical and sexual assault. A United Nations survey suggests that it is not uncommon for girls and women in such conditions to be harassed, physically assaulted and raped and that in Delhi slums, up to 70 per cent of girls experience humiliation every day in terms of verbal harassment and half of them have been victims of grave physical assaults.”

The report notes that “even nations with lower per capita income such as Bangladesh and Pakistan are scoring far better than India on various sanitation indicators serves as a wakeup call.”

The report in the section “Sanitation - A blue chip investment” highlights that sanitation brings the single greatest return on investment of any development intervention– for every $1 spent on sanitation at least $9 is saved in health, education and economic development. Despite this well established fact, in India this sector has remained neglected for most of its post-Independence history.

The report in the section “Sanitation - A blue chip investment” highlights that sanitation brings the single greatest return on investment of any development intervention– for every $1 spent on sanitation at least $9 is saved in health, education and economic development. Despite this well established fact, in India this sector has remained neglected for most of its post-Independence history.

Dasra in the report recommends five cornerstones that are crucial in providing universal urban sanitation in India: 1. Developing a gendered approach 2. Improving hygiene 3. Fostering champions within Government 4. Nurturing community ownership and 5. Customizing solutions and creating standards.

Sanitation projects designed with full participation from women are five to seven times more successful than those that focus only on men. It is vital to acknowledge the distinct role of men and women and involve them both as important actors, stakeholders and change agents for improved sanitation.

Diarrhea alone kills one child every minute in India. The most affordable, accessible and effective way to prevent this is to promote hygiene in marginalized communities. It is essential to educate communities about the life saving potential of simple hygiene and its key role in helping populations realize the full return on infrastructure investments.

Government’s involvement in the sanitation sector is one of the most important factors behind sustainable and large scale sanitation outcomes not only in India but also other countries such as the Dasra recognizes that in India, urban sanitation cannot be provided by any one stakeholder. While the size of investment underscores the critical role of the Government of India, equally important is the role of the communities that will be ultimately responsible for making sanitation a sustained reality.

Along with the government and communities, non profits play a pivotal role in the sanitation framework. Non profits are best placed to demonstrate innovative, impactful models due to their proximity to communities and have the potential to scale those initiatives by facilitating partnerships among various key stakeholders, the report states.

Dasra recommends that philanthropists fund non profits that are training stakeholders, enabling behavior change for hygiene education and influencing government as these are the three most scalable and high – impact interventions undertaken currently to provide access to sanitation in urban India.