As part of its efforts to promote rural sanitation, the government, under the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), promises a subsidy of Rs 12,000 for the construction of individual household toilets. Households that fall in the below poverty line (BPL) category and select households such as those belonging to SCs/STs and the ones headed by women can avail of this subsidy amount.

Here’s how it works. Any person interested in constructing a household latrine approaches the gram panchayat (GP) office and submits an application for availing the subsidy. The person can either choose to construct the toilet on his own or request the GP to construct it for him. Either ways, once the application is verified, the GP forwards it to the block or district office for final sanction. Whether constructed by the individual or the GP, the subsidy amount is released in two phases--half the amount is released mid-construction, while the rest is transferred once the construction is completed and the toilet passes the district officials' mandatory inspection.

While the procedure may seem fairly straight-forward, inherent village and local bureaucracy dynamics modify the agenda a great deal. Applications remain at the GP office longer than necessary, while officials at the zilla parishad have no clear idea about the actual toilet demand at the GP or the block level. This lack of transparency, coupled with the paucity of ways to scrutinise progress made at each stage often result in projects slipping quietly into limbo.

While the procedure may seem fairly straight-forward, inherent village and local bureaucracy dynamics modify the agenda a great deal. Applications remain at the GP office longer than necessary, while officials at the zilla parishad have no clear idea about the actual toilet demand at the GP or the block level. This lack of transparency, coupled with the paucity of ways to scrutinise progress made at each stage often result in projects slipping quietly into limbo.

Keeping track of schemes

While the government, through the department of electronics and information technology’s Mobile Seva initiative, brought out a bunch of mobile applications and widgets to keep track of its services and schemes, there aren't many to monitor the progress of the programmes.

Almost a year ago, the government came out with a Swacch Bharat app which enabled citizens to upload photos of toilets and geo-tag them along with latitude and longitude details. Apart from construction, usage was to be monitored as well. Though the government's interest in incorporating information and communication technology (ICT) in tracking development was heartening, the application did little to track progress and capture demand prior to construction.

Capturing toilet needs

Samarthan, a non-profit organisation working to improve the water and sanitation services in the states of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, believes in piloting concepts and developing systems which influence policy. Their concepts have been replicated by the states. "We have always believed in working with the government and helping in reducing the ground-to-policy disconnect which centralised governance suffers from. Block and zilla level officials have to work with several constraints and it is here that we, as an NGO, step in to help out. The idea is to demonstrate simple mechanisms and assist officials in making implementation easier," says Mankaj Kumar Singh, programme director, WASH, livelihoods, urban governance at Samarthan.

Many of these previous pilots have been scaled up and adopted by the district administration including the institutionalised operation and maintenance of school toilets or establishing revolving funds at the disposal of self-help groups (SHGs) to repair and alter defunct toilets. These are not areas, covered by the SBM funds. Samarthan has also been experimenting with paying community motivators, similar to the SBM's swachhta doots or cleanliness messengers, to talk about good sanitation practices and encourage community members to make their villages open defecation free.

Many of these previous pilots have been scaled up and adopted by the district administration including the institutionalised operation and maintenance of school toilets or establishing revolving funds at the disposal of self-help groups (SHGs) to repair and alter defunct toilets. These are not areas, covered by the SBM funds. Samarthan has also been experimenting with paying community motivators, similar to the SBM's swachhta doots or cleanliness messengers, to talk about good sanitation practices and encourage community members to make their villages open defecation free.

It is with such a hope that Samarthan decided to put in place a technology pilot to identify bottlenecks in the building of toilets and come up with a solution to accurately record the actual demand for them. The idea was to first pilot, test and demonstrate a concept which could later be adopted by the district administration to streamline the process. For this, Samarthan teamed up with Dhwani Rural Information Systems to design a mobile application--mDemand--that captured the demand for toilets at the village level and the subsequent headway made in toilet construction and usage; all the way from the village to the district.

But, the challenges were many. "We had to approach the problem from a variety of angles to address technology, user-level and field-level challenges. Was this pilot only for the sake of technology or would there be any real utility? Is the entire exercise cost-efficient and capable of replication?," adds Mankaj. Eight panchayats in Sehore district were selected to test the app and study all components, from demand creation and construction to the possibility of integrating the collected data with the government's existing management information system (MIS).

Enter, mDemand!

Armed with their mobile phones, a team from Samarthan travelled from village to village to capture demand data during the pilot stage that lasted a month. The collected data was geo-referenced and photographs of aspiring toilet owners and their premises were uploaded, further strengthening the authenticity of the data.

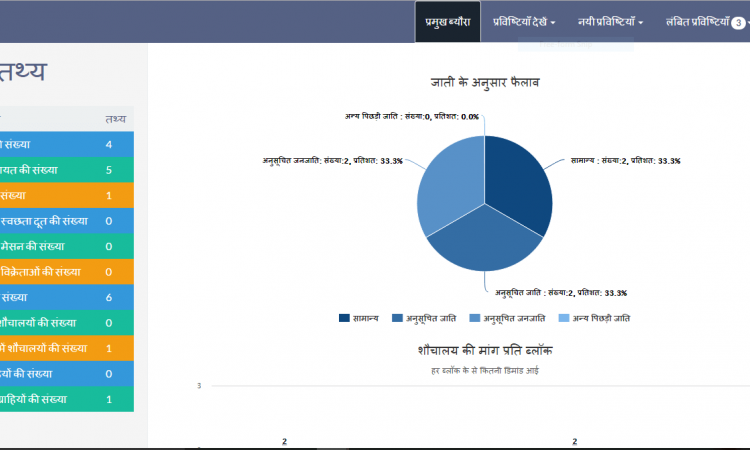

The data remains visible on the app's dashboard, which could be accessed by officials, both at the panchayat and zilla parishad levels. Thus, the journey of a toilet requisition application from an individual household could now be traced, giving an opportunity for officials to locate and fix snags throughout the course.

"Once the toilet demand data is recorded at the village level and an application has been forwarded to the GP office, its status can be tracked by implementing agencies on a real-time basis. District officials are kept informed of the overall demand at the individual village and GP levels, so that they can apportion finances accordingly," explains co-founder of Dhwani, Sunandan Madan.

Won't excel sheets suffice? The app, Sunandan clarifies, is to make sure the data reaches officials in real-time, along with a log of when an application was received and what has happened since. The application also has an in-built warning system designed to notify about pending applications, forcing officials to act on them. Apart from keeping track of toilet demand, Samarthan is also keen on developing a database of trained masons in the area. As of now, only Samarthan and local government officials have access to the application. Villagers cannot access any of the data and have to approach the swachhta doots to know about their application's progress.

The aim was to get the application to cut through convoluted bureaucratic red-tape and minimise the turn-around time--from submission of application to subsidy sanction. The mobile app is part of a larger picture that seeks to demystify sanitation concerns and enable the community to work in tandem with bureaucracy to bring a positive change in the lives of rural folk.

People at Samarthan could not be happier with the way things are progressing. "The district and block level officials have been very proactive and open to ideas from the start, lending more meaning to the exercise," adds Mankaj. A second pilot is currently on in 10 villages across Sehore to help correct minor tech issues and refine the system further. The analysis would then be taken to implementers at the district level to see if this could be scaled up and replicated elsewhere.

In a state where 71.2 percent of households lack sanitary latrines, this could indeed be a game changer if it were to achieve the lofty goals of the Swachh Bharat Mission by 2019.