Water, sanitation and hygiene, which are major determinants of health and nutrition levels, have gained substantial visibility during the last two years because of the pandemic. It has been well established that safe drinking water, quality sanitation, and good hygiene contribute to the prevention of disease and promotion of health. Thereby, all three have long-term beneficial economic implications.

In India, 38.4 per cent of children under the age of five years are stunted, and half of all undernutrition cases are associated with diarrhoea and 30 infections result from unsafe water, poor sanitation, and unhygienic behaviour[i].

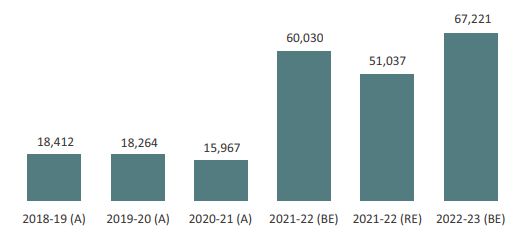

This year's budget has continued to give priority to the provisioning of drinking water. In the Budget Estimate (BE) for 2022-23, the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, under the Ministry of Jal Shakti, has been given a 12 per cent increase in allocation over the 2021-22 (BE) (Refer to Figure below).

Figure: Budgetary allocation/expenditure for the Department of Drinking Water & Sanitation (Rs. crore)

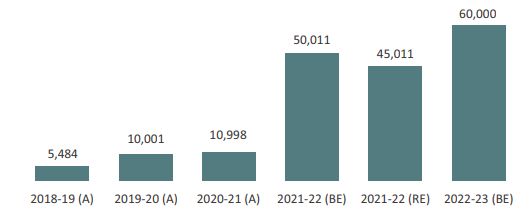

The main reason for this has been the (19.9 per cent) rise in allocation for the government's flagship Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) scheme in 2022-23 (BE) against the allocation made last year (Refer to Figure below). This allocation of Rs 60,000 crore confirms the significance of the water supply in the second year of the pandemic. However, a point of concern has been the decrease in the Revised Estimate (Rs 45,011 crore) in 2021-22 in comparison to BE 2021-22. This could stem from the fact that the implementation of work under the scheme may have been stalled due to the pandemic.

Figure: Union Government's Expenditure / Allocation for Jal Jeevan Mission/NRDWP (Rs crore)

The JJM, which has completed more than two years, has picked up pace in terms of coverage, with about 5.5 crore households or 29 per cent of target beneficiaries, being provided with piped water supply as of 1st January, 2022.

However, the coverage of the scheme has seen wide variations across states. While six states/UTs (Goa, Telangana, A&N Islands, Puducherry, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu and Haryana) have provided piped water supply to 100 per cent of households, several states, including Jharkhand, Bihar, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh, have covered less than 10 per cent of rural households under the scheme[ii]. Further, until 19th January 2022, about 8.3 lakh government schools had been provided with 32 piped water facilities under the JJM[iii].

Despite increasing allocations for the scheme, the previous year's utilisation reflects a bleak picture, with only 26 per cent of the allocated amount released ll January 2022, with varying fund utilisation levels by states[iv]. While 13 states, including West Bengal, Jharkhand, and Tamil Nadu, have utilised less than half of their available funds, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana had spent more than 70 per cent of their funds up to 1st January, 2022.

In addition, a large amount of unspent balances, to the tune of Rs 2,436.4 crore and Rs 6,431.9 crore, were 35 already lying with states in FY 2018-19 and FY 2019-20, respectively. This implies that there is a need to identify administrative and procedural bottlenecks in the effective absorption of resources for the sector, especially when the budgetary provision has been stepped up significantly.

The National Water Quality Sub-Mission was launched with a view to provide safe drinking water to fluoride and arsenic affected rural habitations. States are free to spend 10 per cent of the total allocated funds under JJM on habitations with water quality issues. However, not all states have spent enough on the water quality sub component[v].

In 2021-22, except for Punjab, which has spent 100 per cent of funds available for water quality, many states, including Maharashtra, Telangana, Kerala and Himachal Pradesh, have spent no funds on the water quality component. It should also be noted that up to two per cent of the funds allocated under JJM are earmarked for strengthening of the water quality monitoring infrastructure. However, the Standing Committee on Water Resources (2021-22) pointed out that the decreasing number of water testing laboratories is a cause of concern[vi].

