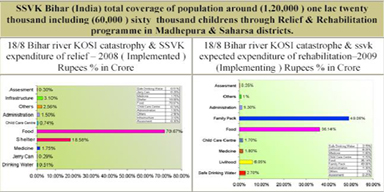

The following article is the latest update of an overview of Kosi floods by SSVK. It reveals the ineffective handling and inadequate supply of materials by the Government in the flood hit regions. It also points out the activities done by various organizations and SSVK itself. Tabular columns illustrate the actual status of badly affected areas, relief camps, number of fatalities and the supply of materials. The report instructs on how to react to such unfavorable conditions in the future.

The Incidence

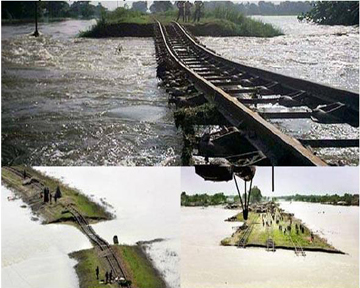

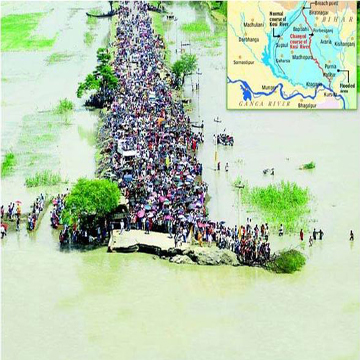

A human tragedy of unparalleled dimensions unleashed itself on millions residing in the 7 North Bihar Districts of Supaul, Araria, Madhepura, Saharsa, Purnia, Khagaria and Katihar due to a breach in the in the eastern Kosi embankment upstream of the Indian border at Kushaha in neighbouring Nepal on the 18th of August, 2008. Following the breach, River Kosi, often referred to as the “sorrow of Bihar”, picked up a channel it had abandoned over 200 years ago, drowning towns and numerous villages coming in the way of its newly acquired course, affecting more than 3 million people. Still worse this altered course now cuts through an area which ever since the construction of the eastern Kosi Embankment almost 5 decades ago had lived in the relative comfort of being flood protected. Unlike floods, this is not calm water but an angry torrent, making relief work very difficult.

The Impact

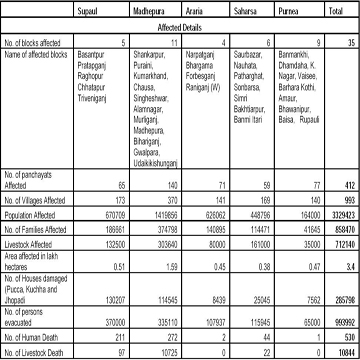

With the river virulently flowing through its new found course, lakhs of people were caught unawares. Apart from loss of land, crops, homes, human and livestock lives and massive damage to infrastructure; close to a million found themselves marooned . According to a release of the Disaster Management Department of Government of Bihar dated 21/01/09, the following is the eventual status of the impact of floods in the 5 worst affected districts: Source: Disaster Management Department, Govt. Of Bihar Website: http://disastermgmt.bih.nic.in/ In government statistics death figures are grossly under reported. Reports from field workers of ActionAid and other organisations participating in the Citizen's Initiative on Flood in Bihar, place death estimates at 2,000. Media reports estimate still higher figures. Government figures are much lower because they only include those whose bodies which have been recovered.

Response of the Government

Caught unawares by the magnitude of the tragedy, it took the government almost 10 days to come forth with a structured response to the daunting task of evacuating more than a million marooned, a task which lingered late into the 2nd week of September 2008. Having got its act together, it next set about addressing the issue of running relief operations for the evacuated and the displaced by setting up relief camps and health and veterinary centres. It certainly goes to the credit of the Government of Bihar that it did not fight shy of the enormity of the task that it was confronted with. Ministers of the Bihar Cabinet were specifically designated to the worst affected districts to oversee the rescue and relief operations. Special District Magistrates were posted to the affected districts for smooth coordination of relief and rescue operations and a host of relief interventions were initiated. Government for the first time came up with mega relief camps with more structured provision of food and basic services like health, drinking water and sanitation. Nevertheless, the enormity of the task placed it beyond the resources the state government had at its command. Even at its peak the relief operations fell far short of the demand with the government run relief camps accounting for less than 10% of the affected population and the rest living in unorganized clusters on embankments, by road sides or on elevated open grounds on their own. Worse, the state government had neither the manpower nor the resources to meet this unprecedented situation. Instances of food riots breaking out at relief camps and relief materials being looted in transit were reported in the media. Supplies, inadequate to the demand, impacted most severely on the already socially excluded victims particularly the Dalits who were deprived of their relief entitlements by the dominant castes as well as by an apathetic lower bureaucracy. Cramped and unhygienic conditions on limited dry ground resulted in outbreak of diseases. With the crisis still far from over the government began rolling back its relief camps substituting them with gratuitous relief (GR) in grain and cash doles.

