At a workshop on Water Ethics leading up to the Water Future Conference in Bangalore in September 2019, the idea of, and the need for an ethical framework for water management and legislation was discussed. In a country as diverse and complex as India, ethics play an important role in how we view water, and thus manage it. Ensuring equity in access to safe water to all is a huge task – but we must be guided by some basic ethics when endeavouring to achieve this.

David Groenfeldt of the Water-Culture Institute kicked off the workshop at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) on a rainy Monday morning in Bangalore, starting with why we should be concerned about water ethics and values. It’s important first of all, to distinguish between ethics and values because both words are often used interchangeably.

Ethics integrate values; ethics influence how we act or how we feel we should act, and are guided by the values we hold dear. Ethics help us make sense of our values. It has judgement built into it – “we should be doing things this way because it isn’t working the way it is”.

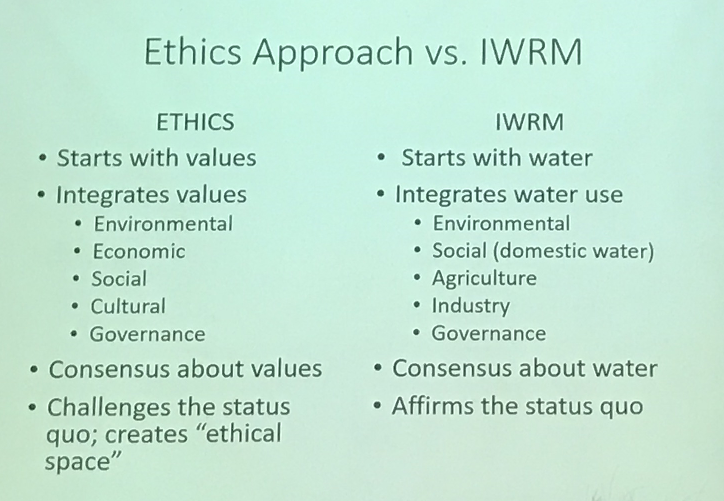

David went on to rightly point out that the very word ethics, is rarely used in water legislation or regulatory frameworks, but every law and policy is inherently based on an ethical framework. He went on to highlight the differences between an ethics approach and an Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) approach.

Modern perceptions around water value it as a resource – something that can be tapped, used, consumed, and of course, something that needs to be protected, conserved and managed sustainably. Traditionally, water was valued almost like a relative – an entity that was cared about, almost a living entity that was revered.

The myriad values of water and water ecosystems

IWRM recognizes multiple values of water and water ecosystems. Below are what these values mean in the context of water (in no particular order):

- The economic value of water pertains to a cost-benefit analysis of water, looking at efficient use of water, and avoiding wastage of real and virtual water.

- The environmental value of water relates to mitigating the negative impacts of climate change, water scarcity and changing landscapes in which water exists. The environmental value of water prioritises the health of water ecosystems.

- The social value of water looks at justice and equity, focussing on human health and well being including the fundamental right to water and sanitation.

- The cultural and spiritual values of water relate to identity, meaning and the relationship between communities and water.

- The governance value of water look at transparency, accountability and participation from all stakeholders.

Weighing the importance and impacts of identifying synergies and trade offs between differing values, is facilitated by an ethical analysis and framework. Can there be synergies between a healthy environment and a healthy economy, for instance? Can there be a balance between environmental and economic values? Synergies and trade offs become particularly important in the context of the question around equity in access to water, and the cost of water for the rich and the poor.

The prevailing theoretical construct around water, particularly in the water sector in India, is that water is a common pool resource, or a commons. This is essentially rooted in a value system, and is also a fact – that water is an intergenerational and geographic commons, and needs to be managed as such.

Rivers have social, environmental and economic purposes, not just in India but across the world. Rivers are often a cultural identity for indigenous communities, and have been revered for centuries – from the Cauvery in the south to the Ganges in the north. Yet, rivers and water bodies that are religiously symbolic and significant, are often at the receiving end of pollution – from cremating the dead to raw untreated sewage and plastic idols.

This anomaly between reverence for, and ill treatment of, the very same resource – a water body – continues unabated.

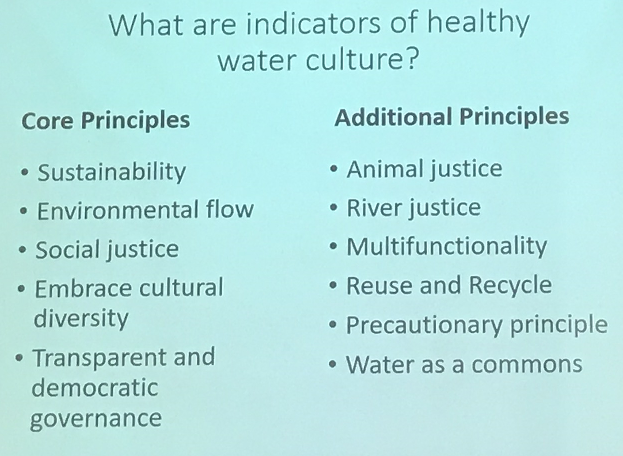

Our collective values around water, as a society, need to be redefined within a framework for how we think about and perceive water and its management. The ecosystem of water values constitutes a distinctive water culture that is dynamic and constantly changing.

There has been much debate around the use of dams across the world. In the US, some dams are being removed as they have reached the ends of their lives – but it is important and interesting to note that it is almost as expensive to remove a dam as it is to build one. Here, the economic, social and environmental values regarding large dams are at odds with one another in more ways than one. Water infrastructure represents “good” and “bad” values through different lenses. It is critical to recognise the subjectivity of these aspects, in designing ways to manage water.

Water ethics is an emerging field, not nearly as established as business ethics or medical ethics. It can be operationalized in various contexts. Broadly, the contours of operationalizing water ethics entail the following:

- Identify and “map” water value principles according to the 5 values (detailed above)

- Reach a working consensus about the values

- Document the values / principles into charter

- Apply the principles to water decisions

- Monitor compliance

- Resolve value conflicts

The workshop then looked at four case studies, where participants tried to apply water ethics to each case answering some key questions. What are the value conflicts? What are the corresponding ethical issues? How might an ethics perspective contribute to resolving the conflicts? What stands in the way of consensus? What opportunities do you see for finding common ground?

Learn more about water ethics here.

This article was written based on a workshop held at the Divecha Centre for Climate Change at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore on the 23rd of September 2019, jointly conducted by the Forum for Policy Dialogue on Water Conflicts in India (Pune), the Water Culture Institute (New Mexico) and Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE) (Bengaluru). The workshop was a precursor to the Water Future Conference – Towards a Sustainable Water Future in Bangalore from the 24th to the 27th of September 2019.