In India, there has been a stunning growth of inequality in the last 25 years and a spectacular growth of inequality in the last 15 years. It is not just a question of wealth and income; inequality is visible in every sector. It is visible in water whether (it is) water for irrigation or drinking water. Transfers of water from poor to rich, from agriculture to industry, from village to city are going on.

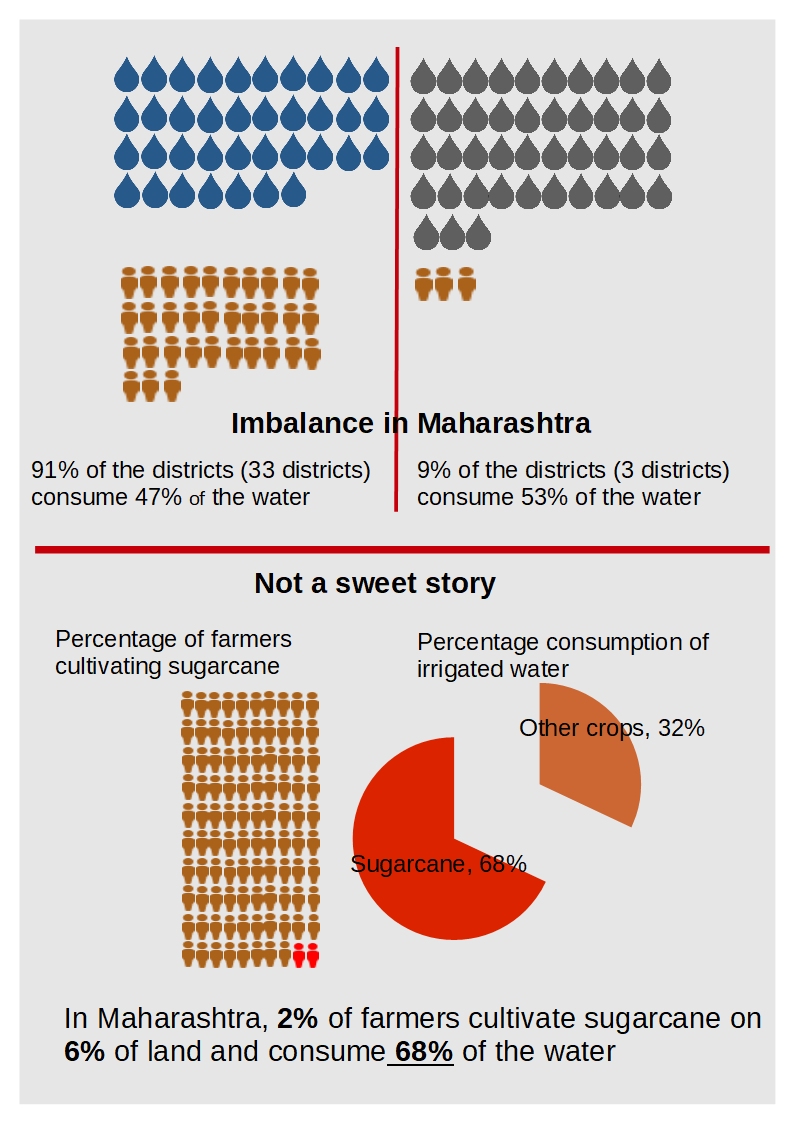

The Times of India correspondent, Priyanka Kakotkar analysed water distribution in Maharashtra with the help of an RTI application. Urban Maharashtra gets 400 percent more than village Maharashtra. Fifty-three percent of Maharashtra’s water is  consumed in three out of 36 districts--Mumbai, Nashik and Pune. All this water is being sucked from the villages where the lakes are. All of Mumbai’s water comes from five lakes in Thane. In Thane district, 75 years after independence, you will not find a single Adivasi house with piped water connection. Are people in the villages less thirsty?

consumed in three out of 36 districts--Mumbai, Nashik and Pune. All this water is being sucked from the villages where the lakes are. All of Mumbai’s water comes from five lakes in Thane. In Thane district, 75 years after independence, you will not find a single Adivasi house with piped water connection. Are people in the villages less thirsty?