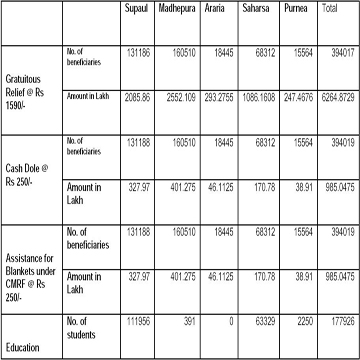

The following table is illustrative of the government support that followed: Bihar Government Assistance to the Kosi Flood Victims

Source: Disaster Management Department, Govt. Of Bihar

While the extent to which GR and cash doles were made available by the government is praiseworthy, its relevance in the context of the present crisis raises questions. With their habitations lost to or yet to recover from the submergence, their livelihoods and assets lost and with their dwellings barely providing some cover to pass off for a makeshift shelter, the relief camps needed to be run for longer for the flood victims. Worse still, closure of the relief camps during winter has left the flood victims to suffer in extreme cold conditions. Many families are putting up in makeshift bamboo and straw shelters near Gwalpara in Madhepura district. Many who returned to their homes after the water receded have discovered that it has left the land swampy, making the rebuilding process difficult, if not impossible. Even if government assertions of plugging the breach and restoring the river to its pre-breach channel are to be believed, it still entails a minimum wait time of 3 to 4 months for them. Till then the relief camps should have been run. The Nitish government, which had made elaborate promises of providing food and shelter to the flood victims for “as long as required”, has instead washed its hands off the situation and reportedly ordered closure of the camps after providing some support as indicated in the table above.

Though the Bihar Government has not been entirely callous, the implementation at the local level has left a lot to be desired. For instance, while the state Government allocated funds for rebuilding of hutments in many flood-affected districts, the authorities wasted more than three months in reaching out to the victims. Even those who have fortunately received government assistance for rebuilding their homes are equally crestfallen because of the inadequate relief. The chief minister has no doubt sought additional financial assistance from the Centre for massive reconstruction and rehabilitation efforts. To begin with, Nitish wants Rs 1.5 lakh for every house destroyed in floodwater.  The Centre, however, has remained silent after initially granting Rs 1,010 crore for relief efforts. Meanwhile, the survivors are fighting misery on several fronts. For one, there have been a series of boat mishaps in almost all flood-affected districts because the locals are now forced to board rickety, makeshift boats to reach destinations, as the Kosi floods have washed away dozens of bridges, culverts and link roads. Even months after the breach in the Kusaha embankment in Nepal that caused the flood disaster, the state Water Resources Department (WRD), which is responsible for maintaining and repairing the embankment, is yet to plug it. The writing is already on the wall with the WRD imposing a penalty of Rs 10 lakh on Vashishtha Construction Company last week, for failing to complete the pilot channel and cofferdams at Kusaha by December 15 last year.

The Centre, however, has remained silent after initially granting Rs 1,010 crore for relief efforts. Meanwhile, the survivors are fighting misery on several fronts. For one, there have been a series of boat mishaps in almost all flood-affected districts because the locals are now forced to board rickety, makeshift boats to reach destinations, as the Kosi floods have washed away dozens of bridges, culverts and link roads. Even months after the breach in the Kusaha embankment in Nepal that caused the flood disaster, the state Water Resources Department (WRD), which is responsible for maintaining and repairing the embankment, is yet to plug it. The writing is already on the wall with the WRD imposing a penalty of Rs 10 lakh on Vashishtha Construction Company last week, for failing to complete the pilot channel and cofferdams at Kusaha by December 15 last year.

The delay, however, has cast a shadow on the repairing of the Kusaha embankment before the March 31 deadline. Clearly, the WRD does not seem to have learnt its lessons despite apparently being guilty of the callousness and neglect that made the Kusaha breach and the subsequent flood. Now with relief off the government’s agenda; resettlement and rehabilitation policy still in the offing and its translation into ground reality at least a couple of months away; people having lost opportunity of any gainful employment in agriculture; their asset base eroded; their shelter in shambles; the education of their children hampered; their vulnerability to health hazards accentuated and with winter turning incrementally severe; the flood affected, particularly the socially excluded and the vulnerable groups, continue requiring immediate assistance, which, apart from private players, does not appear forthcoming from any other quarter. Even among the private players (NGOs, NGO donors, faith based organizations and corporates) not many are left around and of the few that are there, most have their resources geared up for undertaking rehabilitative interventions.

