The vast plain in Mithilanchal (now a part of Bihar) wore a festive look despite the early hour. People had been gathering since the wee hours of the morning. Children wore their festive best while women, flowers in their hair and anticipation in their eyes. The air was redolent with the fragrance of the ceremonial fire and the aroma of roasting gram and fried sweets. Nearby, a magnificent horse bedecked with flowers pawed the ground impatiently.

It was the middle of the 12th century and celebrations were in full swing as Raja Gang Singh Dev was sponsoring a talaab.

A pond is built

The construction of a pond began with a sponsor- usually a member of the Royal family or merchant- who decided to construct a pond to gain some punya (blessing). He or she would delegate people to decide the site of the pond, get a priest to set an auspicious date, and announce the details to the surrounding villages. On the appointed day, an excited crowd would gather there, ready to work and socialise. Then would come the marking out of the pond. In the case of the 'ghod-dod' pond, one side of the pond would be fixed. With much fanfare, a horse would be brought to the pond site and made to run. The place at which it stopped running would be the length of the pond. Yes, 'ghordod' (ghod = horse and dod = run)means the length of a horse's run.

Several components make up the pond: the anganai or garden beside the pond, tatbandh or embankments, the inlet, and the outlet. All of these were carefully constructed according to laws set in books like the great Brihat Samhita . It wasn't just the structural elements, but also the biotic components of a healthy pond were factored in. After the pond filled up during the first monsoon, small silver figurines of various aquatic animals such as frogs, snakes and fish would be cast into the four corners of the pond as a plea to these creatures to make their home within it. More than functioning as an invite, this ritual served to remind everyone that the pond belonged to all. It also helped that ponds were always constructed to serve as a store of water and not for extractive uses such as fishing.

Gang Singh Dev constructed his talaab to ensure that his dynasty, which ruled Mithilanchal for 350 years, remained immortal. In this he suceeded, but he was not alone. Darbhanga has over 225 ponds, each of which has kept alive the name of its creator and the story of its creation.

Gang Singh Dev's talaab is now known as Ganga Sagar, Harahi ('with bones') is so called because an old skeleton was found there during excavation, Kunwari Diggi is still a 'kunwari' or a virgin because the sanctification ritual was never done, and so on. Sadly, in several cases, the knowledge associated with these magnificent structures has been lost over time.

Darbhanga's ponds today

Where earlier they were revered as stores of pristine water, today they are often polluted by sewage, mainly thanks to the Darbhanga municipality. Several sewage drains, including that of Darbhanga railway station are so constructed as to drain directly into the lakes.

While the importance of the anganai was once well known, today it it merely considered to be real estate as are the ponds themselves. There is a new and unfortunate trend of dumping debris into the lake and constructing houses on the land so formed. "Here", says Ranjit, a resident of a mohalla adjoining one such endangered pond, "it is the rich and well-connected who are the culprits. They alone have the power to render the law blind to their misdeeds. The buying of a small piece of land adjoining a lake, and gradually adding to it by dumping debris into the water is sadly, a far too common practice".

The people of Shahganj Benta, near Gami Pokhar attest to this. As little as 5 years ago, Gami Pokhar, a pristine pond built a 100 years ago a philanthropist known only as 'Gami', had three ghats - the northern for women, the southern for men, and the western for wayfarers. Today, it is encroached upon by several doctors' residences and clinics. The clinics dump medical waste into the river with impunity, which exposes the residents to a high risk of infection. Despite several protests and pleas, the municipality has continued to be blind to the state of these lakes.

The City Development Plan for Darbhanga allocated Rs.120 lakhs over the period 2011-13 towards the 'development of lakes as a secondary water source'. It is in the same period that the relentless encroachment and pollution of the lakes has intensified. Construction within ponds has been documented by the Talaab Bachao Abhiyaan and has intensified over the last 2 years.