Budgetary priority for sanitation sees a decline

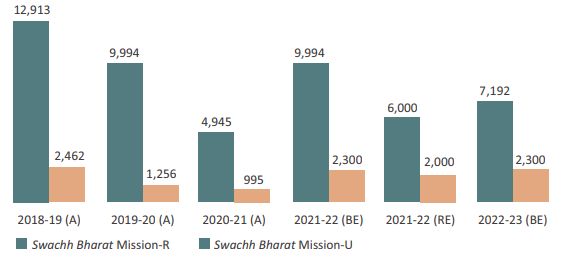

In the case of sanitation, the 2022-23 (BE) allocation for the Swachh Bharat Mission – Rural (SBM-R) has registered a decline of 28 per cent in comparison with 2021-22 BE (Refer to Figure below). The allocation for SBM Urban in 2022-23 (BE) has not registered any change and remained constant compared to 2021-22 BE (Refer to Figure below). Given the rapid growth of urbanisation in the country, a greater allocation for SBM(U) was expected.

Figure: Union Government's Budgetary Expenditure/Allocation for Swachh Bharat Mission (Rural & Urban) (Rs crore)

Under the Swachh Bharat Mission - Phase II[vii], 7.16 lakh individual household latrines were constructed for households and 19,061 Community Sanitary Complexes were constructed in 2021-22. Recently released data from the National Family Health Survey - 5, also shows that rural households with improved sanitation facilities registered an impressive increase from 48.5 per cent in 2015-16 to 70 per cent in 2019-21[viii].

This increase, however, has not been uniform across states. Many states continue to have sanitation coverage below the national average of 70 per cent. These include Bihar (49 per cent), Jharkhand (57 per cent), Odisha (60 per cent), Manipur (65 per cent), Madhya Pradesh (65 per cent), West Bengal (68 per cent), Assam (69 per cent) and Uttar Pradesh (69 per cent). This indicates that less developed states have continued to lag behind in the provision of sanitation services, despite the overall success of the scheme.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the SBM, JJM and Samagra Shiksha schemes have contributed significantly to the provision of drinking water, toilets and hand-washing facilities in 10.32 lakh government schools. According to UDISE, coverage of boy's toilets in government schools increased from 67.8 per cent in 2012-13 to 95.9 per cent in 2019-20. Similarly, the provision of handwash facilities in government schools increased from 36.3 per cent in 2012-13 to 90.2 per cent in 2019-20.

Need for a renewed focus on SBM and hand hygiene

In order to not lose the gains made by SBM, it is necessary not only to refocus and increase budgetary allocations towards Phase II of the Mission but also to pay attention to the need for hand hygiene. COVID-19, despite being a public health emergency, is also a WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) emergency. One of the most effective preventive measures against COVID-19 is following COVID-appropriate protocols. These include handwashing with soap and water at critical times; masking, and maintaining an appropriate physical distance.

Hence, hygiene gains prominence not only in the current discourse of the WASH pedagogy but also as a preventive and protective measure for future epidemics. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for Water supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Report - 2021 shows that 68 per cent of the population in India has basic hygiene services, 29 per cent has limited hygiene services and 3 per cent has no facility for hygiene services[ix].

Despite the global pressure on hygiene promotion and even prior to the pandemic, India's hygiene data painted a gloomy picture. The National Sample Survey - 76th Round (2018-19) revealed that 64.2 per cent of household members (44 per cent urban, 74.7 per cent rural) did not wash their hands before eating, while 25.9 per cent (11.7 per cent urban, 33.2 per cent rural) did not wash their hands with soap after defecation.

Further, even in institutions such as schools and anganwadi centres, the situation was dismal[x]. Budgets for sanitation and hand hygiene should therefore be stepped up for households and institutions.

The full report by CBGA 'In search of inclusive recovery: An analysis of Union Budget 2022-23' can be accessed here

References

[i] Townsend J., Greenland K., & Curs V. (2016). Costs of diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection attributable to not handwashing: the cases of India and China. Tropical Medicine & Internal Health. 22(1), 74-81. hps://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12808.

[ii] Economic Survey, 2021-22, Government of India

[iii] Economic Survey, 2021-22, Government of India

[iv] Standing Committee on Water Resources (2021-22), 14th Report, 2021-22, 17th Lok Sabha, Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Jal Shakti, GoI

[v] Jal Jeevan Mission IMIS system, Financial Progress, Format D1 - State wise Allocation, Release and Expenditure

[vi] Standing Committee on Water Resources (2021-22), 14th Report, 17th Lok Sabha, Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Jal Shakti, GoI es (2021-22), 14th Report, 2021-22, 17th Lok Sabha, Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Jal Shak, GoI

[vii] SBM-Phase II focuses on ODF sustainability and waste management

[viii] National Family Health Survey (2019-21), Round 5

[ix] Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: five years into the SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) 2021

[x] Promises & Reality: Citizen's Report on Year Two of the NDA II Government, 2020-2021, Wada Na Todo Abhiyan