A recent news report said that UNICEF was promoting a machine that purifies sweat from people’s clothes to get potable drinking water (Fox News). Sounds gross? Yes, as much as this may not be to everyone’s taste, the idea was to bring out an important message - clean and safe drinking water isn't available as freely as we think.

Lack of safe drinking water kills more people worldwide than war does. “Patients suffering from water-related diseases occupy half of the world’s hospital beds. Water-borne diseases like typhoid, or hepatitis, kill a child every fifteen seconds” (1). As per a news report “the Indian economy loses 73 million working days a year due to waterborne diseases, caused by a combination of lack of clean water and inadequate sanitation” (3). In India, lower income groups in particular, do not have consistent access to safe drinking water.

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs - a United Nations effort to build a better world) to which India is a signatory, says that the country should halve the proportion of people without safe water access from base period 1990 to 2015. While we seem to be on track as far as MDGs are concerned, this point is open to discussion as improved water access through various sources may not necessarily translate into safe water availability for all. We may be overestimating the proportion of households with access to safe drinking water.

One possible solution to meet this crisis is technology, especially cheap and effective water purification technology.

Unlocking the potential of blue technologies

The demand for household-level water purification systems in both urban and rural India is on the rise these days. This includes not only treating water to remove biological contaminants but also pollutants like heavy metals and geogenic contaminants like arsenic and fluoride, which are naturally found in water. A number of low-cost blue technologies that can provide safe treated water to low-income households are already in the market while some are still being developed.

"Targeted investments in communities and individuals, along with institutions, will allow India to expand and ensure safe access to water and sanitation to all its residents well beyond 2015”, according to Sridhar Vedachalam, a researcher (4). A compelling business model that lets companies commercialize these technologies for target consumers is a matter of concern though. The Indus Entrepreneurs (TiE), a group that fosters entrepreneurship globally through mentoring, networking, and education, along with the Institute for Rural Research and Development (IRRAD), a Gurgaon based NGO had organized a seminar to discuss this topic recently .

The seminar generated discussions through which entrepreneurs, development practitioners, policymakers and academics shared their knowledge and best practices on successful commercialization of blue technologies. They showcased successful scale-up models and the sequence of commercialization and enterprise scale-up. Several market players and civil society groups working in this field presented their experiences as well.

Tata Chemicals, which has been building and maintaining access to rural markets through innovations, felt that the solutions demanded by people are aspirational and hi-tech. A Base of Pyramid (BoP) customer i.e., one who is at the bottom of the income pyramid is as demanding as anyone else, said Amrita Dey. The company’s experience with marketing Tata Swach, the low cost water purifier suggests that acquiring customers is more difficult in rural than in urban areas. “Till recently, rural Indian markets were not exposed to water purifiers as a result of economic factors and poor sales and distribution networks in these areas” (5). What's more, rural projects generally have a high gestation period. The partnerships in rural areas should therefore be developed as a self-sustaining channel that builds on already existing systems, said Dey. Furthermore, the channel should not be solely dependent on one product. Inadequate infrastructure and lack of granular or specific information on local markets pose a problem in sales and distribution scale-up.

The advent of nanotechnology

Nanotechnologies are an answer to improving access to safe drinking water, according to Development Alternatives, a Delhi based NGO working on water and allied issues. This technology, which deals with the special properties of matter that occurs below a given size threshold, has been applied in the field of water purification.

The product developed by Development Alternatives - Aqua+ - contains Sodium Hypochlorite solution, which acts as a disinfectant. Also known as liquid chlorine, a 50 ml bottle of Aqua + can treat 500 litres of water. The product is very easy to use and per Siddhartha Bountra, Manager, Water Product & Services, Development Alternatives has already sold 100,000 bottles as a pilot to establish product acceptability.

Nanotechnology research in India has grown at a very fast rate, especially in the water and energy sectors, said Kriti Nagrath of Development Alternatives. Research is looking at low-cost material and manufacturing options to cater to the needs of the developing world. A range of water treatment devices that incorporate nanotechnology are already in the market.

So the market does exist and the power of the enterprise will take service delivery to scale. The challenge is to make the initiative self-sustaining by scaling up operations. Bountra estimated that the 167 million families in Indian BoP translate into a demand of 20 million bottles per year or Rs. 600 million in revenue per year.

