Visitors and the Uttarakhand Tourism Department liken the mountain to 'devbhoomi' or the heavens but it isn't often that a villager of the area echoes those sentiments. Most of them are weary of the unending struggle to live in harmony with those steep slopes that make all manner of infrastructure difficult.

That is why the villagers of Indwal Grampanchayat come as a welcome change. 'Yeh to Jannat hain' one of them told me. "This is heaven".

Looking around, I had no option but to agree. I was sitting on a breezy balcony overlooking the valley. In my hand was a glass of cool water that I knew was absolutely safe to drink. An old man irrigated his potato fields from a tank filled to the brim with sparkling water. Further off were fields of onions and capsicum. I was in the 'vegetable belt' of Tehri Garhwal- the area that supplies Delhi with its vegetables.

Indwal Panchayat is a group of five villages scattered in the upper reaches of the river Henwal that flows in the district of Tehri Garhwal in Uttarakhand. The area is developing a reputation as a producer of peas. Green peas are grown by nearly every farmer in the village. This 60-day crop, planted every spring, earns each farmer an average of Rs.40,000 per year. The farmers are nearly without exception, quietly buoyant with hope and tension-free about their water situation.

Households are just as free from water-worries. The Panchayat boasts a supply that Delhi would envy. Each household receives flowing water in their taps 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Each drop of this water is treated and is bacteria-free. Despite the fact that some of these taps source water from springs called 'Lal Pani' (red water) for their high iron content, the water that reaches the houses is sparkling clean and pure. There is a parallel irrigation system that reaches most houses; incredibly enough, a large proportion of this water is treated and safe to drink too.

A different story 5 years ago

It wasn't always like this. Just five years ago, the residents of Indwal were hard pressed to quench their own thirst, let alone that of their crops. Women routinely walked all the way down to the river and then back up- an altitudinal change of more than 400 metres- carrying water on their heads. When this proved to be too much, they began employing mules. This would need an outlay of about Rs. 200 per familiy every 3-4 days, far more than these subsistence farmers could afford.

The fields fared no better, either. The crops grown were largely rainfed wheat and maybe some millets. When the yields would barely satisfy the families' needs for a part of the year, marketing was out of the question. Most of the men worked as labourers- when and if they could get work.

What caused the shift?

In 2005, Madanlal was elected to the post of Pradhan. He was then, and remains now, a muleteer and farmer. His background meant that he knew the importance of water. Since being elected to the post, Madanlal has been working with a single-point agenda- that of supplying water to his village.

Madanlal first began with the construction of a few tanks to collect water for irrigation. Money for these was obtained from the Horticultural Department. After this, it was the domestic water supply system's turn.

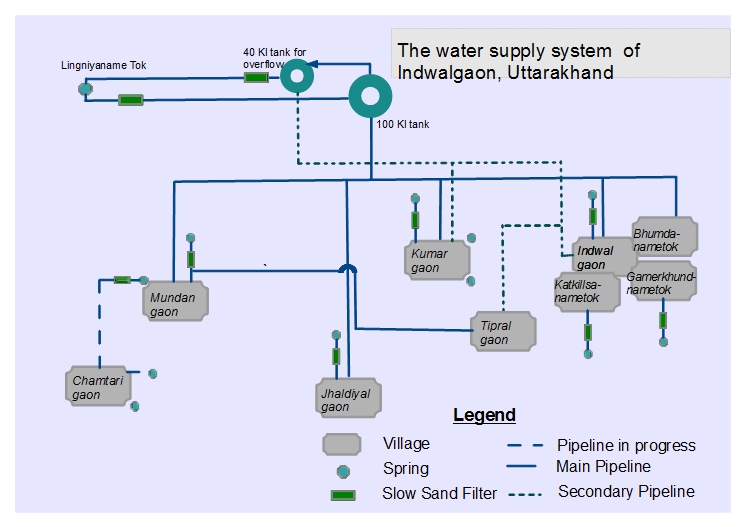

Earlier, Indwalgaon and Kumargaon were supplied water from a perennial spring at Lingiyaname tok. Water from the spring was brought via a 15mm diameter pipe to a tank with a capacity of 40,000 litres. Madanlal completely overhauled the system. The villages now boast of a 1,00,000 litre capacity tank with pipes of sufficient diameter. Using 'shramadaan' or voluntary labour to offset labour costs, Madanlal managed to purchase nearly twice the length of the pipeline accounted for. He has kept meticulous accounts, including that of the outlay for 'necessary hospitality' exerted towards visiting officials.

The old tank and pipes were not allowed to slowly decay as is the norm elsewhere. Instead, they were patched up. It now collects the overflow from the new one and takes it to three hamlets. The overflow from this tank is further collected into an unlined tank and used to water cattle and recharge the groundwater.

Madanlal did not stop there. Using resources from various Government Departments and schemes, he carried on building water storage tanks. Today, the households of all but one of the hamlets of Indwalgaon have at least one source of piped water supply to their thresholds. All this water passes through a slow sand filter before entering the distribution system. A slow sand filter and tank is currently being built in the last remaining hamlet of Chamtari.

Chamtari is the Dalit hamlet of the village. It's being the last hamlet to be included in Indwal's water supply system is a sad comment on the pervasiveness of social exclusion even in otherwise progressive communities.

Indwal's starting point was no better, and probably a lot worse, than that of other villages- a few trickling springs, far flung hamlets and an altitudinal range of 300 mts. No special funds were made available to the villagers. The infrastructure was built using the funds available to all Gram Panchayats through national schemes.

Indwal's starting point was no better, and probably a lot worse, than that of other villages- a few trickling springs, far flung hamlets and an altitudinal range of 300 mts. No special funds were made available to the villagers. The infrastructure was built using the funds available to all Gram Panchayats through national schemes.

The difference between Indwal and other villages is that very few Pradhans seem to utilise these funds. Madanlal does not see any difficulty at all in getting this information. He says that there is a monthly meeting for all Pradhans in every block. This is attended by officials from 'all possible' departments- water supply, electricity, horticulture, animal husbandry, etc. Plans are discussed for the benefit of the Pradhans.

But only one among them took copious notes and that's paid off for Indwal.