Raj Kumar, 32, a daily wager employed at a factory in Delhi had barely a thousand rupees in his wallet when he readied to rush back to his village in Halia block of Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh. On a normal April afternoon, he took the highway that leads to his district hearing about the 21-day lockdown. It took him over a week, as he walked down all the way to his village fearing starvation amid the Covid-19 crisis. Kumar trudged hundreds of kilometres along deserted highways by foot along with a few of his acquaintances. On the way, he was held and isolated by authorities at three different places at Ghaziabad, Kanpur and Prayagraj for a total of four days.

Thousands of migrant workers from Uttar Pradesh found themselves stranded in the wake of the countrywide lockdown enforced in India from March 25, 2020 as a precautionary measure to contain the outbreak of Covid-19. With the big cities getting shuttered due to the coronavirus, migrant workers set out for their homes in a desperate attempt to escape the unforeseen consequences of a prolonged lockdown. But with no savings and earnings to buy food, getting home was the only way migrants like Raj Kumar could survive. With rail and bus services shut down, Kumar was left with no option but to walk back to his village.

Images of migrant workers scurrying around in search of buses, trains and other modes of transport in various metropolitan cities and highways might go down in history as the most haunting pictures related to the outbreak of the pandemic in India. While some of them managed to return home, many remained stuck on the way surviving on supplies of food, water and basic amenities organised by local authorities and groups of supportive people on the way.

A rapid study of a sample of 60 migrant workers who managed to return home was anchored by Arthik Anusandhan Kendra, Allahabad and Praxis – Institute for Participatory Practices, New Delhi. The idea was to learn about the hardships faced by migrant workers during their homebound journey from various places in India, in the wake of the countrywide lockdown.

The study attempted to reach out to migrant workers while observing the requirement of physical distancing. The interviews were mostly conducted either telephonically or using remote instruments such as Google Forms.

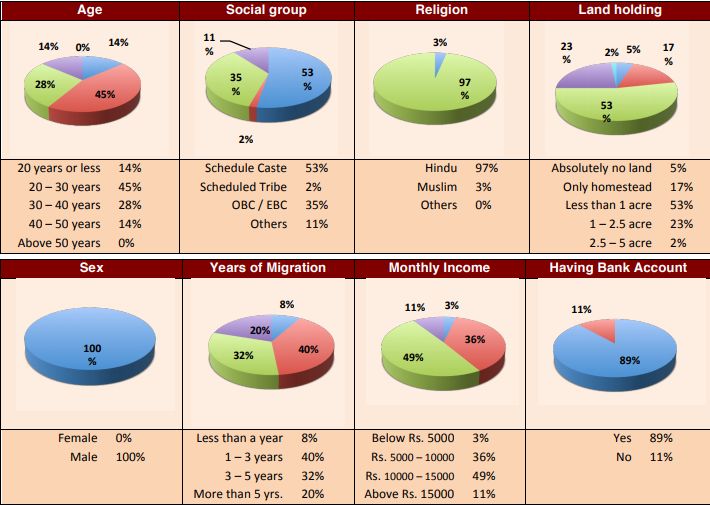

Majority of the workers belonged to the age group of 20 to 30 years (45%), hailed from Scheduled Castes (53%) and owned less than one acre of land (75%). 17% of the interviewees were in possession of only homestead land, while 5% were absolutely landless. 97% of the interviewees were Hindus.

Among the migrant workers interviewed, 25% returned from various worksites in Delhi. In addition, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Haryana emerged as popular destinations, with nearly 13%, 12% and 5% workers returning from worksites located in these states respectively. Rest of the workers (45%) returned from a wide range of worksites spread across multiple states. Commonest places visited by migrant workers include Delhi, Mumbai, Gurgaon, Surat, Indore, Kolhapur and Raipur.

Key findings of the study

- Main types of work: Work in factories (67%); daily wage labour (8%); taxi driving (7%); work as security guard (5%); agricultural labour (3%); work in hotels (3%); miscellaneous other domains (7%)

- Monthly income range: Rs. 10,000 – 15,000 (49%); Rs. 5,000 – 10,000 (36%); Rs. 15,000 – 25,000 (11%); Less than Rs. 5,000 (3%)

Reasons of returning home: Fear of coronavirus (43%); loss of livelihood (17%); fear of starvation (15%); retrenchment (12%); lack of shelter (7%); concerned about safety of family members (6%)

- Average money in hand, when decided to leave for home: Rs. 2,422. About 67% workers had Rs. 2,000 or less when they decided to return home.

- Proportion of workers who had to borrow money for returning: 17%; average amount borrowed: Rs. 1,150

Average expenditure in returning to village: Rs. 1,252 (ranged up to Rs. 5,000) - including expenses on food (37%), travel (59%), medicines (3%) and shelter (2%).

- Mode of return*: Bus (49%), walk (33%), train (13%), other modes, e.g. trucks, pick-up vans, goods trains, bike, rented vehicles, etc. (6%) | [*Indicates relative reliance on different mode of travel]

- Proportion of workers who travelled alone: 13% (87% had either family members or other acquaintances accompanying them)

- Proportion of workers who received financial or subsistence support while returning: 11% (received financial help on the way), 44% (availed of free food provided by someone else)

- Proportion of workers who availed of support of government authorities while returning: 55%

Type of support received from govt. authorities: Free food (38%), health check-up (25%), transportation support (21%), shelter arrangement (11%), other support (5%)

- Proportion of workers who contacted an official helpline on the way: 15% (only 5.1% workers acknowledged receiving any support)

- Proportion of workers subjected to ‘isolation’ on the way: 32% (only 4% workers were isolated for at least 14 days. Average number of days of isolation was only 4 days).

- Proportion of workers subjected to ‘isolation’ after returning to village: 19%

Proportion of workers who were subjected to violence or humiliation after returning to village: 9%

- Proportion of workers who received support from the panchayat after returning to village: 34%

- Type of support received from panchayat: Free food (18%), separate shelter (43%), health check-up (32%), other support (7%)

- Proportion of workers having a bank account: 89%

Proportion of bank accounts of workers or their family members that received money from the govt. in the last one month: 39% [among recipients 25% got Rs. 500; 25% received Rs. 1000; 21% received Rs. 2000; rest of them received varying amounts]

- Proportion of workers or their families enrolled with various govt. schemes: targeted public distribution system (65%), farmers scheme (28%), employment guarantee (7%), insurance schemes (2%), others (7%).

- Glaring accounts of omission: None of the 60 surveyed workers were found registered under Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Fund. This calls for an important area of intervention.

- Proportion of workers whose family availed of public distribution system foodgrains in the current month: 57%

Proportion of workers who want to return to their worksites after the lockdown is withdrawn: 98%

Migrating for livelihood appears to be an unavoidable compulsion of millions of workers in states with low per capita income such as Uttar Pradesh. Migrant workers face a number of challenges in eking out a livelihood for survival, including low wages, inadequate savings, lack of job security and deprivation from basic amenities.

Persistent agrarian crisis and stagnation of the rural economy leaves no alternative for them other than returning to worksites located outside their home state every year despite the odds faced by them, evident in the aspiration of as many as 98% of interviewees who are keen to return to their places of work at the earliest possibility.

A comprehensive policy needs to be formulated to address the specific challenges faced by migrant labourers. Such a policy could provide for universalisation of entitlements over food subsidies, portability of entitlements across the country, extension of social security benefits for migrant workers, regulation of contractors and middlemen, measures for holding employers accountable for welfare of migrant workers, regulation of work conditions and arrangements for improving accessibility of shelter spaces and basic amenities, among others.