Barriers to nanotechnology in India

There are two big barriers to the introduction of nanotechnology in India.

- Environmental impact

Its effect on our health as well as the environmental impact of the technology is the biggest concern; it isn't clear how used filters and media containing nanomaterials might affect the environment. “Because nanoparticles are very different from their everyday counterparts, their adverse effects cannot be derived from the known toxicity of the macro-sized material. This poses significant issues for addressing the health and environmental impact of free nanoparticles.”(6)

What if they emerge as a completely new class of non-biodegradable pollutant tomorrow?

- Policy gap

Bountara feels that there is disconnect between researchers and the industry when it comes to nanotechnology. There is policy gap in terms of monitoring, production and application of nanotechnology-based devices. The disclosure on nanomaterial used is vague. There is no standardized protocol for evaluating environmental impact. The market might be ready for this technology but more industries and start-ups need to be attracted and get involved.

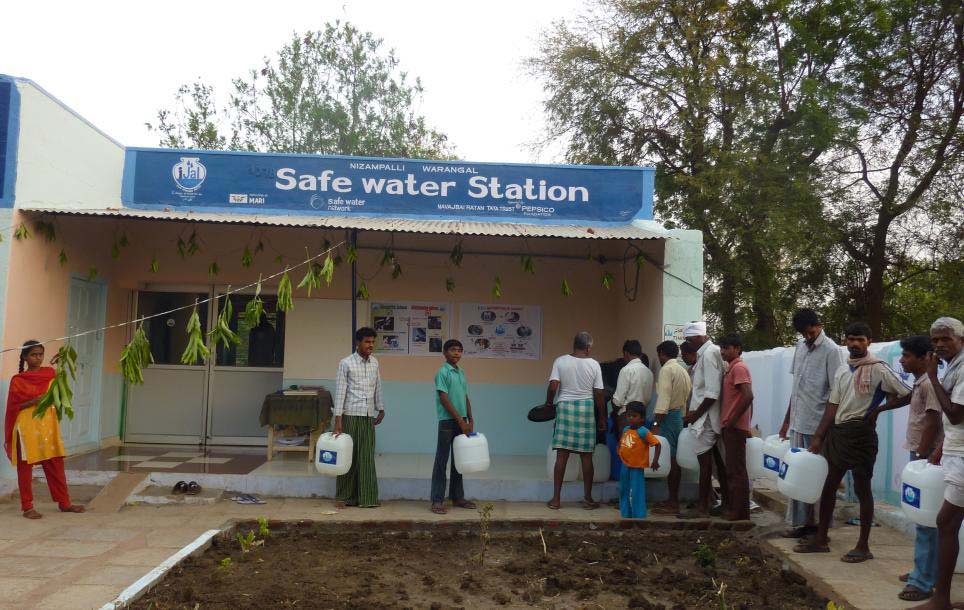

Safe Water Network talked about how they were promoting decentralized village-level safe water stations and also rainwater harvesting. The Network works on developing locally owned and managed water systems to achieve lasting health impact. They addressed the problem of excess fluoride, total dissolved solids and microbial contaminants in local groundwater. They also promoted locally owned market-based models that provide access to safe water. These cost-effective and flexible systems can be operated in a variety of challenging conditions. The barriers to system sustainability are taken care of by ensuring that each station is locally owned, said Ms Poonam Sewak, Institutional Development Manager, Safe Water Network.

The network has created an innovative financing program to enable low-income, rural populations to install cisterns at the household level. Diverse business models were suggested in decentralized water systems. The most promising was one where a part of the capital cost to set up the plant was provided by a private donor or collectively by the community. Institutional lenders could provide the remaining funds. This loan could be paid off by the community over time. The community could pay off the running costs for plant operations.

In conclusion, we still have a long way to go to make these systems commercially viable and scale them up for the benefit of a community but the landscape for water treatment solutions looks promising and 'blue'.

References

(1) https://www.wateraid.org/~/media/Publications/human-waste.pdf

(2) https://www.unicef.org/media/files/JMPreport2012.pdf

(3) Gupta, S. (2012), ‘Woman who risked marriage for sanitation awarded’, The Times of India, February 24, available at: http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-02-24/bhopal/31094479_1_toilet-tribal-woman-sulabh-international)

(4) Water supply and sanitation in India: Meeting targets and beyond (pdf), Cornell University).