Response of SSVK in the current crisis

SSVK till date has run 4 relief camps in Murliganj block of Madhepura district with support from N.M. Budhrani Trust, 8 relief camps in Kumarkhand Block of the same district with support from United way Mumbai and 2 relief camps in Patarghat Block of Saharsa district with support from Swiss Red Cross. Through the four camps in Murliganj Block supported by N.M. Budhrani Trust, 1,632 families were covered. At all these camps community kitchens serving 2 cooked meals a day were run. 7 hand pumps were installed to address the drinking water needs and SSVK’s trained cadre of health workers addressed the health needs of the affected families. All families were also provided with shelters in the form of polythene sheets measuring 15 feet by 12 feet.. Biscuits and milk with sugar were provided to the children. Gas lamps were provided to keep the camps lighted during night. These camps were run over a seven week period till the last week of October 2008.

All India Disaster Management Institute also chipped in its support through sponsoring the nutrition component at one camp for two weeks. UNICEF also extended its support at these 4 camps which, apart from provision of Halozene tablets, bleaching powder and polythene sheets, also incorporated training of 23 health volunteers in carrying out special supplementation programmes of administering Vitamin A supplementation to 700 children in the age group 9 months to 5 years, deforming dose to 705 children in the age group 2 to 5 years and IFA supplementation to 53 pregnant women, 292 lactating mothers and 279 adolescent girls. SSVK out of its resources ran a child care centre at each of these 4 camps for a wide variety of purposes including games, tuition classes, peer activities and pre schools. These centres continue to this day although they have been relocated to the villages from which the beneficiaries came. Assistance from United way Mumbai for Kumarkhand was operationalised through organizing the targeted 4000 families (4038 actually covered) with a total population of around 20’500 into 8 relief camps. Though the needs were manifold, the intervention was prioritized and confined to addressing the food, drinking water, shelter and health related needs of the people in light of the limited resources available for the moment and extended over a one month period from October 19, 2008 to November 17, 2008. The intervention accounted for one wholesome meal a day through setting up of a community kitchen at each camp. The cooked meal consisted of rice, pulse and one vegetable. Community kitchens were preferred over dry ration support as the latter left the beneficiaries with the difficult, if not impossible, choice of arranging for fuel. Moreover, the engagement of the victims in various tasks associated with running the community kitchens helped maintain a modicum of community conviviality which also helped the victims in overcoming their enormous grief.

At each camp provision was also made for one hand pump and five water storage containers to address the drinking water needs and prevent the outbreak of water borne diseases. All the 4000 families were provided with a polythene sheet measuring 15 feet by 12 feet to account for their shelter related needs. The distribution of the polythene sheets was done against production of the token that was issued to the 4000 families. At each camp provision was also made for 2 gas lamps to keep the site illuminated during night thus ensuring greater safety of the residents. Additionally 4 torches were provided per camp for running errands after dark. The intervention also provided for medical relief and assistance. Having run a community health programme in the past, SSVK’s trained cadre of community health workers adept in symptomatically diagnosing the commonly occurring health problems during floods addressed the heath needs of the affected families. 2 health workers, 1 in charge of 4 camps were responsible for addressing the health needs. UNICEF once again chipped in with its support which incorporated training of 39 health volunteers in carrying out special supplementation programmes of administering Vitamin A supplementation to 1626 children in the age group 9 months to 5 years, deworming dose to 1754 children in the age group 2 to 5 years and IFA supplementation to 244 pregnant women, 428 lactating mothers and 523 adolescent girls. In Kumarkhand again, SSVK out of its resources ran a child care centre at each of these 8 camps for a wide variety of purposes including games, tuition classes, peer activities and pre schools. These centres continue to this day although they have been relocated to the villages from which the beneficiaries came.

Assistance from Swiss Red Cross for Patarghat block was operationalised through organizing the targeted 1000 families (1012) actually covered) with a total population of around 4’956 into 2 relief camps.  Though the needs were manifold, the intervention was prioritized and confined to addressing the food, drinking water, shelter and health related needs of the people in light of the limited resources available for the moment and extended over a 15 day period from November 19, 2008 to December 3, 2008. The intervention provided for two meals a day, one in the form of dry ration support of flat rice and jiggery to account for breakfast and the other in the form of cooked food comprising rice, pulse and a vegetable to account for at least one wholesome meal through setting up of community kitchens. Community kitchens were preferred over dry ration support as the latter would have left the beneficiaries with the difficult, if not impossible, choice of arranging for fuel. Moreover, by engaging the victims in various tasks associated with running the community kitchens helped maintain a modicum of community conviviality which also helped the victims in overcoming their enormous grief.