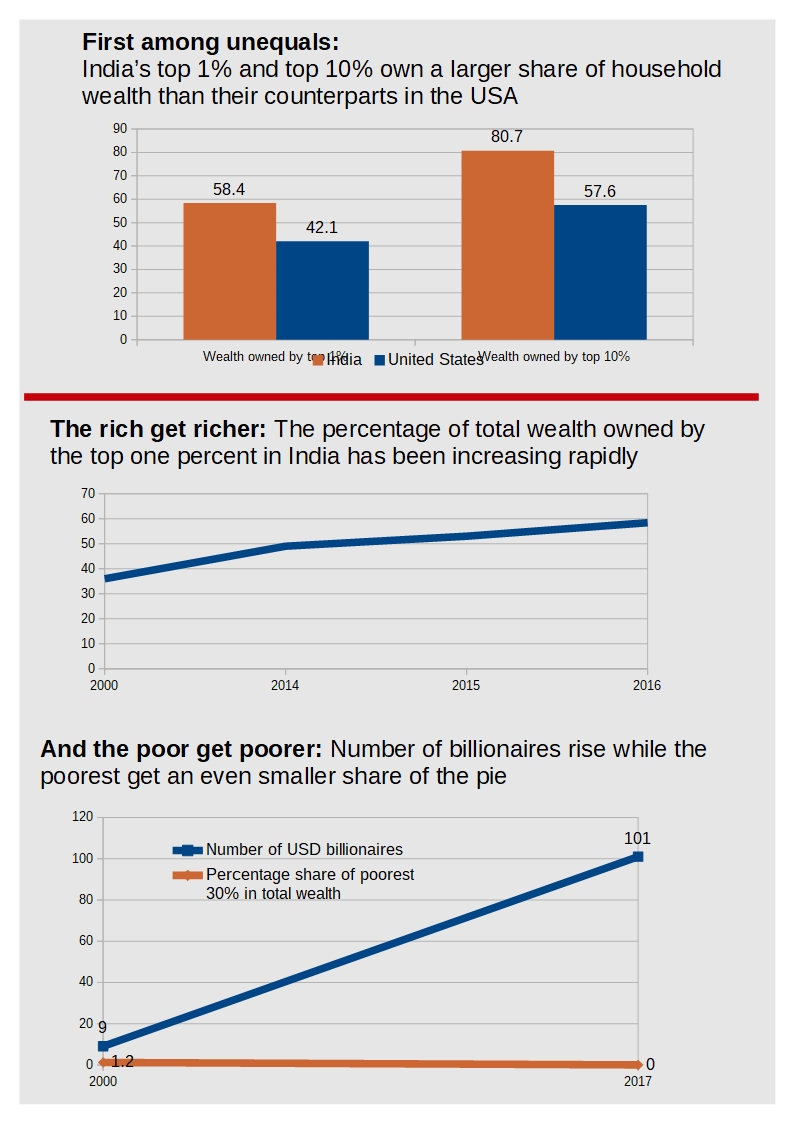

Every year since 2014, Credit Suisse brings out the Global Wealth Data Book which contains tables giving information about 130 nations. In India, the top one percent owns 58.4 percent of the total household wealth. If you were to look at the United States, the control of the top one percent is just 42.1 percent. The control of the top 10 percent is 80.7 percent in India; in the United States, it is 57.6 percent. Your inequality is more than that of the quintessential neoliberal capitalist economy of today.

Look at the bottom 30 percent in India. The share of the bottom 10 percent is -0.7 (percent). This means serious debt. India’s poorest are drowning in debt. The next decile, 20 percent, has 0.2 percent; the third decile, 30 percent, has 0.5 percent. This means that the ownership of the bottom 30 percent is zero; they own nothing. Look further at the bottom 90 percent--they own 19.8 percent of total household wealth. That means, the top one percent owns three times what 90 percent of the population does. That is an incredible, intolerable, level of inequality.

