Guset post: Amita Bhaduri

Source: Excreta Matters, Centre for Science and Environment, 2012

The report attempts to find answers to how should the country manage its water needs so that it does not drown in its own excreta. The question is not just about water, pollution and waste but about the way Indian cities will develop and more generally about a paradigm of growth that is sustainable and affordable.

The report which sought to understand the political economy of defecation – where the rich are subsidized to excrete in convenience, warns that “if we do not change our ways, we will deliberately murder more rivers, lakes and water bodies. We will then be a generation that has not only lost its rivers, but has committed deliberate hydrocide.”

The two volume report that took three and a half years of research, includes surveys on water and waste water management in 71 cities in India, and presents an assimilation of the survey's results.

Volume I (296 pages) dwells on how urban India is soaking up water, polluting rivers and drowning in its own waste while Volume II (496 pages) contains a very detailed survey of 71 cities, and presents an assimilation of the survey's results. The city-by-city excreta-sewage-pollution tales are presented region-wise such as cities from the Himalayas, Indo-Gangetic Plains, Deccan etc.

Chapter 1 titled “Pipe dream” deals with how the country’s water allocation balance is beginning to be skewed by the country’s relentless urbanisation and industrial growth. The competing demand for water is turning this resource into a basis for conflict. City administrations are opting for a supply-and-supply-more style of water provision. Such a choice, causes them to look for water sources further and further away, and bring water by using pipelines that are becoming longer, and hence more difficult to manage.

It discusses the flash points because of inter-sectoral water allocation issues and how every city’s water imprint is getting bigger and longer. It concludes that “cities will have to join the dots, and learn the connection between their water and the environment from where it is sourced.” The gross guesstimate that exists for urban India’s water supply figures is made on the basis of demand, on present and projected populations and assumes supply matches demand. There is little information on how much water cities are supplied with and use.

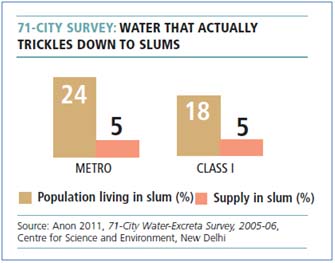

The report focuses on the grim inequity marked by huge gap in water supply within the city and suggests that the challenge is as much about justice as about technology. “If the technology for water and waste in the city is expensive, supply and sewerage facilities can only be provided to some and not all.”

Source: Excreta Matters, Centre for Science and Environment, 2012

There are large quantities of missing water in distribution (40 per cent and more) and the report suggests that the real gap is not between demand and supply but between supply and supply.

Chapter 2 titled “Hurtling into the aquifer” deals with the problem of groundwater extraction, both formal by water agencies and informal by households. The report states that “when water agencies hike water tariffs, commercial establishments quietly shift to the informal water economy also predicated on groundwater extraction.

At present, the chapter emphasizes that the groundwater levels in the cities are plummeting and city administrations have neglected the water bodies which used to serve the aquifer-recharge system. The disappearance of these sponges of the city has exacerbated floods and sharpened the pain of drought. The report also argues that there is an urgent need to investigate and map real-time groundwater use in the cities.

Chapter 3 on “The water-waste connection” looks at the journey of excreta, from generation via conveyance to disposal. It reveals how within cities only a minority has access to water and sewerage systems. Sewage treatment plants (mostly unused) are concentrated along a few rivers, mostly in metro cities.

The disconnect between water supply and sewage management has resulted in pollution with the result that the country is drowning in its own excreta. For much of urban India, the only option is open defecation – which does not pollute the waterways because very little water is used here, but has terrible public hygiene and health impacts.

The example of Pune’s sewage system is cited where the city has put strenuous efforts to build underground conveyance systems and has covered as much as ninety per cent of the city’s area. Yet, the city’s river Mula-Mutha continues to be a sewer, as the city’s sewerage output, has been grossly underestimated. As a result, a large proportion of the sewage is not trapped and treated and so it simply makes its way to the river directly, which ironically carries treated water from the sewage treatment plant located upstream.