Though the needs were manifold, the intervention was prioritized and confined to addressing the food, drinking water, shelter and health related needs of the people in light of the limited resources available for the moment and extended over a 15 day period from November 19, 2008 to December 3, 2008. The intervention provided for two meals a day, one in the form of dry ration support of flat rice and jiggery to account for breakfast and the other in the form of cooked food comprising rice, pulse and a vegetable to account for at least one wholesome meal through setting up of community kitchens. Community kitchens were preferred over dry ration support as the latter would have left the beneficiaries with the difficult, if not impossible, choice of arranging for fuel. Moreover, by engaging the victims in various tasks associated with running the community kitchens helped maintain a modicum of community conviviality which also helped the victims in overcoming their enormous grief.

At each camp provision was made for five hand pumps each and five water storage containers to address the drinking water needs. Additionally each family was provided with a plastic jerry can of 5 litre capacity to take care of drinking water storage and ensuring water security at the household level. All the 1000 families were provided with a polythene sheet measuring 18 feet by 12 feet to account for their shelter related needs. At each camp provision was made for 4 gas lamps to keep the site illuminated during night thus ensuring greater safety of the residents. Additionally 4 torches were provided per camp for running errands after dark. The intervention also provided for medical relief and assistance. Having run a community health programme in the past, SSVK’s trained cadre of community health workers adept in symptomatically diagnosing the commonly occurring health problems during floods addressed the heath needs of the affected families. 2 health workers, 1 in charge of each of the 2 camps were responsible for addressing the health needs. Food related interventions came as a critical input to enable the beneficiaries to tide over a period when floods had left them bereft of any livelihood opportunities to sustain themselves and they were on the threshold of starvation. Moreover it prevented them from getting deeper into the debt trap as with food assistance they did not have to depend on the moneylenders for the same. The interventions could provide them a measure of food security and were appropriately timed as they came when relief assistance from the government was as yet to reach the victims. The installation of new hand pumps ensured access of the target group to clean and safe drinking water. The availability of safe drinking water reduced the vulnerability of the target group by acting as a check on incidence of morbidity. For the entire period of relief operations, no significant outbreak of any water borne epidemic was reported from the field.

Provision of polythene sheets gave them shelter against the vagaries of nature

Medicinal Assistance was extended for flood induced diseases like diarhhoea, fever, gastroenteritis, abdominal pain, deforming, acidity, cold and cough, pneumonia, skin and eye infection and malaria. This intervention provided much needed medical succor to the flood victims. In pattarghat (Saharsa) again, SSVK out of its resources ran a child care centre at each of these2 camps for a wide variety of purposes including games, tuition classes, peer activities and pre schools. These centres continue to this day although they have been relocated to the villages from which the beneficiaries came. Other like Tech Mahindra, PRAYAS, Goonj and Unitedway Mumbai and many individuals also extended support in kind. Currently SSVK continues running its health intervention and child care centres with relief assistance from Saffron Art, a leading auctioneering house of high end paintings, through which a set of 31 painters pledged the proceeds of the auction of their paintings specially held for the Kosi cause. Proceeds from 17 of the 31 paintings came to SSVK to be used specifically for the Kosi flood victims. SSVK has also been part of the Dalit Watch initiative which has came out with a report on the systematic exclusion of Dalits from the relief initiatives of the government. The support for bringing out the report came from CORDAID. SSVK has dedicated a space on its web site that consistently updates media reporting on floods, has articles, reports and documents on floods and provides important links to sites of consequence. Kindly visit us at www.ssvk.org or http://www.ssvk.org/koshi.htm