In 2015, the Indian top one percent owned 53.0 percent. In 2014, the share of the top one percent was 49 percent. In 24 months, the one percent sitting at the top added 10 percentage points to their wealth. In 2000, this share was 36 percent. You will not find this rate of accumulation in any other country. You are living through the greatest loot and grab sortie in your history.

This is because the main characteristics of the inequality we have in India is that it is driven by policy. This is not the inequality of any natural calamity; this is a planned inequality, a constructed inequality. It is most cynically constructed and most consciously engineered. What is the difference between the inequality of 30 years ago and the inequality of today? Thirty years ago, you planned for equality. Now you plan for inequality.

In 2000, India had nine dollar billionaires; in 2009, there were 53 dollar billionaires. In 2017, the Forbes billionaire list had 101 people from India. From nine to 101--a phenomenal growth of billionaires. But look at the bottom one percent. From +0.1 percent they went to -0.7 percent. The 20 percent went from 0.4 to 0.2 and the third decile went from 0.7 to 0.5. So you cannot say the cake is getting bigger and everyone is getting more. That is not the case. Wealth is being sucked upwards. And it is being sucked upwards by engineered and constructed policy.

This inequality is being reflected in lifestyles and can be illustrated by developments in architecture. Maharashtra has the century’s greatest drought. That has not stopped the kind of building constructions that are coming up in Maharashtra with a swimming pool on every single floor. Buildings like these are not confined to Mumbai, they are coming up everywhere. They are also coming up in Baramati, Sharad Pawar’s constituency, a rural area. I interviewed the labourers working on the site and asked them who they were.

‘Sir, we are farmers. We are farm labourers.’

“What are you doing here? Why are you not in the villages? Don’t you want to farm?”

“What farming can I do, sir? Where is the water?”

Where is water in the villages? So our fields are lying fallow. I cannot tell you what it felt like for me that they have abandoned their fields because there is no water in the village and come to build your swimming pool and mine in the city. For me this is intolerable; it is just intolerable. We are building for a huge, gigantic explosion. You cannot have such inequalities.

Just two or five kilometers from there, you should see how the ordinary citizen lives. This is how the average Indian woman gets her water. The woman who keeps a pot in the queue for this tap, has also kept six other buckets near six other public taps. This is the Indian woman’s water gathering task and ordeal. But no matter where you have placed your bucket in a queue, it does not work if you are a Dalit. If you are a Dalit, I will simply kick your bucket away. I spoke to a Dalit woman in such a queue. She said, “Sir, this is the sixth time I have sat here. I have placed a bucket at each tap, and I have placed it first at around three in the morning. But I always get water last.”

In India, there is a caste and class geography in irrigation and in domestic water. In Marathwada, from January to April, in each household, one person spends one entire day every week just collecting water. And this same Marathwada is home to our billionaires who are the people in the sugar lobby. Look at the inequalities in control of water in Maharashtra. The two percent of farmers who are sugarcane cultivators utilise 68 percent of irrigation water cultivating six percent of land. These same people have now also joined industry, and diversions are happening. There were firings in which five to six farmers died protesting against the transfer of water from Maval to Pimpri-Chinchvad.

In India, there is a caste and class geography in irrigation and in domestic water. In Marathwada, from January to April, in each household, one person spends one entire day every week just collecting water. And this same Marathwada is home to our billionaires who are the people in the sugar lobby. Look at the inequalities in control of water in Maharashtra. The two percent of farmers who are sugarcane cultivators utilise 68 percent of irrigation water cultivating six percent of land. These same people have now also joined industry, and diversions are happening. There were firings in which five to six farmers died protesting against the transfer of water from Maval to Pimpri-Chinchvad.

So you have the inequality of wealth and the inequality of water. The inequality of income is equally startling. Paul Krugman, in his 2002 essay The Gilded Age, said, “When the wage difference between the top CEO of a company and the lowest worker in a factory crosses a 100, you have a crisis of inequality; when it crosses 1000, you have a crisis of democracy.” Take the top Reliance CEO’s salary and that of the lowest contracted worker, the difference is not 100, it is not 1000, it is 30,000 to 40,000. In 2015, a young economist with ThoughtWorks software consultancy in Gurgaon, Srujana Brodapati calculated that 15 Indian individuals owned more wealth than the bottom 50 percent.

