It was 1995. A 34 year old doctor working in the Regional Medical Research Centre for Tribals, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Jabalpur received an appeal for help from the District Collector of Mandla, Madhya Pradesh. A distressing number of young people in the two villages of Tilaipani and Hirapur were suffering from a painful and disfiguring ailment. The villagers believed it was black magic; the Chief Medical Officer was unable to provide a better diagnosis.

The young doctor was Tapas Chakma and his work over the next few months would define not only his career, but also public health care in Madhya Pradesh.

Initial investigations and diagnosis

Dr. Chakma and a small team camped at the villages for a few days. There, they discovered that nearly one-third of the residents of Tilaipani, and about 10% of the population of Hirapur had bowed legs and knees that nearly touched. This deformity, called Genu Valgam had been noted in fluoride-affected districts of Andhra Pradesh in 1973, and the fluoride contamination was attributed to upheavals in the soil strata due to construction of a dam. Central India however was considered to have low danger of fluoride contamination.

The team from ICMR conducted a battery of investigations including physical examination, radiological and biochemical tests, and dietary surveys. These led them to suspect fluorosis, a diagnosis that was confirmed when abnormally high levels of fluoride were found in the deep tubewells used by the villagers for drinking water.

The results

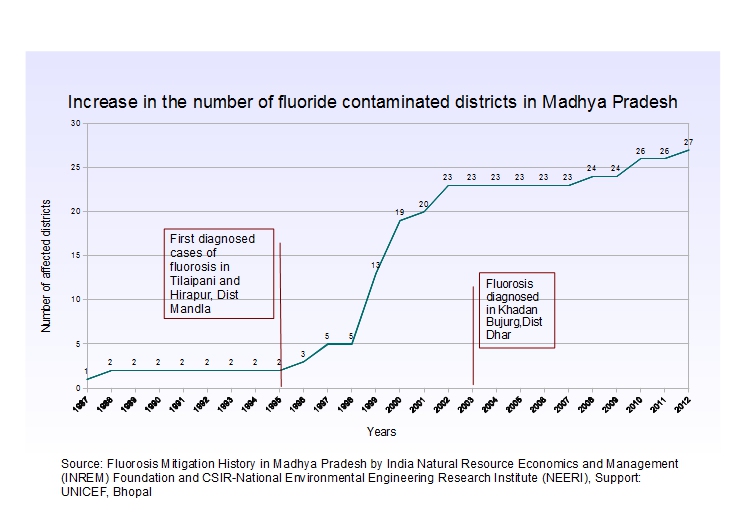

In a conversation with India Water Portal, Dr. Chakma recollected, “We recommended that all handpumps within a 50 km radius should be checked; 550 were found to be contaminated. The PHED acknowledged that they did not know of fluorosis. Very little was known at that time”. Dr. Chakma wrote to the MP government recommending that testing for fluoride content be made mandatory for all handpumps and this was accepted by 1996. However, the lessons of this experience had not been learnt by the public health system of the state as was demonstrated by the events of 2003.

History repeats itself

The place was a small tribal village called Khadan Bujurg in Tirla Block of Dhar, Madhya Pradesh. Three children in one family were exhibiting symptoms unfamiliar to the Primary Health Centre in the area. Their teeth were stained and they were beginning to show bone deformities. These previously healthy children were now stumbling as they walked and also had curved limbs. Once again, the villagers thought black magic had been exercised on the children while the many doctors they turned to diagnosed it as Polio.

When polio proved to be the wrong diagnosis, the report of these children came to the Block Development Office. UNICEF and PHED came together and exchanged notes on this phenomenon, and finally the children's strange ailment was identified as fluorosis. A team from the state research cell confirmed the diagnosis after having camped for several days in the first village.

Once aware that the disease was water-related, PHED sprang into action. They tested all the water sources in the area and began shutting down contaminated handpumps, which seemed like the most logical move given the context. However, PHED failed in one respect. When they started shutting down the handpumps, they did not give out any reasons. Naturally enough, they faced stiff opposition from the villagers and in some cases, PHED officials got beaten up and their vehicles got gheraoed.

UNICEF took on some of the responsibility of informing the people about what was going on, and they began working in 90 villages, 30 each in Nalcha, Tirla and Umarbond blocks. This was mainly to raise awareness about the significance of the red/yellow/blue markings which the people did not understand.

Soon, the organisations involved moved beyond merely talking about the importance of the marked handpumps. Dr. Samuel Godfrey (UNICEF) first put together a water safety plan, an effort that PHED also coordinated. NEERI analysed the food for fluoride content. Dr.Chakma and Dr A K Susheela conducted workshops to raise awareness about fluorosis The water safety plan was discussed and they came to wise water management, and from discussion to implementation.

NGOs and institutions got involved in awareness raising as a pilot before moving on to the villages. Vasudha Vikas Sansthan, one of the organisations that began working on fluoride contamination in the area, continues to work in this field today. Gayatri Parihar of Vasudha recollected, "Tribal hostels were identified in 3 blocks to provide options to contaminated water. Rainwater harvesting, grey water recycling, and improved nutrition were all implemented. This effort sadly petered out due to a lack of funds for operation and maintenance".

Sunderrajan Krishnan of INREM Foundation in a paper on fluorosis in Madhya Pradesh (2013) developed by NEERI with the support of UNICEF proposed integrated treatment of fluorosis that included providing safe drinking water and supplementing nutrition. This approach is strongly supported by Dr. Chakma, who pointed out that the provision of safe drinking water alone does nothing to combat the ingestion of fluoride contaminated food since in many places, people continue to use borewell water to irrigate their crops, which leads to high fluoride content in the produce. Adequate nutrition is a must to prevent the development of fluorosis in fluoride contaminated areas.

The situation today

Since the 1990s, the people of Madhya Pradesh have learnt important lessons. They now know of fluoride contamination and its reasons. This is not only due to extensive outreach by NGOs, but also due to a comprehensive outreach and mass communication programme by the government. There is an awareness of the types of interventions that have the greatest chance of success. Mishra, the Superintending Engineeer of Dhar confirmed that cooperation among the government departments is on the rise. He said, "PHED and the Panchayats work together to support measures to combat fluoride contamination. NRHM also now considers fluoride through the 'National Programme for Prevention and Control of Fluorosis (NPPCF)' in its Integreated Disease Surveillance Programme and has a separate budget for it, with fund sharing between the Centre and State in the proportion of 75:25". This means that regular training of health staff is carried out.

Despite these advances, there are still young children in the state today who suffer from fluorosis. To some extent, this is because of a lack of awareness among people living in rural areas. Ultimately however, this is a disease of poverty. People in the affected villages often suffer from chronic malnutrition which makes their bodies vulnerable to fluorosis. Organisations have identified several easily available traditional foods that can alleivate these deficiencies but the poor of India are also deficient in their access to knowledge.

Madhya Pradesh, unfortunately, has a long way to go before its children do not have to suffer from an 'avoidable' disease.