Future directions

Given the nature of deluge, it was quite evident rather early that evacuation, immediate and intermediate relief assistance was just the tip of the efforts that would eventually have to be taken up. Experts quite early suggested that it was just the beginning of the problem, for one, the changed course of the river had swallowed large swathes of land which were hardly going to resurface even after the water receded. Two, these inundated areas were technically in the river bed, thereby completely uprooting those living in these areas—not to talk about the loss of agriculture land, houses, livestock, ponds, wells and above all their dreams. The state government has sought an assistance package of almost Rs 9,000 crores from the central government for rehabilitative initiatives over and above the Rs 1010 crores initially sanctioned by the Prime Minister towards relief. Mr. S.C. Jha, member of PM’s task force on Bihar is however of the opinion that rehabilitative interventions would require somewhere between twenty five to thirty thousand crores.  SSVK volunteers in a meeting in child care centre run by SSVK in Murliganj district, Madhepura Thus a daunting task awaits in terms of reconstruction of houses and rehabilitation of livelihoods of those affected by the Kosi Floods. Apart from restoration of public infrastructure like roads, railways, bridges and government buildings, there is the mammoth task of reconstruction and repair of fully and partially damaged houses in the flood affected villages and making them into habitable settlements by rebuilding community infrastructure like roads, library, and drinking water and sanitation facilities. Keeping in mind the scale at which a demand for construction workers would be required, there would be a need to train local people in masonry and other construction related skills. This would also generate employment for the communities during the reconstruction phase. There would also be a need to build local management capacities to facilitate better management and utilization of the community structures created through the project. Restoring houses without providing for livelihoods would make people migrate for livelihoods. The floods have left the victims homeless, destitute and without any source of income or livelihood. The only way then to ensure their stay and repair the fragile rural economy is to simultaneously, along with rebuilding of houses, provide them with income generation opportunities right at the village level. Hence, along with reconstruction of the damaged houses, it becomes imperative to lay an equal emphasis on an integrated and sustainable revival of livelihoods in order to turn the tragedy into a livelihood opportunity. For the restoration of livelihoods, the thrust would have to be both on the farm and non farm sector.

SSVK volunteers in a meeting in child care centre run by SSVK in Murliganj district, Madhepura Thus a daunting task awaits in terms of reconstruction of houses and rehabilitation of livelihoods of those affected by the Kosi Floods. Apart from restoration of public infrastructure like roads, railways, bridges and government buildings, there is the mammoth task of reconstruction and repair of fully and partially damaged houses in the flood affected villages and making them into habitable settlements by rebuilding community infrastructure like roads, library, and drinking water and sanitation facilities. Keeping in mind the scale at which a demand for construction workers would be required, there would be a need to train local people in masonry and other construction related skills. This would also generate employment for the communities during the reconstruction phase. There would also be a need to build local management capacities to facilitate better management and utilization of the community structures created through the project. Restoring houses without providing for livelihoods would make people migrate for livelihoods. The floods have left the victims homeless, destitute and without any source of income or livelihood. The only way then to ensure their stay and repair the fragile rural economy is to simultaneously, along with rebuilding of houses, provide them with income generation opportunities right at the village level. Hence, along with reconstruction of the damaged houses, it becomes imperative to lay an equal emphasis on an integrated and sustainable revival of livelihoods in order to turn the tragedy into a livelihood opportunity. For the restoration of livelihoods, the thrust would have to be both on the farm and non farm sector.

Key intervention areas for the farm sector

• Agricultural input support for those whose land has been spared from being devoured by the river to be able to undertake rabi cultivation

• Promotion of short duration crops on fields where crops have been entirely lost

• Reclamation of sand cast and waterlogged fields

• Promotion of pisciculture and makhana cultivation

• Restoration of livestock. For the non farm sector emphasis would have to be laid on:

• Livelihood diversification through promotion of non-farm employment opportunities

• Income enhancement through promotion of new skills particularly in the construction sector and up gradation of existing skills, organization of beneficiaries into self help groups and provision of working capital support to them through creation of a revolving fund and promotion of secure and competitive market linkages

• Securing the entitlements of the landless and the marginalized in the employment generation oriented programmes of the government like NREGA and PMGSY and enhanced allocation under various schemes of the government. Another key intervention would be to reduce the vulnerabilities of rural communities to disasters and stresses through building community level capacities in disaster preparedness and mitigation. However, a detailed intervention design for reconstruction and livelihood restoration, is contingent on the reconstruction and resettlement policy which has recently been brought out by the Government of Bihar. This document sets the broad contours of the reconstruction and resettlement approach that is to follow and addresses issues like:

Approach to housing

Models of public private partnership that the state government opts for

- Compensation packages on offer from the government

- Resettlement of those who have lost their land to the Kosi

- Construction parameters for the dislocated including plot size, built up area and technical parameters for rendering the houses hazard proof

Parameters for in situ reconstruction

• Government’s stance on livelihood restoration and the contingent macro policy it evolves for the same (e.g. cluster approach, enhanced allocations within existing schemes, agricultural subsidies, relaxation of norms under SGSY) all of which would have implications for fine tuning our intervention.

• Specific roles for specific stakeholders Currently work is on the specifics of the state policy to make it operationally viable at the ground level.