Possible solutions

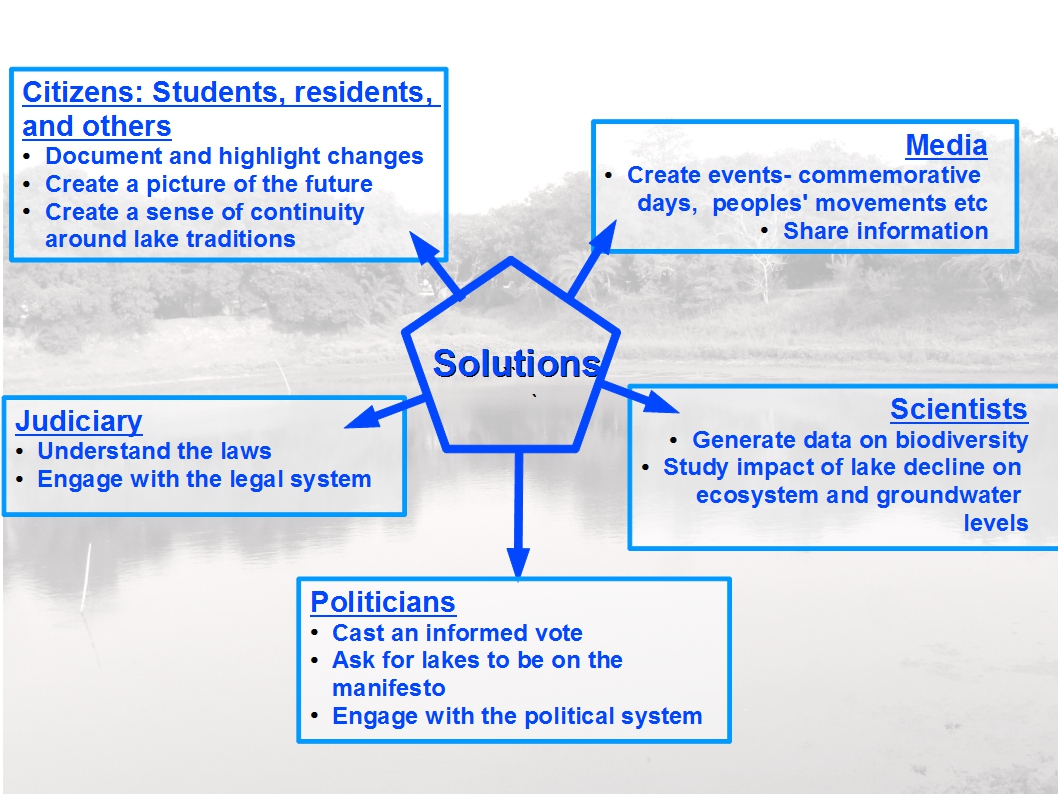

The 'power' factor is the reason that saving these lakes is not easy. In Darbhanga, as in other urban areas, the solution does not lie in 'a-one-size-fits-all-type' scientific and technical measures . One needs to enter the complicated and murky world of social and political solutions where no simple 'fix' can be applied. It is also tempting to only interact with those groups- residents, environmentalists and sympathetic media persons- that support the activist's agenda of protecting the ponds by stopping encroachment and pollution. However, a truly democratic process necessitates the involvement of all groups including politicians, municipal officials and the encroachers themselves, thus creating an iterative process of awareness-raising and consensus-building with all involved groups.

Local efforts kickstarted

The people of Shahganj Benta, Muhalla Dumdumma, Muhalla Kataharbari and many other small localities in Darbhanga are overcoming class and caste obstacles to question the rich who are taking away their ponds and the powerful who are permitting this theft. Dr. M.B. Verma regularly petitions the city authorities and alerts them to pollution and encroachment issues. The Mithila Gram Vikas Parishad has initiated the Talaab Bachao Andolan, which has for the last year, been on a crusade to rouse the city officials from their apathy and save the lakes for future generations.

The response has been mixed. As the members of the Andolan told me, whenever they go to the politicians and bureaucrats, they are heartily congratulated on the "good work they are doing" but nothing tangible comes out of those meetings. The Andolan has presented two memoranda to the government, in 2013 and again in 2014. These list some simple demands that will save the ponds, but have not been acted upon.

On the other hand, the poor of Darbhanga cannot afford to look upon the lakes as dumping grounds and real estate. As a resident of Shahganj Benta, who only wished to be identified as Anil's mother told me, "If Gami Pokhar becomes dry, what will happen to us?"

View images of the lakes of Darbhanga and the struggle to keep them alive.