The biggest sector where rising inequalities show terribly is in agriculture, where 15 million farmers have quit agriculture between 1991 and 2011. Where have they gone? The same primary census abstract that shows the decline in farmers has the answer. Next to the column of farmers is the column of agricultural labourers. As the number of farmers is decreasing, the number of farm workers is increasing. In united Andhra Pradesh, the population of farmers has decreased by 13 lakhs in a decade, from 2001 to 2011. The number of labourers has increased by 34 lakhs. This means that it is not just farmers’ livelihoods that are collapsing, but also many others. So you are having an incredible rise in inequalities in all forms.

When you are looking at wealth, what is the income and ownership and wealth of the average rural Indian? According to the socio economic caste census done in 2013-14, in 75 percent of rural India, the main breadwinner earns less than Rs 5,000; in 90 percent of the households, the main breadwinner takes home less than Rs 10,000. But you have 101 dollar billionaires.

And now to the farmers. A situation assessment report of the National Sample Survey came out in 2014, with 2013 data presenting information about farm households. The average farm household in India, considering all sources of income, has a monthly average income of Rs 6,426. Punjab, Kerala, Haryana are on one side of the spectrum where the income is from Rs 10,000-12,000. East UP and Chattisgarh are on the other, where the income is as low as Rs 3,000. The levels of inequality are driven by the credit policies of the government of India.

Successive governments say they have doubled agricultural credit. That credit does not go to agriculturists; it goes to corporate agribusiness. Fifty-three percent of the total agricultural outlay by NABARD goes to Mumbai and suburbs. How many small farmers are there in Mumbai? A professor at TISS, Rama Kumar has analysed the changes in agricultural credit. According to him, the loans from Rs 10 crore to Rs 25 crore have doubled. The loans below Rs 50,000 have collapsed. How many of you have met farmers who take loans of Rs 20 crores? Agricultural crisis is a manmade crisis, we are very deeply in it.

The National Crime Record Bureau is a division of the home ministry. According to them, from 1995 to 2015, more than 3,10,000 farmers have committed suicide in this country. Two thirds of those happened in six states--Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Chattisgarh and Telangana. And what is the response of the government? They have shut down the NCRB. They have shut down the division that processes the data.

You are in a situation of unsustainable inequality. It will not show in nice ways such as organised struggles. But it will show in rising fundamentalism, in rising obscurantism. It’s going to show in rising criminalisation of dissent.

I want to leave you with this line: Don’t see the economics as separate from the social.

Bibek Dubroy, one of the advisors of the Prime Minister’s economic council debated Thomas Piketty (French economist whose work focuses on wealth and income inequality) and said that inequality is not an issue. The chief economic advisor, Arvind Subramaniam was also present at that interview. Bibek Dubroy said, “If someone makes a lot of money, what is wrong with them flaunting it? It’s not our business.” Arvind Subramaniam said, “I have to go with Bibek on this one.” Even in the mid-90s, had the chief economic advisor of the government of India said inequality is not an issue, he would be looking for a job next week. Now we are making a virtue of this.

I ask you, where is our anger? I would say that either we fight back against inequality or we look at what Ambedkar said in that fantastic speech on November 25, 1949. He said, “I am handing over this fine document (Indian Constitution) to you in some trepidation. We have entered the world of paradoxes. In politics, there is democracy; in society and economics, there is no democracy at all. In politics, there is democracy and equality; in society and economics, there is no equality. And one day, the tension between those dispossessed of democracy and equality and your political system fine political will explode your fine political democracy.”

That is our choice.

P. Sainath, recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay award in 2007, is a journalist who has focused on rural affairs and inequality in India for the last 30 years. He is author of the book “Everybody loves a Good Drought’ which remains a definitive work on famine and hunger in India.

This article is excerpted from a speech made by him for the 15th Rahul Sankrutayan Memorial Lecture organised by PAHAR in Nainital. Download the full transcript below.