The earliest known civilizations settled around rivers as they provided access to the water needed for cultivating crops. Over time, humans learnt to control the flow of water by the construction of barriers across the direction of the river flow. Today, most countries in the world have mammoth dams over 150 metres in height, which have been built to store huge amounts of water at the cost of submerging and displacing a large population that lives in the catchment area of the dams. Another risk of creating such gargantuan structures is the vulnerability of these structures to extreme events such as floods.

The negative social and environmental impacts of large dams have been acknowledged the world over. Despite the fact, the governments around the globe are smitten by them. India is the fourth largest dam builder in the world with 4710 completed large dams. However, the country performs poorly, when it comes to the provision of irrigation through the vast canal infrastructure at its disposal. Canals irrigate less than 25% of India’s net irrigated area (Irrigation, 2010).

Another problem of the dam-canal model is the exclusion of upstream and remote tribal drylands and worse still is their displacement due to the submergence of villages in the dam command area. According to a report on displacement, 16.4 million people have been displaced by 3030 medium and large dams and tribals account for over 40% of the displaced population (Negi & Ganguly, 2011).

Check dams - a better approach

A viable solution to this problem is village-level water harvesting and storage through the construction of small dams or check dams. Check dams are small barriers constructed using stone, cement or concrete, built across the direction of river flow on a rivulet or stream to harvest rainwater (Development Alternatives, 2003). Check dams built in a series over the entire length of the river and its tributaries have greater storage and harvesting potential compared to a large dam. According to groundbreaking research by Michael Evenari, a micro catchment can harvest 15.21% of rainwater, while a medium dam can harvest only 3% of the rainwater. (Centre for Science and Environment, 2011).

This article shares the experience of the NM Sadguru Water and Development Foundation in providing irrigation to tribal drylands of Dahod district through the construction of check dams in a saturated approach.

Lift irrigation cooperatives water upstream fields

N M Sadguru Water and Development Foundation was founded in 1974. One of their key aims was to improve the agriculture productivity of tribal farmers of Dahod district. The region was then bereft of any flow surface irrigation schemes. Also, as the terrain was undulating, most farmlands were located at a height from downstream rivers making canal irrigation infeasible.

