Guest post by: Chicu Lokgariwar, People's Science Institute Dehradun

Rhododendron forest near Dharali, in the Pindar Valley. Respondents indicated that rhododendron is flowering 15-odd days earlier than it used to a decade earlier

Rhododendron forest near Dharali, in the Pindar Valley. Respondents indicated that rhododendron is flowering 15-odd days earlier than it used to a decade earlier

Most people in the Himalayan regions are subsistence farmers with no reserve to help them tide over a poor harvest or other crisis. This in combination with a lack of access to information means that they have little or no resilience to environmental changes. Considering that climate change is a leading factor in such changes, it is necessary to help mountain communities develop their resilience to climate change induced effects. The challenge in this is that climate change manifests itself in varying forms across regions. Once the impact of climate change on a particular area is determined, a set of solutions to strengthen the environment’s and society’s vulnerability can be devised.

The Kafni glacier. Studies show that this is retreating

The Kafni glacier. Studies show that this is retreating

With this end in view, the Peoples Science institute, Dehradun supported by the Himmothan Trust conducted a baseline study of the impact of climate change in the Bhagirathi and Pindar valleys in Uttarakhand from June 2009 to May 2010. This was followed by a study on the resilience of these communities to climate change impacts in 2011. The areas studied ranged from 2000 to 3860 metres above sea level. The methods used included participatory means such as group interviews and direct collection of information through quadrat surveys. The field surveys have provided us with baseline information about species composition in the bugyals, forests and cropping patterns in the fields and orchards. Similarly, information about pastoralism, bee-keeping, and other activities was also obtained. Information about historical weather patterns and recent changes were noted.

Oak forests at Dharali are heavily harvested. Lopping without a fallow period does not allow for regeneration, and consequently a dying forest. Note the parasitical growth on all the trees, an indicator of decaying wood

Oak forests at Dharali are heavily harvested. Lopping without a fallow period does not allow for regeneration, and consequently a dying forest. Note the parasitical growth on all the trees, an indicator of decaying wood

Some of the changes observed can be directly attributed to climate change. Unpredictability in when precipitation occurs appears to be the defining characteristic of climate change in mountain areas. This makes it difficult for mountain communities to plan strategies to cope with the events they witness. There is a drastic decrease in snowfall which is leading to a decrease in the snow cover on the mountains surrounding the valley. This results in a decrease in water availability in the streams and rivers in summer. At the same time, there is a sharp decrease in winter rainfall. This is leading to a decline in the production of wheat and potatoes and consequently has an impact on food security. Similarly, this lack of rainfall increases aridity which encourages the proliferation of thrips that impact the apple crop. Lack of freezing temperatures has led to a decrease in apple production in the Bhagirathi valley.

There are several other changes that are at least partially influenced by climate change. The species composition in the bugyals in both the Bhagirathi and Pindar valleys is changing, with a greater proportion of invasives and grasses. Similarly, there is a lack of regeneration of oak, and an increase in the spread of pine forests. These cannot be solely attributed to climate change as anthropogenic factors influence these to a great extent; their impact on livelihoods is unquestionable.

One of the few still practicing this profession in Bagori in the Bhagirathi valley. Very few people of the present generation are interested becoming shepherds

One of the few still practicing this profession in Bagori in the Bhagirathi valley. Very few people of the present generation are interested becoming shepherds

The uncertainty in the weather is a strong argument for focusing on increasing the resilience of the communities and ecosystems to enable them to adapt to unpredictable change (Tompkins and Adger, 2004).The major concerns of the communities are their dependence on monoculture and on winter rainfall. Strategies to decrease their reliance on these factors will increase their resilience to climate change impact. These strategies also need to include sustaining their food security in the face of winter droughts. Establishing a system for managing commons will help prevent over-exploitation of natural resources that are already vulnerable due to climate change.

Villagers in both valleys are already attempting to reduce this dependence on a single crop by a variety of means which range from growing vegetables and diversifying income sources to include manual labour to an increasing dependence on remittances. The barley, buckwheat and millet crops associated with the hills are replaced by wheat. The tourists on whom villagers depend for livelihood demand a variety of vegetables, which is leading to their import. The elements that define mountain communities for external observers comprise their reliance on high-altitude crops, self-sufficiency, and use of high altitude natural resources. These elements no longer exist. Even as urban foods are taking over the local cuisine, the very ecosystems are changing their form, and lower-altitude flora and fauna are met with at increasingly higher altitudes.

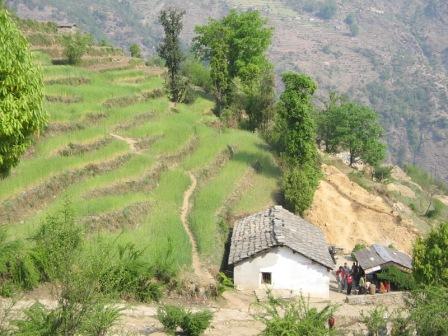

Wheat fields at Wachum, a village on the trekking route to the Pindari Glacier. The people have gathered to receive compensation for crop failure

Wheat fields at Wachum, a village on the trekking route to the Pindari Glacier. The people have gathered to receive compensation for crop failure

The strategies adopted by mountain peoples are necessary for the individuals to survive. These also have repercussions that impact the cultural dynamic of these communities by leading to an adoption of urban materials and influences. The paradox of Theseus’ ship is apt here. If every plank on a famous ship is changed over the years, can it still be said to be preserved? If the elements that till today have defined mountain communities are to disappear while the population continues to live in the area, can these mountain agrarian communities be said to survive, or to have become extinct? It needs to be accepted that adapting to climate change needs creative effort. Sadly, an acceptance of the need to let go of the practices that defined a community if the individuals in that community are to survive is just as necessary.

Acknowledgement:

This article was written based on information gathered during a study of the impact of climate change on mountain communities in Uttarakhand conducted with the financial support of Himmothhan (India) in 2009 and a study on resilience carried out with financial assistance from the Ecocultures Research Programme at the University of Essex (For enquiries contact Zareen Bharucha at zpbhar@essex.ac.uk).