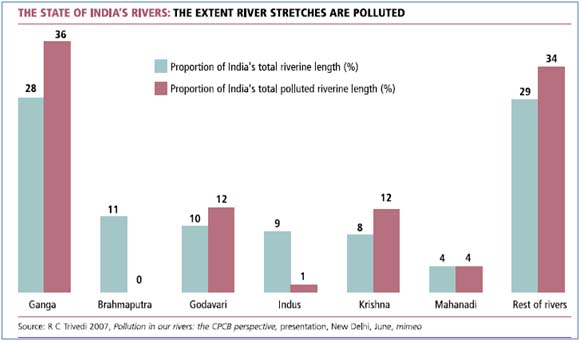

Chapter 4 on “The real excreta of progress” notes how the ‘flush-and-forget’ approach to excreta management is especially unsustainable today because rivers are losing their flow. Dammed today all the way from head-water to sea, rivers’ ability to assimilate waste has drastically reduced.

Source: Excreta Matters, Centre for Science and Environment, 2012

It points out that huge investments have gone into river and lake cleaning programmes and in sewage infrastructure, yet rivers continue to turn into sewage canals. More and more clean water must be brought in from further and further away, at greater expense.

The chapter outlines how governments do not charge for the water supplied, or for the waste collected or treated. The relatively rich users of this system are then the ones that receive a massive subsidy, this time to defecate.

The country’s double burden of pollution (traditional-bacterial and heavy-metal modern) and diseases (traditional water-borne and chemical-induced) to treat, is dealt with. The technology and cost of water treatment depends on what is being cleaned.

More importantly, the report states that it is the lack of water in ecosystems that is making the task of pollution control even more difficult and expensive. With rivers losing water to dams and hydroelectric projects in its upper reaches and then to agriculture, industry and cities downstream, there is little ability left in ecosystems to assimilate, let alone clean.

Chapter 5 on “PPP Dream” deals with how in India water and waste is being seen as a massive business opportunity to which investment will flock once ‘the barriers’, namely government control over the resource and decisions over pricing and management are lifted and an ‘enabling policy and regulatory framework’ is created.

The report fears that in the name of inviting private sector investment, city governments are bidding for more and more expensive pieces of hardware. The private sector is lapping up this opportunity and is bringing in new systems of technology. This maybe needed in many parts of the country, but no one seems to have a clue, how these will be sustained.

Chapter 6 on “Faeconomics” spells out how all civil reckoning of the price of water and waste is incomplete without two questions: "Who gets the water and how much? And secondly, whose waste is collected, treated and disposed off into the river?"

The report spells out a six-fold strategy for managing water and waste in its last chapter “The agenda for water to water”.

First, provide clean water to all. Establish the right to sufficient water and focus on equity in supply. Legislate and ensure safe water.

Second, augment local water supply to cut the length of the pipeline. Include groundwater in the demand-supply math and make the information reliable, and public. Legislate to protect water bodies: recognize the many functions they serve, by transforming rainfall into an asset. Provide incentives for rainwater harvesting.

Third, get rich without water. Promote water-efficient appliance standards.

Fourth, redesign the flush toilet.

Fifth, invest in sewage management. Provide sanitation for all and treat the sewage of all. Make drains the treatment zones: decentralize clean-up. Connect flush toilets to rivers that actually flow.

Sixth, reuse and recycle water. Recognize and support re-use in agriculture. Assimilate the water-to-water cycle in managing supply as well as waste.

This book is easy to understand and the ideas are direct and simple. The chapter “Faeconomics” in particular extensively outlines how the costs related to water utilities are hidden under various heads and never compiled. Many of the concepts are appropriately repeated so it is hard to be lost in the discussion. The discussions are quite lengthy at places but luckily each chapter serves as good reading material independently.

The book has much to say on how bad economics has thinly disguised the actions of special interests be it the market or the state. This is a riveting book with good empirical analysis and is highly recommended for those interested in water and waste management especially water resources managers, policy makers and activists.