I could just about see a small makeshift shelter with a yellow canopy. As I made my way through the small stream and climbed uphill, I saw a JCB machine trying to clear a path. Further up the road, female voices speaking the local dialect started to emerge. A small hearth surrounded by utensils and jars of tea, sugar and lentils greeted me at the entrance.

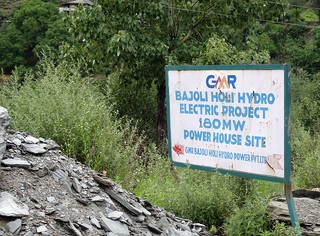

Until last month, this was the dharna (strike) site for around 60 Gaddi tribal women of Holi village protesting the 180 MW Holi-Bajoli hydropower GMR project. Around 70 km from the district headquarters of Chamba in Himachal Pradesh, this is also the site for the edit tunnel and powerhouse of the project. The women had been sitting here in shifts for over three months lest the construction and road work begin. As I write this, news came in that the dharna has been called off but not because the problem was resolved. Bureaucratic and political intimidation had silenced the villagers again even though the battle continued in the courts.

It had never been easy for these women. As many as 31 of them were arrested on March 25 under non-bailable charges. They came back to the site after their release and continued the protest. The reason was simple: their houses, fields and forests will be destroyed if the hydel project takes off.

Villagers want the project to be shifted to the right bank of the Ravi river, which was the original proposed site of the powerhouse. “We gave the no-objection certificates to the company believing that the project will come up on the right bank which has no habitation, no orchards and no fields. Nobody knows how the site was changed from left to right bank. We also want development of the area but not at this cost,” said Bujhli Devi, who has been accused in four cases ranging from deterring a public servant from doing his duty to spreading enmity between different groups of people.

The project spans five panchayats but it is at Holi that the voices grow louder with mainly women taking the lead. The project will not only impact their houses but also the local economy which thrives on apple orchards, kidney beans and walnuts. “We women earn around Rs 1 lakh annually through sale of apple, walnuts and other forest produce. The field crops are another major source of sustainable income which will be destroyed if the powerhouse is constructed here,” said Pinki Devi, another woman leader who has been accused in seven cases.

Though the company claims it will take all precautions to avoid damage to the houses and fields, villagers are not believing them. They have already seen the impact of tunnels dug for the Chamera 3 hydel project at Dharwala village, around 45 km from here. The leakage from the tunnel has caused extensive landslides in the area damaging houses, shops and farms thus pushing the residents out.

Why is right wrong?

The state government allotted this project to GMR in 2007 through international competitive bidding with project proposal on the right bank. Assessments done by planning and design engineers of the Himachal Pradesh State Electricity Board Limited (HPSEBL) in consultation with geologists from Geological Survey of India (GSI) also preferred the right bank recommending a pit-type powerhouse. However, by the end of 2008, the company decided to shift it to the left bank. The reason that GMR preferrs the project to be on the left bank rather than on the right is the comparative ease which comes with switching sides. Since the left bank is already populated, it already has basic infrastructure like access roads. It also has flatter slopes when compared to the steep cliffs and rugged terrain of the right bank.

As villagers protested such a change in location, Chamba’s Deputy Commissioner sought HPSEBL’s opinion. In his reply on February 22, 2011, chief engineer of HPSEBL disapproved of the justifications given by GMR for shifting of the project. He said that the left bank had subsurface water sources, lakes and ponds which may dry up due to construction activity. The left bank was also found to be geologically more disturbed due to heavy landslides. GSI mentioned that ingress of water is expected to be higher on the left bank due to better forest cover and more streams. However, MoEF and Special Secretary (Power) of the Himachal Pradesh government approved the shifting.

In February, 2012 challenging the environment clearance and first stage forest clearance to the hydel project, Mangni Ram of Gadoh village approached the Himachal Pradesh High Court. The petition quoted the opinion of HPSEBL to strengthen its case. With its letter reaching the court, HPSEBL decided to have first-hand appraisal of the project which further strengthened its position. In his report (see attachment), Director (Civil) said the right bank is the more natural choice as “the green cover and habitation is insignificant and hence damage to ecology will be negligible". The proposal of the company is guided by commercial advantages of the left bank option, namely, short lead time to commencement of construction as well as savings in infrastructure.

While the discomfort to the company will be for a short period of 5-6 years, losses to the public and the environment aren't quantifiable. During the hearing, the court refused to consider this opinion noting that the Central Electricity Authority is the only competent authority and it has already given its approval for shifting the project. Mangni Ram has now appealed against the judgement in the Supreme Court. He contends that only HPSEBL has conducted a detailed analysis of the site and hence its opinion should be considered.

Not everybody opposing it

The first public hearing held on April 19, 2010, by GMR witnessed strong opposition from all the five affected gram sabhas. The Deputy Commissioner announced that the next public hearing will be called only when the company obtains no-objection certificates (NOC) from all of them but by the time the next public hearing was held on October 30, 2010, most of those present approved the project with conditions that the company takes adequate care regarding the possible damages, adequate compensation and ensures guaranteed employment to the locals in the project. The Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) of the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests also accepted the company’s case for the project on left bank.

The first public hearing held on April 19, 2010, by GMR witnessed strong opposition from all the five affected gram sabhas. The Deputy Commissioner announced that the next public hearing will be called only when the company obtains no-objection certificates (NOC) from all of them but by the time the next public hearing was held on October 30, 2010, most of those present approved the project with conditions that the company takes adequate care regarding the possible damages, adequate compensation and ensures guaranteed employment to the locals in the project. The Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) of the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests also accepted the company’s case for the project on left bank.

Though all five gram panchayats gave their consent to the project, two of them (Holi and Nayagraon) later withdrew their support citing the diversion of large forest land and possible loss to livelihood.

The issue of forest rights

The issue of forest rights in Himachal is a contentious one. The Forest Rights Act 2006 (FRA) gives ample privileges to those dependent on forests but Himachal Pradesh sought exemption from it claiming that all rights and concessions on the forest land were settled during the British rule and hence no FRA compliance issues exist. The Ministry of Environment and Forests also accepted the state government’s request to consider a certificate issued by the District Collector/ Deputy Commissioner as enough to meet procedural requirements of the Act and hence diversion of forest land for the project was approved.

The Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs and Panchayati Raj, however, objected to both these exemptions asking the state government to implement the law in a time-bound manner as the rights of forest dwellers may not have been recorded properly in traditional settlements and fresh rights may have originated. It also asked the MoEF to withdraw its consent to consider the District Collector’s certificate as enough for implementation of FRA. The MoEF, however, went ahead with the forest clearance based on the DC’s certificate thus not paying heed to the communication by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

The residents of Holi and Nayagraon, meanwhile, are adamant that their rights should be protected. “We get our fodder, fruits and fuelwood from these forests, how can the Deputy Commissioner say there are no forest rights to be settled in these areas?,” asks Bujhli Devi.

The answer is tangled in the web of bureaucratic and legal procedures.

As I took leave of the women protesters that day, they asked if the issue will be settled in their favour. I launched into a big talk about how it’s important to keep making efforts without worrying about the results. One of them said, “Efforts can only continue if we get some support once in a while. With increasing pressure from the police and political interference, we can only come so far”.