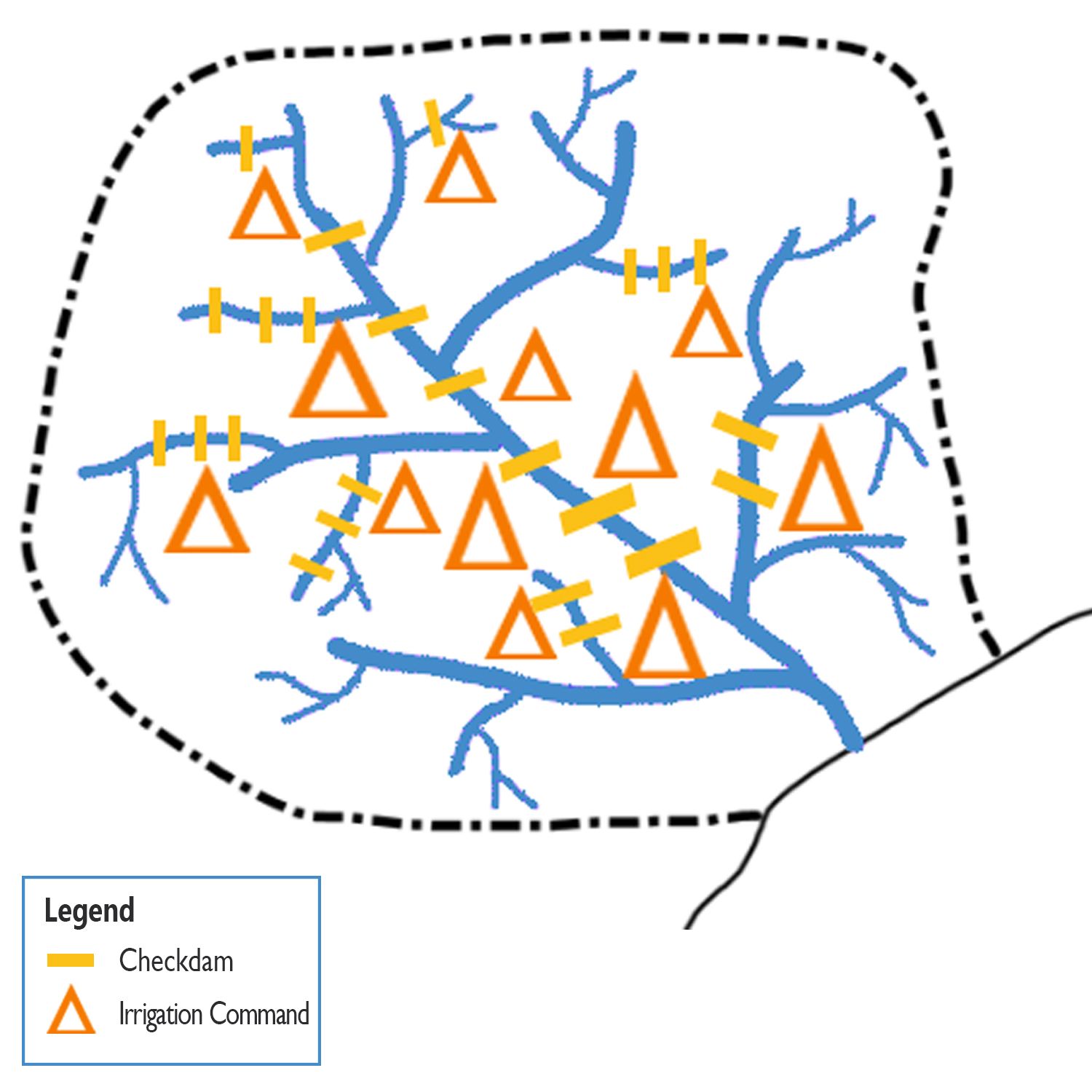

The organisation initiated work by creating distributed storages in the form of check dams constructed in a series on big and small rivers; Khan, Kali, Machhan, Hadaf and Panam of Dahod. They installed lifting infrastructure in the dam commands to provision water to uphill farmlands. These lift irrigation systems are managed by cooperative societies to enable community-led management and control of water harvested.

The key elements of their work approach are below:

- Creating water harvesting potential along the length of the river through series of water harvesting structures/check dams

- Lift Irrigation Cooperatives (LIC) established to sustainably harvest the stored water for irrigation in the command area

The organization initiates work only after the demand for such work is raised by the community. N M Sadguru Foundation submits the construction plans under various tribal development and irrigation schemes of the government. Post-approval of funding, the construction of check dams takes place and installation of lift irrigation system is done. The community is involved in the entire planning process. Beneficiary farmers set up a lift irrigation cooperative to take over the water distribution and management post-installation of the lift irrigation system. This ensures that the community is an active participant in the process rather than a passive recipient.

The impact

The saturated approach of the organisation has led to the creation of storage potential of 41 MCM (Million cubic metre) through the construction of 221 check dams in Dahod district. This work has led to Dahod becoming one of the best-irrigated districts in the state from a water-scarce one. The cropping intensity of the region where Sadguru’s work is concentrated is 1.96, while the overall cropping intensity of Dahod is 1.40.

Cumulatively, 431 masonry water harvesting structures have been executed by Sadguru Foundation over the last 50 years which have the potential to irrigate 61,866 acres thereby benefitting 29,396 households. 440 community lift irrigation schemes have been executed by the organisation having a command area of 56,440 acres which are fully managed by Lift Irrigation Cooperatives.

Scale-up potential

Water harvesting using check dams built in a series has the potential to transform the drylands into productive agricultural fields, sustain ecology and even revive rivers during the dry season. The structures can be planned across both major and minor river basins of the country, to allow for equitable distribution of benefits to both upper and lower catchment populations.

Existing government schemes and programmes offer good potential for scale-up in various states. These structures can be included under Tribal Sub Plans, Tribal Area Development Plans, MGNREGS, Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY), Tribal Development Fund and other projects under NABARD, etc.

This case is part of the ‘Compendium of Best Practices: Water Management in Tribal areas’, a document developed by AKRSP(I) and Axis Bank Foundation (ABF).

Author: Anjali Aggarwal is a researcher with seven years of experience in documenting and understanding the change brought by grassroots organizations working in rural parts of India. An alumnus of the Indian Institute of Forest Management, her interest areas are Conservation, Livelihoods, and Education. She likes bird watching and having a dialogue with rural community members.